The first time I heard Ode to Billie Joe was on a 1967 Radio 1 special. Amid ornate psychedelic pop sounding a little like Strawberry Fields Forever, this tale of suicide, loneliness and familial breakdown was unlike any record I had ever heard. The place names – Tallahatchee, Carroll County, Choctaw Ridge – were cinematic, the singer’s voice was husky, the string arrangement was minimal and eerie. What I heard was thick mud, damp moss, a barely moving river, dead air. The song was an inescapable fug. You couldn’t move. You had to listen.

Bob Stanley, writing in The Guardian, Oct 17, 2018

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2018/oct/17/bobbie-gentry-trailblazing-queen-of-country

Normally, I’m the only guy allowed to wax eloquent around here, but I came across the article linked above, and I couldn’t imagine writing anything more deftly evocative of the mood conjured by today’s selection than Bob Stanley’s almost poetic opening paragraph.

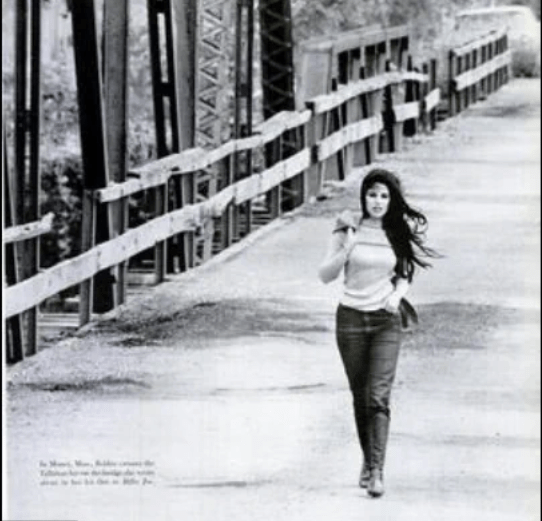

Hard to believe, but Ode to Billy Joe was Bobbie Gentry’s debut, arriving like something out of time from somebody out of nowhere. All of 23, she wrote and produced it herself, which was practically unheard of for a woman back then, without any expectation that it was going to amount to anything. In fact, it was meant to be the B-side of her first single, occupying the space where songs usually go to die, and arranger Jimmie Haskell recalls that he was given complete freedom to ignore the commercial conventions and just indulge himself when scoring the string accompaniment, “because nobody was ever going to hear it anyway”. He decided to do something different, explaining that “Bobbie’s lyrics are like a movie, so I composed the string arrangement as if it were a movie,” to which end he wrote the score for four violins and two cellos, not the typical pop music string section, and close-miked the cellos for effect.

Once they’d heard the final form of the recording, as adorned with Haskell’s strings, the higher-ups at Capitol records, to their credit, realized they’d be nuts to release it as a B-Side. The song was captivating, haunting, and refreshingly different in so many ways, not just as compared to the popular hits that had thus far defined the sound of the 1960s, but especially when juxtaposed to the stuff that was dominating the airwaves as 1967’s Summer of Love drew towards its trippy zenith. The reigning Billboard number 1 when Ode to Billy Joe found it’s way to the AM radio DJs was All You Need is Love, accompanied on the charts by all kinds of flower-powered psychedelia, songs like Whiter Shade of Pale, Light My Fire, Somebody to Love, San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair), Incense and Peppermints, and White Rabbit. The Zeitgeist album of the era was Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, released just a couple of months earlier. Now along came this almost languid, downbeat, deeply personal, utterly compelling outlier that sounded as if it might have been written by some poor sharecropper’s daughter sometime before the turn of the century (albeit an awfully talented sharecropper’s daughter). It was hard to pigeonhole, too, not exactly country, not really folk, certainly not rock (I’ve heard it described as “Southern Gothic”), and not about anything you’d expect in a hit single. Everybody else was singing about peace, love, and a dawning age of utopian co-existence, while Gentry, both feet planted firmly on the ground, was telling the sad story of a young man’s suicide down in dirt poor Mississippi, with dry, matter-of-fact authenticity, as if deliberately to draw the blinds on all that cosmic sunshine.

It begins almost like a novel, setting the scene in spare, uncomplicated language, forming a narrative that sounds so true to a certain way of life that you wonder whether maybe this isn’t just somebody’s made-up story:

It was the third of June, another sleepy, dusty Delta day

I was out choppin’ cotton, and my brother was balin’ hay

And at dinner time we stopped and walked back to the house to eat

And mama hollered out the back door, y’all, remember to wipe your feet

And then she said, I got some news this mornin’ from Choctaw Ridge

Today, Billy Joe MacAllister jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge

Kinda grabs you right away, don’t she? There you are, absorbed in the mundane details of an unremarkable day, when – wait – what? Did Mama just say, in an off-hand sort of way, that somebody they know had just thrown himself off a bridge? Why, for God’s sake? Listening for an answer amid the banal dinner table conversation, we’re drawn into a mystery, learning along the way that the narrator was Billie Joe’s girlfriend (though nobody present seems to realize it), but then, frustratingly, precious little else. There’s just that one tantalizing clue, and boy oh boy, do we ever want to know what it was that Billy Joe chucked off of that bridge before he killed himself. A lot of people thought it might have been an engagement ring, tossed because the narrator had rejected his proposal, in which case the poor kid died in a fit of romantic despair. Others felt it must have been the evidence of something more terrible, something unforgivably transgressive, even criminal, and so unspeakable that the kid couldn’t live with the guilt. All we could do was speculate, because Gentry never tells us. That’s the real genius of it. This isn’t The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia, with a big reveal at the end. The mystery lingers, and it drives us to distraction.

Over the years, before she withdrew from public life, she must have fielded the question a million times: for the love of God, woman, what did he throw off the bridge? A murder weapon? A secret journal? Yikes, a stillborn baby? Tell us! She wouldn’t, because she honestly couldn’t; Gentry didn’t know, either. She’d never developed any fixed ideas about it, it was supposed to be a mystery, the solution to which, she’d always stress, was wholly beside the point. The song isn’t really about what caused the boy’s suicide, it’s about indifference to tragedy, absence of empathy, and the passive, often unconscious forms that cruelty can take. Nobody at that dinner table cares even a whit that a tortured soul, a person they all knew, just put an end to himself, nobody but the narrator anyway. It’s just something noteworthy, is all, the kid up and jumped, isn’t that a shame, but then that boy never did have a lick o’sense, and pass the biscuits, would you? From the Songfacts article:

When Record Mirror asked Gentry in 1967 what was thrown from the bridge at the end of this song, she replied: “It’s entirely a matter of interpretation as from each individual’s viewpoint. But I’ve hoped to get across the basic indifference, the casualness, of people in moments of tragedy. Something terrible has happened, but it’s ‘pass the black-eyed peas’, or ‘y’all remember to wipe your feet.'”

You get the sense she considered this disheartening numbness to the pain of others as simply the product of immutable human nature. It’s just the way it is, you know, like it always was, it goes like it goes. People live, people die, the world keeps turning, the muddy Tallahatchie keeps flowing down towards the Mississippi River, and that’s pretty much all we can know for sure when the song winds up.

The final verse serves as a sort of anti-climax. She tells us a year’s gone by since that day that Billy Joe died. In the interim, her brother got married and moved away, her father was killed by some virus that was going around, and her mother fell into what sounds like clinical depression. She says she still makes regular visits to Choctaw Ridge, where she picks flowers to throw off the bridge in Billy Joe’s memory, suggesting that despite what sounds like the dull affect of her delivery, the suicide (and maybe her own part in whatever led to it) has left her regretful, maybe remorseful, and probably heartbroken. We can’t really tell. We aren’t ever going to find out, either, because she’s done talking. End of story. That’s literally all she wrote. No redemption, no answers, no resolution, and nothing to be done. Look, if you were hoping to tap your happy little toes to a buoyant feel-good joyfest of a tune, you should have gone and listened to something by the Beach Boys, or maybe the Monkees, somebody like that. Bobbie wasn’t here to sugar coat it for you.

Upon its release, Ode to Billy Joe knocked the Beatles down to number 2 on both the album and singles charts, with the 45 holding down the top slot for four weeks. It went on to win multiple Grammys: Best New Artist, Best Vocal Performance, Female, and Best Contemporary Female Solo Vocal Performance, as well as Best Arrangement Accompanying A Vocalist Or Instrumentalist, for Jimmie Haskell’s innovative score. 7 albums and 11 charting singles followed over the next four years, at which point Gentry, as enigmatic as her most famous song, made like Bobby Fisher and quit the recording business while she was on top. She did shows in Vegas up to 1981, and then vanished altogether. She’s barely been seen, and has never been interviewed, since.

So that’s two mysteries she’s left us.