Pre-launch, almost ready to go

Way out in space at a range of about one million miles, four times as distant as the Moon, an incredible machine sits parked in a little fixed orbit around an invisible gravitational sweet spot, from where it supplies us the best view we’ve ever had of the universe around us. Sometimes it’s tasked to look outward towards the farthest recesses of deep space, sighting objects that are billions of light years away, and sometimes it’s trained toward nearby stars, or planetary bodies much closer to home, within our own solar system. No matter the target, it expands the frontiers of human knowledge virtually every time it sends us the latest imagery.

It’s named the James Webb Space Telescope. It’s among the most sophisticated manifestations of scientific and technological prowess ever devised, and unlike most of the things that could fit that description, it wasn’t designed to kill people or blow things up. Its much nobler mission is to help us find answers to the most fundamental questions surrounding our very existence and place in the cosmos, including what, exactly, the essence of the universe really is, what it’s made of, how it evolved, and why it works in the mysterious ways it does. It may even provide evidence supporting most every astronomer’s intuition that we aren’t alone in this vast, expanding wilderness of space-time.

The Webb was launched on Christmas Day, 2021, after a protracted and painstaking process of construction and testing that wound up costing American taxpayers a whopping ten billion dollars, almost enough to buy a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier. The huge price-tag was controversial, and well over budget, but entirely commensurate to the almost unreasonably ambitious goals of the program, which sought to build something that would be to the famous Hubble Space Telescope what the Hubble was to the Earth-bound telescopes employed by its namesake. You want a quantum leap? Fine, but quantum leaps are expensive. They also take time. The finished Webb was the result of over 20 years of research, development, and construction.

But why did anyone have such a burning need for a quantum leap just now? Aren’t the images returned by the Hubble already spectacular? Well, yes, yet wonder that it remains, the Hubble is no longer state of the art. New techniques have evolved that enable us to build something a lot bigger and many times more sensitive, and you know how astronomers are: no matter how far they can see, they always want to see farther. There’s also an issue with the sort of light the Hubble was designed to perceive, which is mainly wavelengths at the high end of the spectrum, from visible light up into the ultraviolet, and only a small part of the infra-red. That’s fine, but light from the higher-wavelength blue end of the spectrum can’t penetrate the various interstellar dust clouds that often block the Hubble’s view. For that you need something that ignores higher wavelengths, and digs deep into the infrared, at the other end of the spectrum, since, for reasons I’m not equipped to explain fully, infrared light goes straight through all of that dust (the Astronomy for Dummies explanation is that light isn’t scattered by particles that are smaller than its wavelength, and the wavelength of infrared is larger than the size of most of the atoms and molecules that compose the dust and gas out there). I’ve read that the closest thing to the blue end of the spectrum detectable by the Webb is a wavelength about the colour of red wine.

Looking at the red end of the spectrum has other advantages, too. Since most every object in the universe is moving away from us – a product of the relentless expansion of the spacetime in which everything out there is embedded, which itself is a consequence of the Big Bang – the light coming at us from all points of the sky is skewed toward the lower end of the spectrum, “red-shifted”, owing to the Doppler effect. The farther an object is from us, the more red-shifted its light tends to be. It therefore makes sense to design a telescope that perceives all the light that’s too red-shifted for the Hubble to capture, especially if the goal is to observe objects at a greater distance than the Hubble can.

So, the requirement was for a telescope with a much bigger mirror than the Hubble’s, which sees much lower wavelengths than the Hubble can detect. As you can imagine, this presented a number of challenges.

Let’s begin with the mirror. To be launched within the nose cone of a rocket, the mirror can only be so big, yet what the astronomers wanted was something that compared to the Hubble’s mirror like this:

That’s an increase from 2.4 metres to 6.5 metres, and that’s far too large to fit into any rocket in the inventory.

Then there’s the need for high sensitivity to infrared light. Infrared is, put simply, the part of the spectrum that represents heat, and the best way to detect something hot is with an instrument that’s kept very, very cold. How to do that with anything that orbits the Earth, exposing itself regularly to the massive heat radiated by the Sun? Not possible! The telescope would therefore need to be somewhere much farther away, into the realm of deep space, and even at that it would need sizeable shields, oriented constantly in the Sun’s direction, to block out the light that would still reach it. Like the desired mirror, those shields would have to be much bigger than anything any available rocket could handle.

The very clever answer was to construct it so that the whole thing folded and unfolded like an origami butterfly. You might wonder how that’s feasible. Components like the shields could be made of pliable material that fit the bill, but the mirror, you might think, had to be a solid object that didn’t bend. The mirror is, after all, the whole ball game, and it has to be shaped to focus incoming light perfectly, which traditionally involved a process that’s almost inconceivably delicate and precise. Didn’t that need to be accomplished by technicians down here, on the ground, before launch? Until recently, yes, that would have been the case, but now, exploiting all sorts of technological advances achieved since the Hubble was orbited, the mirror could be divided into three large folding parts, themselves composed of smaller individual hexagonal segments, and sent up “raw” with the optics yet to be perfected. That would come later, after the telescope was fully deployed at its destination, by way of a novel method that perforce required the most crucial part of the telescope’s fine-tuning to be accomplished up there, where nobody could get to it if the process went awry. This was frightening, if you let yourself think about it too much, but it couldn’t be helped. The mirror had to fold. The calibration had to happen in space.

All folded up and ready to launch

This delicate post-launch calibration process was part curse, but part blessing too. The reader might recall that when the Hubble was first sent into orbit, its mirror, meticulously polished and calibrated on the ground before launch, turned out nevertheless to be flawed, rendering the whole expensive contraption virtually useless. A very embarrassed NASA had to launch a rescue mission using the Space Shuttle, which employed the vehicle’s articulated arm to corral the telescope – a maneuver much trickier than it sounds – so astronauts could complete a fairly dangerous space walk to go out and apply the needed adjustments, in effect giving the Hubble a corrective contact lens. It worked, but whew, that was close!

The Webb, obviously, wouldn’t have that problem, not if everything worked properly, at any rate. True, calibrating the unfolded mirror would be easier said than done, requiring the most minute manipulations of each of the hexagonal sub-mirrors in increments of nanometers – mere billionths of a metre – but this was doable with present technology. Something called a wave-front sensor (don’t ask me!) would then evaluate how light struck each of the hexagons, and calculate the incredibly tiny adjustments needed to bring them all together into a coherent whole. The sub-mirrors would then be manipulated in both curvature and position by computer-controlled actuators attached to each of their backsides, with final refinements being made by reference to the light of individual stars. Truly, the mind boggles. This is what the hexagons look like from behind:

Here’s how NASA describes the calibration:

These corrections are made through a process called wavefront sensing and control, which aligns the mirrors to within tens of nanometers. During this process, a wavefront sensor (NIRCam in this case) measured any imperfections in the alignment of the mirror segments that prevented them from acting like a single, 6.5-meter (21.3-foot) mirror. Engineers used NIRCam to take 18 out-of-focus images of a star – one from each mirror segment. The engineers then used computer algorithms to determine the overall shape of the primary mirror from those individual images, and determined how they must move the mirrors to align them.

Amazing, no? Telescope mirrors used to begin as solid discs that had to be ground down and laboriously polished into their final, optically perfect forms. This one literally bends itself into shape.

With all that worked out, there’s still another, quite basic problem: where do you put the telescope? They couldn’t just blast the thing toward any old patch of deep space, where it would need untenably massive quantities of rocket fuel to stop, and then maneuver constantly to maintain station relative to the orbiting Earth for the duration, instead of drifting away from us while Newtonian physics set a path for it (remember, up there everything is moving relative to everything else, all of the time). A free-floating Webb just wasn’t feasible. If it wasn’t going to be tethered to us in Earth-orbit, it had to be parked somewhere else where it would stay put. Where, out there in the middle of nowhere, were they supposed to find a suitable hitching post?

It sounds like a real head-scratcher, but it’s not, and here’s where you really do have to stand in awe of the requisite science, even if nothing’s impressed you so far. Just where to send the telescope had never been much of a question, because it had long since been calculated that the complex interactions of gravity fields between pairs of orbiting bodies – like, say, the Earth and the Moon – would produce a few special points at which their opposing gravitational pulls would combine, such that an object could sit there, maintaining its relative position while hitching a ride. In lay terms, the interacting orbital bodies would latch on to anything placed at one of these points, and haul it along with them through space, dragging it between them as if by an invisible string. These areas of gravitational pull are called Lagrange points, in honour of the mathematician who first worked it out. Here’s the explanation from the NASA website, if that helps:

Lagrange points are positions in space where objects sent there tend to stay put. At Lagrange points, the gravitational pull of two large masses precisely equals the centripetal force required for a small object to move with them. These points in space can be used by spacecraft to reduce fuel consumption needed to remain in position.

Better? No? Well, never mind, we don’t have to comprehend it, we just need to know that these Lagrange points exist. Here’s a chart showing the ones plotted within the Earth-Moon system:

Of the five available, the one labelled “L2” was for various reasons the best place to send the Webb.

That all sounds cut and dried then, right? All problems solved? Well, in theory, sure, but then comes the tricky part where you have to make things happen in reality like they do on paper, and getting anything as complex as an infrared space telescope with solar shields to unfold like something out of a Transformers movie is an extremely – and I do mean extremely – fraught and involved undertaking. All of the individual steps in the deployment sequence, hundreds of movements of various components both big and small, have to come off in exactly the right order, in exactly the right way, with every moving part ending up in exactly the proper position. Dozens of pins have to release, latches have to catch, telescoping rods have to extend, and so on, almost ad Infinitum. For it all to work, almost nothing can go even a little bit wrong. Here’s a computer animation, showing the complex process of unfolding that the Webb actually had to execute before it reached L2:

I mean, come on. Holy crap that’s complicated! Can you imagine betting your life savings on anything so elaborate coming off so perfectly? You’d have to be crazy to take that bet, right? Yet there they were, wagering both ten billion dollars, and their own professional reputations, that they’d worked all the angles, tested all the possibilities, and figured it all out to the highest possible degree of confidence. Sure, this was hardly the first time that NASA’s engineers had signed off on an expensive mission that involved almost harrowing multi-step, cant-fail mechanical hijinks – think of the Mars landing sequence for the Perserverence rover – but this time, from an ordinary spectator’s perspective, they seemed not just to have been courting a high-profile disaster, but positively begging for it.

Yet they weren’t, not at all. Don’t be silly! These guys know what they’re doing! Repeated dry runs on the ground had exposed the glitches – for example, in one test, the solar shields had torn – and they’d all been ironed out. Their methodology was precise, meticulous, and exhaustive, and they were completely comfortable that all but an irreducible minimum of risk had been removed from the equation. They had to be, else they’d never have launched the thing.

You and I can’t really understand how arduous it was to attain that comfort level.

I’m thinking it must still have been a little bit nerve-wracking, watching helplessly as the successive steps were completed, one after the other, at a necessarily painstaking, glacial pace. How glacial? Well, the attached video is a time-lapsed presentation of a process that took just short of two whole weeks to complete, everything moving ever so slowly and deliberately, in a sequence which, the engineers reckoned, contained 344 so-called single point failures. Put simply, this meant there were 344 times when the merest deviation from perfection would have thrown a spanner in the works, at which point the whole thing would have gone irretrievably wrong, and the Webb would have been reduced to a ten billion dollar pile of derelict space junk.

Now, I would have told them, just on general principles, that 344 single points of failure were about 339 too many for anybody sane to contemplate, and it was therefore time for a major rethink. See? What do I know? It came off without a hitch.

After that it took a few months to complete all the tests and calibrations, time that was also needed for the mirror to cool down sufficiently to begin gathering in infrared light, and it wasn’t until July, 2022 that NASA released the first pictures. What pictures they were, too, fabulous, mind-blowing images, some showing things we’ve observed before, but now in unprecedented detail, some revealing things we’d never even dreamed existed. It wasn’t long before headlines with a common theme were appearing in the popular science press:

It wasn’t hype. The astronomers could hardly believe their eyes. They’d never had it so good, as the Webb actually exceeded expectations and returned imagery at a higher resolution than hoped for by even the biggest optimists. Look at this:

That’s Titan, the giant moon of Saturn, and the only place in the solar system other than our own planet to boast stable liquid oceans on its surface, composed not of water, but methane. The white fuzzy areas are clouds, presumably made of methane too (I’m guessing). How about this:

That’s Neptune, seen more clearly than at any time since the Voyager 2 flyby in 1989. The distant planet’s ring system is clearly visible in the infrared spectrum. Look at this:

These are what came to be known the Pillars of Creation, after being photographed quite famously by the Hubble, now pictured with a penetrating clarity that was previously impossible. The Pillars are “stellar nurseries” about 7,000 light years away in the Eagle Nebula, gigantic columns of dust and gas that stretch for about five light years, within which new stars are being formed. Because the Webb sees through the dust, we can spot proto-stars in the midst of their gestation.

This is the Webb’s first “deep field” shot:

This multitude of stars and distant galaxies is contained within a tiny speck of the telescope’s field of view, an area about the apparent size of a grain of sand held at arm’s length. The objects that seem blurry aren’t out of focus; they’re far away, and their light is being distorted by “gravitational lenses” as they pass through the bends in space-time imposed by the gravity of other, nearer galaxies.

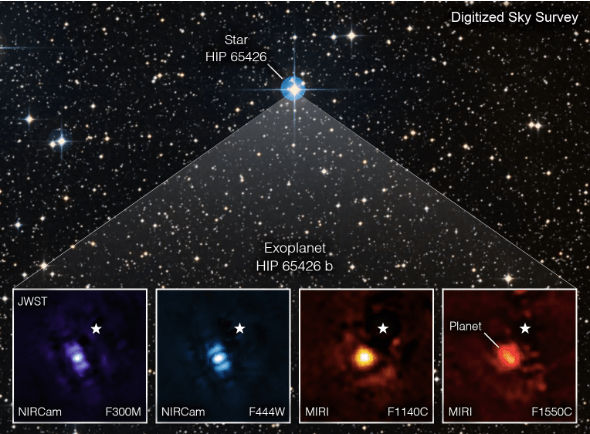

The Webb’s vision is so acute, it can even discern individual planets orbiting distant stars, and gather enough information about them to make spectrographic analyses of their atmospheres. This is object HIP 65426b, a young planet ten times the size of Jupiter orbiting a star that dwarfs our own Sun, roughly 400 light years distant:

It wasn’t that long ago that planets outside our solar system, referred to by astronomers as “exoplanets”, were only a theoretical possibility, but now we’ve catalogued thousands, lately by using subtle techniques to separate their faint spectral signatures from the blinding backlight of their parent stars. This has only become possible quite recently. Early on, detection was accomplished mainly by inference, by measuring the tiny reductions in radiated starlight as a planet crossed its parent star’s face, or the gravitational wobbles that planets induce upon the stars they orbit. Taking direct images of the planets themselves is a whole other order of achievement. Contrary to some press reports, the Webb wasn’t the first to manage the feat – Earth-bound telescopes have done it too, as far back as 2004 – but it’s never been done like this. By examining the long-wave infrared light that our own atmosphere screens from telescopes on the ground, the Webb gathers in unprecedented information about the atmospheres of exoplanets by examining the wavelengths of light that get absorbed from the starlight shining through them. This allows astronomers to identify the gasses, if any, which either surround or wholly-compose the planets under study. The reason this gets them all so terribly excited is that it allows us to tell whether an atmosphere is Earth-like, and suitable for life. A major part of the Webb’s mission is the identification of such planets, around which we might one day identify the gaseous fingerprints of living things, what they call “biosignatures”, and determine, finally, that we aren’t all alone in the universe.

Perhaps even more impressive than how well the Webb sees things is how incredibly far away those things can be. Peering off into the almost infinite distance, it’s gathering images of galaxies that are almost 13.5 billion light years distant, a figure that’s practically meaningless in its enormity. How to put that into some sort of perspective? Perhaps a good way to start is to understand the breadth of a single light year (which is not a measurement of time, but of the distance that light, travelling at 186,000 miles per second, will travel in an entire year). This is about six trillion miles. Six thousand billion miles for just one light year. The nearest star to our own is about 4.5 light years away, meaning that upwards of 27 trillion miles is right next door in astronomical terms. Our own Milky Way galaxy spans about 100,000 light years (or perhaps as many as 200,000 based on the latest research), and the nearest comparable galaxy, Andromeda, is over 2.5 million light years away. That’s an awfully long way, already approaching too many millions of trillions of miles to properly comprehend. Yet the galaxies that the Webb is detecting are 5,400 times as distant.

Something else to blow our tiny minds: it follows that the most distant light the Webb can detect has travelled for 13.5 billion years to get to us. The universe, we reckon, is about 13.8 billion years old. So the Webb is observing light emitted only about 300 million years after the Big Bang, when the universe was in its infancy, meaning we’re seeing back virtually to the beginning of time itself, and therefore almost to the limit that any subsequent, better telescope we might build will ever see. We know there are objects far more distant than that – after the Big Bang, the universe went through a period of extremely rapid inflation, following which ongoing expansion has probably enlarged space-time to a breadth of something like 94 billion light years (!!) – but no matter what we do, we’ll never see them. We’ll never be able to see back to beyond the beginning of time, and meanwhile, the accelerating expansion of the universe is causing all the light emitted by those distant, invisible objects to run away from us at a growing rate measured, currently, at about 1.4 light years per annum. Every year, then, more space is being put between us than light can travel. Even if our species is still here a billion years from now, we won’t be able to discern much more than the Webb already can. The very same galaxies will just be farther away, and receding inexorably from view.

It’s an amazing thing to contemplate. We’ll never see to the edge of space. But with the Webb, we’re seeing right to the very edge of time.

What could be more awe-inspiring than that?

Awe-struck. That’s the feeling every time I look at a picture of this latest product of our genius. It seems fitting, I think, that the device designed to realize so many grand aspirations most certainly looks the part, with its great array of shimmering gold hexagons, and solar shielding looking like the sails of some sort of space-faring super-yacht. It’s really quite beautiful, though of course this is only a happy accident of form following function, and doesn’t matter in the slightest, either to how it works, or to how much it impresses. It could have turned out as homely as a dump truck, and it would still be utterly awesome in its sheer, gob-smacking, Swiss-watch-surpassing precision. The ingenuity and mechanical elegance of the Webb’s fantastic design is almost literally breathtaking, as is an appreciation of the depth of knowledge required to build it and put it where it is, doing what it does beyond all expectations.

For me, it’s a symbol of hope, evidence that no matter how bad things look, there’s still something to be said for our troubled civilization. Not everything’s corruption, lies, greed, and cruelty, not quite. You and I may be stranded down here, sick and depressed at being mired in so much of what reeks of humanity’s worst tendencies, but it helps to remember that somewhere up there, far beyond anywhere any human being has ever gone, one of the highest expressions of our most admirable qualities is going about its unsordid business, doing its part to feed our insatiable hunger to understand. These days, more than ever before it seems, it’s the morons, A-holes, liars, and outright grifters that clog the public square, but there are those, working quietly off to the side, who still reach for the stars.

It’s a thought that I find comforting. I guess I’m writing this because I hope you will too.

Just imagine the wonders sure to be revealed as the telescope does its work over the next few years, and think of all the apple carts that are going to be overturned as longstanding theories are tested against observation. It’s already happening. The most distant galaxies being detected are much younger than we’d thought possible. We didn’t expect there to be any fully-formed galaxies at all when the universe was only 300 million years old. Back to the drawing board, as it were, for the first of what are likely to be hundreds of times, as we push closer and closer to the answers we’ve sought since the first of our hominid ancestors looked up wonderingly at the stars. Still to be solved are the mysteries of dark matter, dark energy, and a few other riddles beyond the scope of today’s essay. If we can ever get to the bottom of such things, the Webb is sure to be involved.

Meanwhile, the quest for extraterrestrial life will continue. This amazing telescope, surveying almost all of the visible universe from its perch beyond the Moon, might just find it. It’s even conceivable, without letting the imagination run too far afield, that the Webb will spot something that indicates the presence of intelligent life. Maybe somebody out there is pulsing out signals in the infrared spectrum, perhaps using lasers. Maybe an alien race has placed something in space so enormous that we can see it from here, like a Dyson sphere.** Maybe substances detected in some planet’s atmosphere will support the inference that some sort of industrial activity, and not just the respiration of living things, must be going on. Nothing of the sort is at all likely, but it’s a very big universe, and the probability isn’t zero.

I wonder, what then?