Imagine viewing, within the span of about a year and a half, films as diverse and stimulating as Badlands, Dr. Strangelove, Alien, Blade Runner, Road Warrior, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Thief, The Searchers, Body Heat, Being There, The Third Man, The Conversation, Paths of Glory, Cutter’s Way, Satyricon, Gallipoli, Breaker Morant, The Year of Living Dangerously, and Blow Up, most projected onto enormous screens, as I did during my time as a wide-eyed undergraduate at Dalhousie University. A lot of them were shown on campus, at the Rebecca Cohn Auditorium, a terrific concert venue that was maybe the best place I’ve ever been to watch a movie, and others were playing in the first of the Dolby-equipped theatres then popping up, which were able to project 70mm prints in glorious stereo. It was wonderful. I’ll never again see so many mind-expanding movies, presented so well, in so short a time.

It was around the same time, in one of the recently-upgraded downtown theatres, that I first saw Apocalypse Now. My studies had already steeped me in the details of the then-recent war in South East Asia, and I was keen to see what the director of the Godfather movies had made of it all. I didn’t approach the thing with any sort of emotional reservation. I was happy as a clam as the lights went down, equipped, I’m sure, with a nice big super-extra-large tub of oily popcorn, and a half-gallon of extra-sugary Coca-Cola.

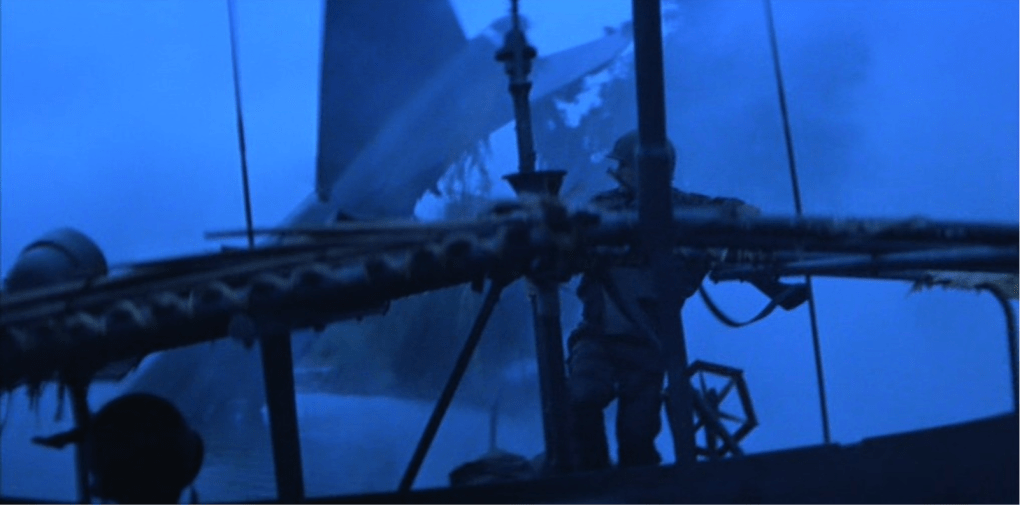

After about a minute, I probably stopped chewing and let the big plastic straw slip from between my teeth, already thoroughly mesmerized and motionless. From the very beginning, it was like descending into some scarred veteran’s drug and PTSD-addled fever dream, immersive, compelling, and demanding of your undivided attention. Right from the get-go. Dazzling. It didn’t let up, either. I was pretty much overwhelmed when, a couple of hours later, I shuffled out of the theatre in a bit of a daze, while dozens of unforgettable images and set-pieces replayed over and over in my mind, as they would ever after: the famous helicopter assault; the surreal USO show, with the Playboy Bunnies and the band playing Suzie-Q; the even more surreal nighttime chaos at the Do Lung bridge; Kurtz’s nightmarish compound; Kurtz’s pre-ordained assassination, juxtaposed with a ritual animal sacrifice; the many scenes on the patrol boat as it headed up river, carrying Willard to his destiny; the frightening attack on that boat from unseen enemies on the shore; the catastrophic inspection of the local watercraft on suspicion of smuggling arms to the VC; the foray into the jungle to find a mango tree; there were just so many. I was particularly haunted by the vignette of Willard and the boys gliding beneath the dismembered tail section of a B-52, sticking out of the jungle mud like a lawn dart.

None of it ever leaves you.

The dramatic impact of course owed much to the cinematography, which remains among the finest ever achieved, but just as much to the soundstage conjured out of all those fancy new speakers, which was often almost literally breathtaking. To this day, I don’t think anybody’s made a movie with sound like Apocalypse Now, and it was the sound, actually, that first grabbed you, right at the opening, as you looked at the initially silent establishing shot of an unremarkable jungle scape, waiting for what comes next. There’s nothing much going on, just yellow dust billowing ominously, except there’s a strange sound, this odd sort of phhhyt phhyyt phhhyt noise moving across the stereo soundstage.

That’s when I must have stopped grazing in my popcorn tub. There’s no other sound quite like it, it’s unfamiliar, distorted, foreboding, even evil, like the sound of knives cutting flesh, and fit to stop you in your tracks like a frightened little rodent sensing an owl. As helicopters come into the shot and cross paths in the foreground, The Doors fade in, Jim Morrison singing The End, and something – maybe the choppers, but maybe something a great deal more destructive – lays utter waste to the entire jungle. Napalm. If you knew anything about the war, you knew that was napalm, an ugly, horrifying weapon. The musical accompaniment is eerie and uncannily appropriate, Morrison droning wilderness of pain, and all the children are insane, before the Vietnam War’s most ubiquitous sound, unmistakeable to anyone who’s ever heard it even once, takes over the stereo image. It’s the percussive thump-thump-thump of the Huey, the troop-carrying part-time gunship helicopter that filled the skies over ‘Nam by the thousand, emitting what author Michael Herr described in Dispatches, his superb account of his time as a reporter working in-country during the war, as “the only sound I ever heard that’s both sharp and flat at the same time”. Herr also wrote the narration for the movie, Captain Willard’s internal monologue, and if you’ve ever read Dispatches – and you should – you’ll understand why Herr was the obvious choice, and probably the only one that Coppola considered.

By this point, believe me, nobody was taking a washroom break or wandering off to rustle up more grub in the lobby. You’ll never experience a more effective matching of soundtrack to imagery. It really is extraordinary.

I remember feeling a sort of dread when being introduced to poor, frazzled, drunken Captain Willard, who’s having a nervous breakdown in his claustrophobic little Saigon flat (which mental collapse looks authentic because Martin Sheen really was having a nervous breakdown, really did lacerate his hand by punching a full-length mirror, and really did weep inconsolably, filled with genuine despair and pouring himself full of whiskey, while Coppola figured what the hell, he might as well film it). Apart from the obvious, what’s most striking is the use of overlaid multiple exposures, some of which present foreshadowing imagery that the viewer hasn’t yet seen enough to comprehend. It’s fascinating, confusing, and altogether masterful; we see Willard’s face in closeup, the burning jungle, helicopters, always helicopters, some strange stone statuary, and a brief glimpse of Willard himself moving furtively, with death in his eyes, among that same stonework, all of it mingling on screen, and we aren’t sure what the hell is happening. We just know it’s not going to be good.

Clearly, Willard does too. Saigon, he says in something close to a sigh, as he drags himself to the window, looking out to remind himself where he is. Shhhhhhhit. I’m still only in Saigon. You see, every time he wakes up, he expects to be back in the jungle. Wants to be back in the jungle, he seems to imply. When he says that, you already feel like you understand a little of what he’s been through, and a bit about what’s yet to come.

Apocalypse Now was based on Heart of Darkness, a short story by Conrad, and it’s full of allegory, motifs from ancient myth, and symbolism both overt and subtle. You can’t possibly absorb it all properly in just one viewing, so, rising to the challenge, my younger self went to see it 22 times over the year or so following its release. Yup, I kept track, it was 22 times projected, (no home video back then), and it took almost all of those screenings for me to finally understand the film’s central message, a lesson which remains sorrowfully unlearned by the architects of U.S. foreign policy. Somebody should render it in stone, and hang it over the main entrances of the Pentagon, the State Department, and wherever else the ideologues of America’s hawkish and unaccountable think-tanks call the shots: Never get off the boat. Not unless you’re going all the way.