The Only Band That Matters. That was their billing, and you know what, for a while there they really were. Emerging out of the mid-1970s Punk scene in what was then a very dilapidated, run-down, and not at all merrie olde England, the Clash was initially perceived as a second coming of the Sex Pistols, and they were certainly as loud, energetic, and pissed off as Johnny Rotten and friends pretended to be. This was, however, a complete misperception, still shared today by too many in the music press.

They may have looked the part, in their leather and torn clothing, and they may even have conceived of themselves as such, but the Clash was not really a Punk band. Its members, led by the great Joe Strummer, lacked all the quintessential attributes of actual punks. For one thing, they were hugely talented musicians, and excellent songwriters. For another, they weren’t nihilists, raging against everything and nothing in particular while screaming “no future”. The Clash cared. They were passionate about social injustice. They were, in fact, latter day protest singers in the finest tradition of Woodie Guthrie, hoping to make a difference. There was a future, and they’d have been damned before they let it unfold without doing anything to make it any better than the miserable present. Punks? You wish. The defenders of the status quo could laugh off the performative antics of the punk crowd; the Clash was another thing entirely, and downright scary. These guys were deadly serious, and had serious things to say.

They also rocked hard enough to make the Pistols look like weak-kneed little posers, and Led Zeppelin sound like a lounge act. If you ever require a shot of adrenaline powerful enough to restart somebody’s heart, or for some reason need to blow all the windows out of your house, just turn it up and play Safe European Home, or Guns on the Roof, but here’s the thing: those songs, as always, actually mean something. All you had to do was listen to the words.

Well, all you had to do was listen to the words if you could possibly make them out. Between the accents, the sometimes unfamiliar slang, the intonation, and the general sonic onslaught, the Clash was often notoriously difficult to comprehend. One edition of the Rolling Stone Record Guide quipped that “they’re rumoured to have terrific lyrics, but you’ll never know”, which wasn’t far off, especially for North American listeners. It was certainly true for me, particularly when it came to today’s selection, which I adored from the very first listen and played hundreds upon hundreds of times over many subsequent years without gathering more than a general sense of what it was saying.

One day, the internet age having dawned, I decided to look it up.

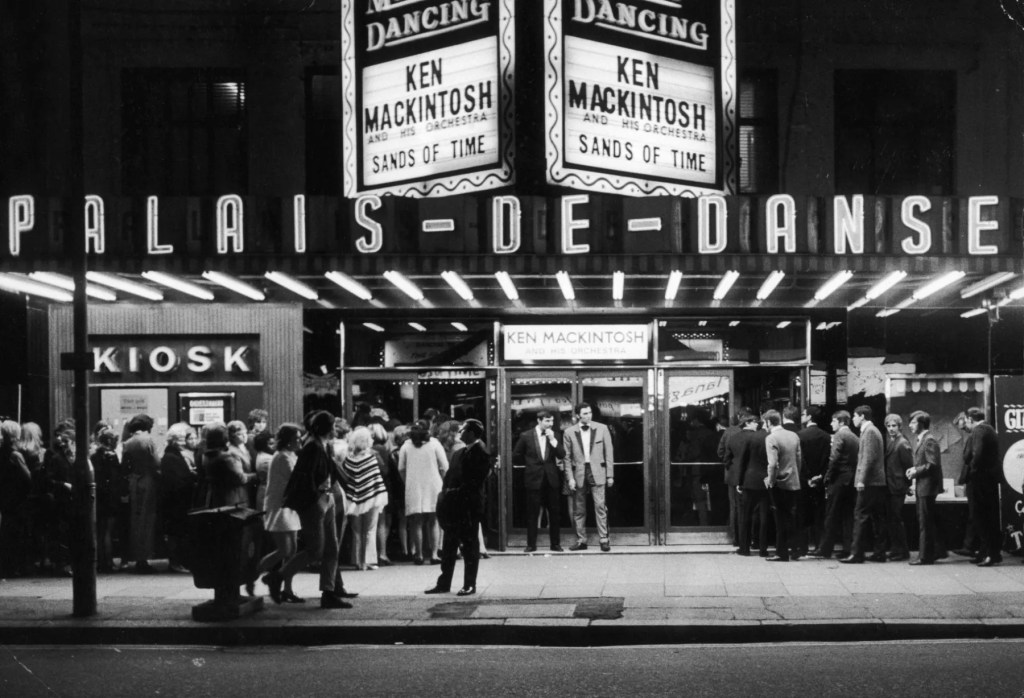

White Man in Hammersmith Palais uses Joe Strummer’s attendance at an all-night reggae music festival, which he found both disappointing and discomfiting – he was pretty much the only white person there, and was made to endure all sorts of taunts and threats on that account – as a way into commenting on the toxicity of contemporary race relations, rank socio-economic inequality, the mock counter-cultural hijinks of rival bands that were really only in it for the cash (hunh – they think it’s funny / turning rebellion into money ), and the nasty right wing politics that promised to push the whole mess to its boiling point. Why not phone up Robin Hood, and ask him for some wealth distribution? he sings, before claiming that if Adolph Hitler flew in tonight, the folks in charge would send a limo to pick him up. It was, all things considered, a total f’ing shit show out there. White and black youth had to work together, and find a better solution, which, for those grasping for easy answers, didn’t involve violence and playing with guns. Down that road lay nothing but the Riot Act and martial law, ultimately, and if the rabble rousers thought they could take on the frigging Army, they needed to think again. Maybe Joe understood why the aggrieved would feel that was too damned bad, but it was what it was.

Not exactly Pretty Vacant, is it?

Structurally, harmonically, rhythmically, White Man in Hammersmith Palais showcased a much higher level of compositional ambition than, say, a rouser like White Riot, and was essentially reggae, just like the stuff played at the concert that night, an art form with political undertones that not a lot of white bands had the nerve to take on at the time. Strummer was nervous about how the fans would respond to it. “We weren’t supposed to do something like that”, he said later, “we were a big fat riff group, like, rock solid beats”. He needn’t have worried. Fans loved it, people who’d never before listened to the Clash began buying their records, and in retrospect Strummer reckoned, rightly I think, that it was the best thing he’d ever done. My own inconsequential opinion is that it’s one of the most important songs of the last 50 years, intense, complex, passionate, full of meaning, played and sung to a level rarely achieved by anybody, and in its way on a par with the best work of the Stones, the Velvet Underground, The Who, and other such giants of the golden musical era that preceded them. I’ve certainly heard nothing since that’s anywhere near so stirring, outside, perhaps, of some of U2’s best stuff. Admittedly, at first blush it’s not for everyone, and might even seem grating and unlistenable to those who don’t like it loud and hard, but I’d urge any reluctant listener to give the song a chance. It’s not just loud, and it’s not merely angry. It’s emotional, as befits a really rather thoughtful and heartfelt commentary on so many emotional topics.

The song begins and ends with the goings-on during and after the all-night concert, at which Strummer was hoping the performers would have something meaningful to say to the “many black ears there to listen” – he was expecting the sort of protest and social commentary he was himself so eager to put to music – but instead it was all innocuous entertainment with dance choreography, “Four Tops all night” as he puts it, and thus, to him, a lamentable waste of time and opportunity. Taken aback by the hostility of an audience that was none too pleased to have a skinny, pasty white guy in its midst, he made his nervous way home through what was apparently a pretty tough neighbourhood, feeling menaced, and way too Caucasian – by some accounts he also tried to intervene to help a couple of equally out-of-their-element white girls from getting their purses snatched – while wondering, perhaps, whether his vision of greater racial harmony was nothing but a pipe dream. There sure wasn’t a hell of a lot of brotherly love in evidence that night in Shepherds Bush, and it clearly wasn’t the time to preach peace, love, and understanding. At that point, Strummer was happy just to get home without somebody beating the crap out of him. Thus the final verse:

I’m the white man in the Palais

Just a’lookin’ for fun

Only lookin’ for fun

Oh, please mister

Just leave me alone

See what I mean? These aren’t the sentiments of some rowdy punk. Joe wasn’t any sort of street-fighting man, and he wasn’t looking for trouble. He’d only come out to have a little fun, and now just wanted to be left alone while he made haste to get himself out of harm’s way. With any luck, there’d be plenty of time later on to resume the struggle for truth and justice.

Joe Strummer, sadly, died in 2002, aged only 50, not from drugs, alcohol, or any of the misadventures or self-abuse typically associated with rock stars, but of an undiagnosed congenital heart defect. The song of which he was most proud was played at his funeral. The legendary Hammersmith Palais de Danse, a venue that had hosted everybody who was anybody in its day, the Beatles, the Stones, the Who, David Bowie, the Police, Elvis Costello, you name it, a stream of each era’s most popular artists stretching all the way back to the 1920s, was shuttered in 2007, and finally demolished in 2012.