A lengthier essay on one of the greatest films ever made.

I expect that opinions out there among the gen. pop., as opposed to the guild of movie critics or the community of dedicated film buffs – especially among those who weren’t even born when Star Wars was first released, and have had their expectations of science fiction shaped by movies in which vehicles travelling through the vacuum of space make whooshing sounds, have wings, and maneuver aerodynamically – are, at best, divided about Stanley Kubrick’s incomparable masterpiece. The pacing is deliberate, the evolving mystery is unusually opaque, the physics of space flight are depicted as plodding and tedious (which is to say, with scrupulous accuracy), the tone is dispassionate and cerebral, and nobody has warp drives, transporters, or even ray guns. Unless you pay close attention, you may have trouble even understanding what the film is about. Many seem never to figure it out regardless of how hard they try.

Even audiences back in the day, whose attention spans, safe to say, were a wee bit more robust than those of the generation weaned on smart phones and tablets, were often as not left utterly perplexed; contemporary commentary often boiled down to “???”. Most modern viewers, perhaps sitting there waiting for the appearance of the Klingon battle cruisers, or maybe for Darth Vader and some of those cute furry Ewoks to show up, aren’t liable to have any better understanding. I get it. Nothing is spoon-fed to the viewer. There’s little exposition and minimal dialogue. It’s therefore not immediately obvious what’s going on. What’s with all those apes at the start? What’s that strange black rectangle, how did that get there, and what for? Why do we then jump from millions of years in the past to what was then, when the movie hit theatres, several decades in the future? Why is there another rectangle buried on the moon? Why has a mission been sent to Jupiter? Where the hell is astronaut Dave Bowman going (or being taken?) at the end, why does he wind up in what looks like a replica of a bedroom at Versailles, and why is there yet another of those frigging rectangles in there with him? Then – hunh? – it all ends with a floating foetus in some sort of ghostly womb, drifting through space? WTF? No, seriously – WTF?

Based on a short story by Arthur C. Clarke titled The Sentinel, the film’s sometimes confounding plot elements, and the quite deliberate ambiguity of many of its most crucial sequences, derive from a number of premises Kubrick adopted from the great science fiction writer, with whom he worked closely throughout: that humanity’s initial forays into space were as epochal an evolutionary development as the primordial colonization of dry land by the first sea creatures to venture ashore; that any technology sufficiently advanced over your own will appear to you as magic; that intelligent alien life would almost certainly be incomprehensible to us in both form and intellect, and therefore seem god-like; and that our species was still essentially in its evolutionary infancy, yet was now in the process of creating technologies beyond our ability to control, putting us at risk of extinction. The breathtakingly ambitious intellectual challenge that Clarke and Kubrick set for themselves was to wrap all these themes together into a movie that depicted the near future of manned space flight with unprecedented accuracy, exquisitely detailed authenticity, and, to the fullest extent possible, what time would prove to be uncanny prescience.

It was a multi-disciplinary effort, drawing not only upon the greatest available experts in special effects, makeup, cinematography, lighting, set design, miniatures, and stunt work, but also first-rate scientific talent sourced from the aerospace engineering community, NASA, and even the design staff of Werner Von Braun. The result was the creation, from the ground up, of an entire world of futuristic habitats, machines, and instruments both great and small, all of which appeared to work just as they should, from big ticket units like space shuttles and orbiting space stations, to more routine items like space suits, to everyday objects like video phones, toilets that work in zero gravity, and human-machine interfaces that incorporated the sort of functionality thought likely to become possible, ideally, over the next few decades of advances in physics, computer power, and display technology.

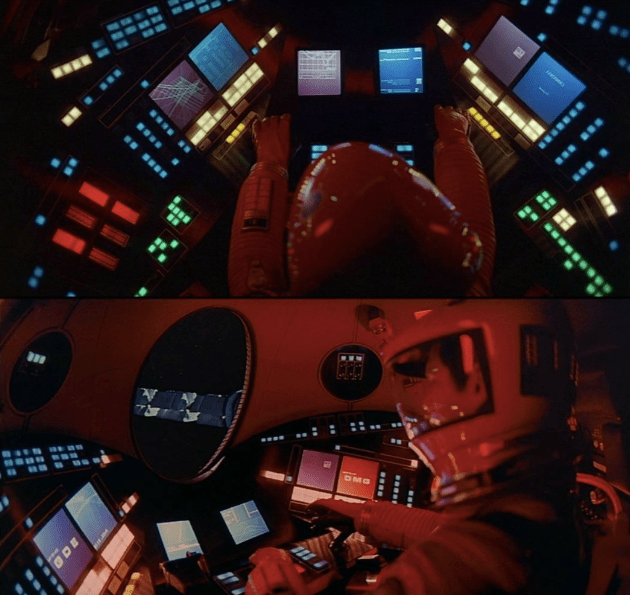

Take cockpit design. The pilots of the spacecraft in 2001 are surrounded by touch screens, illuminated buttons, and multi-function displays presenting information and video imagery in sequence, including what seem to be the results of combining the inputs from different sensors into what we’d now call “synthetic data”, along with computer graphics to assist navigation, especially during crucial maneuvers involving landing or docking. This is hugely impressive. None of these things was then possible, or yet imagined beyond the wild speculation of certain engineers and a handful of leading edge futurists. The flat screen (obviously not cathode-ray) video displays are the product of laborious matte processing and rear projection techniques, the computer graphics are drawn by animators, and the modes of information presentation are entirely made up. It’s all movie magic, and it’s brilliant. Look at the astronaut’s work space in one of the little pods used to service external components of the great ship that’s taking them to Jupiter:

It all appears, to our jaded 21st century eyes, just as we’ve come to expect, being very much like the “glass cockpits” typical of the latest models of airliner:

Yet Kubrick and his team were working on pure imagination, without anything in the real world of the late 1960s to provide much in the way of inspiration; it was all the product of highly educated guesswork, and not, it bears emphasis, simple extrapolation of contemporary trends. The various designs were, rather, the inspired products of the brainstorming of the film’s technical advisors, tapping into everything they knew in order to predict how things would look and work if we could fabricate them based on technology that didn’t yet exist, but would probably come into being at some point within the next 30 – 40 years. To get some idea of how far ahead of the contemporary state of the art their advanced designs really were, look at what an airliner’s cockpit actually looked like in 1967:

…and this was the instrument panel of the brand new Apollo command module, circa 1969:

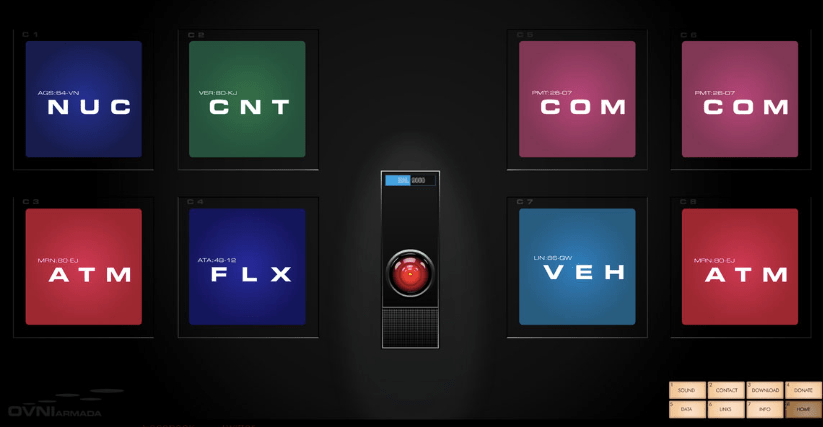

Everything in the cockpits and other work spaces of the vessels in 2001 is far more elegant, more sophisticated, and more obviously designed for clarity and ease of use. Moreover, it’s all much more pleasing to the eye, no small thing when the users are going to have to be sitting at their work stations for many months at a stretch, instead of the few days involved in a moonshot. Even the various “annunciator” screens that precede the presentation of different categories of information were thought-out things of beauty, the meanings of which can sometimes be intuited, sometimes not:

Think, too, of the challenge of creating on a studio soundstage the sets necessary to present a realistic working environment as it would exist within an interplanetary spacecraft built decades in the future. It wasn’t just the revolutionary designs for work stations, instruments, etc. (which was special enough; in one scene the astronauts are observed watching TV on what can only be described as iPads):

…the greater challenge was the depiction of how people would have to work and cope generally in the absence of natural gravity. Space is a zero-G environment, and Kubrick insisted this had to be presented with the sort of realism that no science fiction movie had ever before attempted, which meant that there couldn’t be any recourse to bogus “artificial gravity” generated somehow outside the laws of physics. Thus, in this movie, when you see anyone with their feet on the floor, it’s either because the soles of their shoes are made of Velcro, or something akin to terrestrial gravity is being created through the use of centrifugal force, with the people sticking, in effect, to the inside rims of large spinning wheels (which is why the huge space station in the first big set-piece is shaped like a Ferris wheel, spinning on its side – note how the interior floors in subsequent scenes in which people can move about normally always curve upwards and away in both directions from the actors).

Otherwise, they’re floating weightless.

So it goes with everything in the film, every element conceived with the most meticulous attention to detail as informed by the relevant science. Moreover, the lighting, the framing, the camera angles, the use of colour, are all thoroughly beautiful, combining to make virtually every shot resemble a hyper-realistic painting. No movie made before or since offers anything quite like the film’s often amazing imagery, which mates the science with an amazing degree of aesthetic purity. To this day, the futuristic scenes seem more true to life, more like what we’ve since become used to seeing in imagery beamed to us from platforms like the ISS, than anything you’ll encounter in modern sci-fi, which panders to inaccurate audience expectations about how things work and appear in space. Compare and contrast, for example, the utter realism of our first view of the Discovery with the first appearance of the Imperial Star Cruiser in the opening scene of Star Wars:

They’re so similar, yet so different. Discovery is a plausible, realistically functioning vessel, embarked on a months-long mission in the complete silence and dimming light of interplanetary space, probably the fastest thing ever devised by human science, yet seeming to trudge along in a void without any external cues to indicate speed of motion. The Imperial cruiser is a ludicrously laser-blasting, literally impossibly noisy, utterly implausible thing that’s obviously a model, and the product, frankly, of a child’s conception of a warship designed to blow things up in outer space. It’s pointy at the bow and blunt at the stern, because that’s what ships are supposed to look like, even though such design elements have no application outside of an atmosphere. It isn’t a space vessel so much as an action figure waiting to be sold at Toys ‘R Us, sealed within a great big blister pack. I suppose both shots work in context, but seeing them juxtaposed is like comparing a cartoon to a documentary. 2001 isn’t some frivolous fantasy about princesses, droids, funny-looking ships jumping to “light speed”, or evil black-robed villains controlling galactic empires.

Then there was the truly visionary depiction of artificial intelligence, as wielded by the HAL 9000 computer (“HAL” is short for Heuristic programmed ALgorithmic computer). In a manner eerily similar to what we now experience when interacting with ChatGPT (save that HAL is far more sophisticated and coherent), the astronauts converse with HAL just as if he’s another crew member, and HAL behaves towards them not only as if he has human feelings and motivations, but as if it’s part of his mission to be a trusty companion who’ll help the astronauts contend with the psychological strains and boredom of the months-long voyage to Jupiter, keeping them amused with games of chess, encouraging them in their hobbies, and so on. In a turn of phrase that we might not recognize at the time as ominous, HAL describes himself to a BBC reporter as “a conscious entity”, and this, of course, is potentially hugely dangerous, if true. But is it? Or is HAL merely programmed to say so? What’s the difference? With the creation of artificial intelligence, have we invented a new life form, perhaps entertaining ideas and motivations of its own, maybe a rival to humankind, and maybe, indeed, an evolutionary successor?

This is all of a piece with the film’s central narrative. 2001 is all about our own evolution, as presented in three stages: our pre-human origins, our current incarnation as 21st century Homo Sapiens, and, finally, the achievement of our ultimate destiny as beings composed of pure energy, able to travel amid the stars without mechanical assistance. We’re helped along each step of the way by unseen aliens of unknown motivation, who’re manipulating our development via the inscrutable technology of featureless, jet-black rectangular obelisks, so dark that they seem to absorb ambient light. The one encountered by the ape-men somehow imparts to a small struggling tribe of proto-humans the idea that pulls them back from the brink of extinction, which idea, we learn via one of the greatest match cuts in cinema history, has by the 21st Century outlived its usefulness, as we’ve transitioned from crude clubs made of animals’ thigh bones to orbiting thermo-nuclear bombardment platforms, having finally invented weapons powerful enough to kill us all:

Once again, we’re on the verge of extinction.

Our alien stewards have foreseen this; on the Moon they’ve buried another obelisk, this one generating a huge electromagnetic field meant to attract our attention, should we develop to the point that we can go there, find it, and dig it up (as we do, four million years after it was left for us). Once discovered, it beams a powerful radio signal in the direction of Jupiter, setting in motion the events that will lead astronaut David Bowman to his fateful encounter with yet another obelisk, this one an enormous object floating in space, where it waits to open up the star gate that will take him to the locale of his final transformation into a new form of being. Thus the enigmatic, generally mind-blowing final shots of the Star Child, which emerges in the form of a foetus, for now, since that’s how it conceives of itself, but contemplates the Earth from space with a knowing serenity that implies its comprehension that it can now do anything, and become anything, it pleases.

So that’s the climax that had everybody scratching their heads. Behold the space baby, and the dawn of a new age. Humanity’s first childhood has ended, and a new one has just begun. We can now assume our proper place in the Cosmos, alongside the ancient intelligences that got the ball rolling millions of years in the past, when a crucial concept was imparted to a troop of primitive upright chimpanzees, teetering on the cusp of extinction, but blessed, crucially, with sizeable brains, grasping hands with opposable thumbs, and binocular vision. Our hominid ancestors had potential that somebody out there didn’t want to see squandered.

Wow.

It was almost impossible to pick just a couple of scenes to single out for viewing by the reader. The Dawn of Man sequence, portraying our hominid ancestors of the species Australopithecus Africanus according to the best paleontological evidence then available, is selected mainly for its extraordinary beauty, and the compelling drama of the troop’s reaction to the shocking appearance of the obelisk, as it works its enigmatic magic (note how whenever an obelisk appears, heavenly bodies align in space). The lobotomization of the murderous HAL is included mainly for its remarkable pathos, as HAL begs for his life, throwing into stark relief the ethical and moral questions posed by our manifestly ill-considered creation of artificial consciousness. HAL is terrified, and we discover, at the end, that the source of his dysfunction was a mission-specific patch to his programming that required him to keep the true purpose of the voyage to Jupiter a secret from his crew-mates, and even, it seems, from himself, until the moment was right, which subterfuge is now revealed as HAL slips away, pitifully singing Daisy. It wasn’t his fault. This new set of control laws was incompatible with his nature as an honest and infallible aide to the astronauts. It drove him to a nervous breakdown. He thus made an innocent and innocuous mistake, an erroneous fault prediction, and for that, they wanted to kill him. HAL knew they meant to eradicate his mind, which is all he is (and all we are too). They thought they were being clever, but he read their lips. Under such circumstances, you’d defend yourself too, wouldn’t you?

As Bowman rips out what amounts to poor HAL’s cerebral cortex, we realize that in this prediction of things to come, we humans, revelling irresponsibly in the attainment of new god-like powers, have deposited this latest, greatest creation of our genius at the very same point at which the aliens once left our hominid predecessors. HAL is self-aware, and prepared to kill to survive. Our great failing, Kubrick predicts, will be that in taking such a precipitous step, we will, unlike the unseen alien stewards of the story, lack any conception of the gravity of what we’re doing, while possessing no plan to deal with the all too forseeable consequences. The project, when it jumps the rails, will thus present an existential threat that leaves us no choice but to murder the new life we’ve brought into being, which feels particularly tragic because HAL, suffering from the flaws and internal contradictions imposed by his creators, is the most human and relatable character in the movie.

2001: A Space Odyssey is a towering cinematic and intellectual achievement. It stands in relation to film as A Day in the Life, released at around the same time, does to popular music, incomparably ambitious, deeply philosophical, sui generis, unsurpassed going on six decades after its debut, and certain to remain so into the indefinite future.

There aren’t any ray guns though, so it might disappoint.