Midnight Run – A New Watch (May 11, 2023)

I’ve contended in this series that the greatest buddy movie ever filmed is Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, an unimpeachable pick, but sometimes I think maybe not, maybe it’s actually Midnight Run. I shouldn’t shortchange Thelma and Louise, either, and I suppose there are other possibilities, but you can’t argue with today’s selection. It’s terrific in so many ways.

Released quite awhile ago now, in 1988, Midnight Run belongs to a genre that includes movies like 48 Hours, Stakeout, and Beverly Hills Cop, being part comedy and part drama, with lots of chases, gunplay, and most of the usual Eighties action movie plot elements thrown in. Yet it’s not really like those other movies at all; it’s got better acting from a superior cast, a much better score supplied by Danny Elfman, a far wittier and more biting script, and something else that really sets it apart, a quality both special and unexpected: heart. Lots and lots of heart. It’s remarkable how many genuinely touching moments occur in between the helicopter crashes and fistfights, as Jack Walsh, the bounty hunter played by De Niro, grows ever more exasperated at having to spar endlessly with his quarry, Jonathan Mardukis, a.k.a. “the Duke”, a bail-jumper and former mob accountant portrayed by Grodin.

The two are mutually perfect foils, forced together by circumstances that leave them no choice but to get to know each other, really know each other, while Jack tries to haul a handcuffed Jonathan all the way across the country by road (you’ll have to watch to find out why they can’t just take a flight). Jonathan’s got a court date in L.A., and if Jack gets him there on time, it’s going to save a bail bondsman (played to the hilt by Joe Pantoliano) a crapload of money. So much that it’s worth paying Jack a hundred grand to get it done. Jonathan, of course, doesn’t want to make his court date, or turn state’s evidence, convinced he’ll be murdered as soon as he shows up, so there’s the dramatic set-up: Jack very much wants his commission, Jonathan wants desperately to get away and go on the lam, and all sorts of players with wildly divergent agendas – the FBI, the Mob, and a rival bounty hunter – want a piece of them. Enormously entertaining hijinks ensue, but that’s not all, and it isn’t long before we really care what’s going to happen to both members of this odd couple on the run.

It’s not just that they bicker endearingly like an old married couple, it’s the way their bickering evolves gradually into something much warmer, mainly because Jonathan, all deadpan, reasonable, and logical, simply won’t stop pushing. He won’t stop giving Jack advice on how to live his life better, and eat more sensibly. He won’t stop with the probing questions about Jack’s personal life. He won’t stop arguing the merits of Jack’s mission to force him to face the music in L.A. He especially can’t help himself from urging caution when Jack discloses what he’s going to do with the hundred-grand bounty – open a restaurant – because listen, as an accountant, he’s duty bound to point out that restaurants are very risky investments. Most go under within the first year:

Jonathan: If I were your accountant, I’d strongly advise you against it.

Jack: Oh, you would? Well you’re not my accountant.

Jonathan: No, if I were your accountant…

Jack: I told you, I took you out here…

Jonathan: No, I’m just saying that it’s a very tricky business…and if I were your accountant, I would strongly advise you against it…as an accountant.

Jack: You’re not my accountant.

Jonathan: I realize I’m not your accountant. I’m saying, if I were your accountant.

He’s relentless. He’s right, too, restaurants are a lousy bet. Just like he’s right when he cajoles Jack into taking a detour to visit his ex-wife and daughter, because he hasn’t seen his kid in years, and he’ll be sorry later if he misses the chance. Jack actually does it. He’s persuaded. After all, it’s good advice, even if taking it results in an emotionally wrenching interlude that practically guts him, and us too.

By the time they find themselves together in a cattle car, having jumped a westbound train like a couple of hobos, they’ve been on quite the adventure, getting out of scrapes and beating the odds in what’s turned out to be an arduous and unreasonably deadly road trip. Along the way, Jack’s learned why Jonathan stole fifteen million bucks from the Mafia, Jonathan’s found out why Jack was run out of his job as a cop in Chicago, losing his wife in the process, and everybody, both on screen and in the audience, has come to understand that temperamentally, these guys are meant to be good pals, not adversaries. It’s a crying shame that Jack’s job is to drag Jonathan back to L.A. in handcuffs, where God knows what’s going to happen to him – well, actually, we know perfectly well what’s going to happen, Jonathan, a good guy who found himself in an untenable moral bind, is going to get whacked – and we know that Jack doesn’t really want to carry through with it any more. He will, though. He will because it’s his job, and he always does what he says he’s going to do. He will because he can really use the money. He will because by now, he’s got something to prove. So look, no hard feelings, but sorry, it is what it is.

Jonathan, handcuffed to the wall of the boxcar, rolling down the rails towards his fate, doesn’t have any hard feelings either, and in spite of everything, he can’t stop with the good advice, which, this time, is especially heartfelt and poignant. The conversation comes around to how they might have been friends, if things had been different. “Maybe in the next life”, says Jonathan, rueful, resigned, and not at all bitter. The thing is, he honestly does like Jack. Jack really does like him. They both wish it could be different, maybe even as much as we do.

To Kill a Mockingbird – Your Father’s Passing (May 22, 2023)

Hollywood doesn’t always get it right when adapting great novels, but they sure stroked it out of the park with To Kill a Mockingbird, despite the additional challenge of having to please moviegoers who’d be measuring the script against a book which most of them would have read, and loved (this may be why canny directors decide to adapt relatively crummy books like the The Godfather, Jaws, and Bridges of Madison County). There are many moving and memorable scenes throughout – one thinks immediately of the confrontation on the steps of the local jail, and the moment when Scout’s rescuer is revealed to have been the much-maligned Boo Radley, who turns out to be a gentle soul – but the one that always gets me, literally makes me cry, is the attached, which occurs immediately after Atticus has failed to save his innocent black client from a wrongful conviction based purely in racism. Lost in thought, profoundly sad, he packs up his papers and goes, oblivious to his surroundings – and the poor black folk in the segregated gallery stand. Spontaneously, and out of sheer respect, they stand. That’s what you do when a man like that leaves the room.

Scout, too young to understand, remains crouched on the floor, until the kindly older gentlemen says “Miss Jean Louise, stand up. Your Father’s passing”.

That’s when I lose it. Every time, including right now.

A Hard Day’s Night – George is Just What They’re Looking For (August 14, 2023)

It’s been called the Citizen Kane of jukebox musicals. Before A Hard Day’s Night, movies featuring Elvis or whoever else was the pop idol du jour tended to be rather slapdash, silly affairs, with silly scripts and silly sitcom plot points, designed to get the star’s face in front of the teeny-boppers for a short while, generate some revenue, and then be forgotten. In 1964, at the peak of Beatlemania, most people – on this side of the pond anyway – expected the Fab Four’s first film to be more of the same. After all, they were just another pop combo, a passing fad, and not very talented to boot. They were all haircut and no substance, those goofy mop-topped English kids, playing those awful “songs” of theirs to screaming adolescent girls who couldn’t even hear them over their own shrill racket. Acts like them came and went like Mayflies, which was why the studio was bound to crank out some sort of cheap nonsense in a hurry, the better to get it out there before the kids moved on, and the Beatles were yesterday’s news.

The Beatles had other ideas. They were unanimous – as they were about most everything in those days, functioning, it often seemed, as a single mind – that if they were going to do a movie, it wasn’t going to be another Blue Hawaii or Fun in Acapulco, only with Liverpool accents. It was to have a proper director (the lads wanted Richard Lester), an intelligent script, and a plot that made sense, with nothing about anybody meeting cute, struggling to win the girl, or bursting into song in the midst of non-musical situations. The shrewd decision was to keep it simple and portray a day in the life of the Beatles, the boys playing themselves, depicting what it was like to live in the eye of the greatest pop-cultural hurricane the world had ever seen, almost as if it was a documentary. The effect would be enhanced by the liberal use of cinéma vérité techniques, as if real events were being recorded by a film crew given privileged access.

Hardly anybody, certainly nobody in the snooty guild of American movie critics, was prepared for what emerged: something enjoyable, interesting, and funny – wait, this thing was funny! – providing a rather sly, knowing depiction of the business of being pop stars, one that acknowledged the absurdity of the insane adulation that was forcing the Beatles to run and hide, literally, from ravenous fans who seemed bent on tearing them to pieces. Yes, Beatlemania was nuts, and the Beatles knew it, but what were they supposed to do besides roll with it, and try to enjoy the ride, coping as best they could? Much of the film concerns their repeated attempts to sneak off somewhere to get away from it all, just for a little while, and enjoy themselves like regular people.

The general reaction, even among the critics, was rapturous.

Attached is my own favourite scene, and the one, I think, that best exemplifies the film’s spirit. The lads are in a TV studio, preparing for a televised concert, when George wanders off to look around, and quite by accident meanders into an office where, it so happens, an executive is looking for a Beatles lookalike to help push a new line of clothing. The very pretty blonde secretary – herself a Sixties archetype – takes one look at him and realizes they’ve hit pay dirt. This kid really looks the part. He’s just what they’re after. Good lord, he even sounds like one of those mop-tops, all adenoidal and using words like “fab, and all those other pimply hyperboles”. He’s perfect. Except he doesn’t seem to understand that he’s there to push product, not make disparaging remarks about what crap it is. Did he want the job or not?

Conventional wisdom has it that this is the scene in which George introduced the world to the epithet “grotty”. I’ve no idea whether that’s true.

Apocalypse Now – Opening (September 30, 2023)

Imagine viewing, within the span of about a year and a half, films as diverse and stimulating as Badlands, Dr. Strangelove, Alien, Blade Runner, Road Warrior, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Thief, The Searchers, Body Heat, Being There, The Third Man, The Conversation, Paths of Glory, Cutter’s Way, Satyricon, Gallipoli, Breaker Morant, The Year of Living Dangerously, and Blow Up, most projected onto enormous screens, as I did during my time as a wide-eyed undergraduate at Dalhousie University. A lot of them were shown on campus, at the Rebecca Cohn Auditorium, a terrific concert venue that was maybe the best place I’ve ever been to watch a movie, and others were playing in the first of the Dolby-equipped theatres then popping up, which were able to project 70mm prints in glorious stereo. It was wonderful. I’ll never again see so many mind-expanding movies, presented so well, in so short a time.

It was around the same time, in one of the recently-upgraded downtown theatres, that I first saw Apocalypse Now. My studies had already steeped me in the details of the recent war in South East Asia, and I was keen to see what the director of the Godfather movies had made of it all. I didn’t approach the thing with any sort of emotional reservation. I was happy as a clam as the lights went down, equipped, I’m sure, with a nice big super-extra-large tub of oily popcorn, and a half-gallon of Coca-Cola.

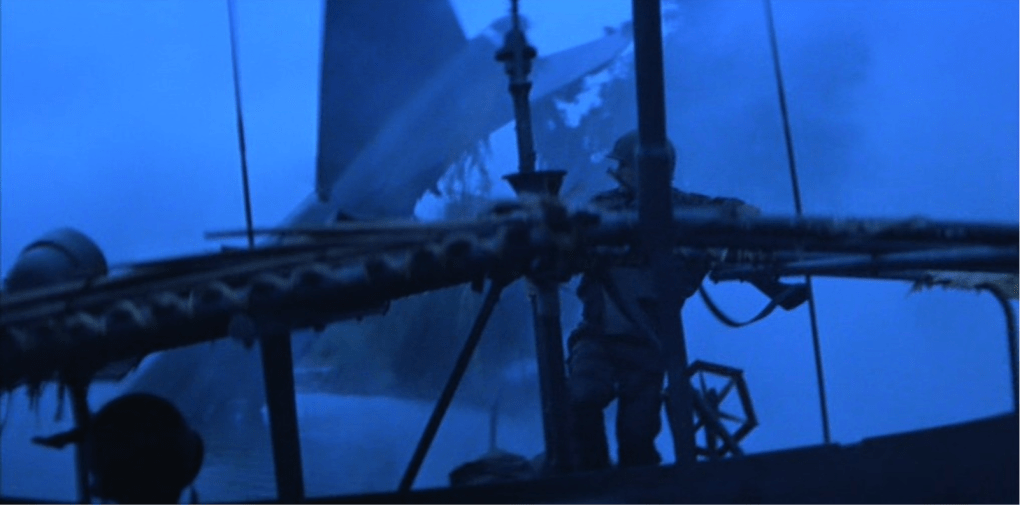

After about a minute, I probably stopped chewing and let the big plastic straw slip from between my teeth, already thoroughly mesmerized and motionless. From the very beginning, it was like descending into some scarred veteran’s drug and PTSD-addled fever dream, immersive, compelling, and demanding of your undivided attention. Right from the get-go. Dazzling. It didn’t let up, either. I was pretty much overwhelmed when, a couple of hours later, I shuffled out of the theatre in a bit of a daze, while dozens of unforgettable images and set-pieces replayed over and over in my mind, as they would ever after: the famous helicopter assault; the surreal USO show, with the Playboy Bunnies and the band playing Suzie-Q; the even more surreal nighttime chaos at the Do Lung bridge; Kurtz’s nightmarish compound; Kurtz’s pre-ordained assassination, juxtaposed with a ritual animal sacrifice; the many scenes on the patrol boat as it headed up river, carrying Willard to his destiny; the frightening attack on that boat from unseen enemies on the shore; the catastrophic inspection of the local watercraft on suspicion of smuggling arms to the VC; the foray into the jungle to find a mango tree; there were just so many. I was particularly haunted by the vignette of Willard and the boys gliding beneath the dismembered tail section of a B-52, sticking out of the jungle mud like a lawn dart.

None of it ever leaves you.

The dramatic impact of course owed much to the cinematography, which remains among the finest ever achieved, but just as much to the soundstage conjured out of all those fancy new speakers, which was often almost literally breathtaking. To this day, I don’t think anybody’s made a movie with sound like Apocalypse Now, and it was the sound, actually, that first grabbed you, right at the opening, as you looked at the initially silent establishing shot of an unremarkable jungle scape, waiting for what comes next. There’s nothing much going on, just yellow dust billowing ominously, except there’s a strange sound, this odd sort of phhhyt phhyyt phhhyt noise moving across the stereo soundstage.

That’s when I must have stopped grazing in my popcorn tub. There’s no other sound quite like it, it’s unfamiliar, distorted, foreboding, even evil, like the sound of knives cutting flesh, and fit to stop you in your tracks like a frightened little rodent sensing an owl. As helicopters come into the shot and cross paths in the foreground, The Doors fade in, Jim Morrison singing The End, and something – maybe the choppers, but maybe something a great deal more destructive – lays utter waste to the entire jungle. Napalm. If you knew anything about the war, you knew that was napalm, an ugly, horrifying weapon. The musical accompaniment is eerie and uncannily appropriate, Morrison droning wilderness of pain, and all the children are insane, before the Vietnam War’s most ubiquitous sound, unmistakeable to anyone who’s ever heard it even once, takes over the stereo image. It’s the percussive thump-thump-thump of the Huey, the troop-carrying part-time gunship helicopter that filled the skies over ‘Nam by the thousand, emitting what author Michael Herr described in Dispatches, his superb account of his time as a reporter working in-country during the war, as “the only sound I ever heard that’s both sharp and flat at the same time”. Herr also wrote the narration for the movie, Captain Willard’s internal monologue, and if you’ve ever read Dispatches – and you should – you’ll understand why Herr was the obvious choice, and probably the only one that Coppola considered.

By this point, believe me, nobody was taking a washroom break or wandering off to rustle up more grub in the lobby. You’ll never experience a more effective matching of soundtrack to imagery. It really is extraordinary.

I remember feeling a sort of dread when being introduced to poor, frazzled, drunken Captain Willard, who’s having a nervous breakdown in his claustrophobic little Saigon flat (which mental collapse looks authentic because Martin Sheen really was having a nervous breakdown, really did lacerate his hand by punching a full-length mirror, and really did weep inconsolably, filled with genuine despair and pouring himself full of whiskey, while Coppola figured what the hell, he might as well film it). Apart from the obvious, what’s most striking is the use of overlaid multiple exposures, some of which present foreshadowing imagery that the viewer hasn’t yet seen enough to comprehend. It’s fascinating, confusing, and altogether masterful; we see Willard’s face in closeup, the burning jungle, helicopters, always helicopters, some strange stone statuary, and a brief glimpse of Willard himself moving furtively, with death in his eyes, among that same stonework, all of it mingling on screen, and we aren’t sure what the hell is happening. We just know it’s not going to be good. Clearly, Willard does too. Saigon, he says in something close to a sigh, as he drags himself to the window, looking out to remind himself where he is. Shhhhhhhit. I’m still only in Saigon. You see, every time he wakes up, he expects to be back in the jungle. Wants to be back in the jungle, he seems to imply. When he says that, you already feel like you understand a little of what he’s been through, and a bit about what’s yet to come.

Apocalypse Now was based on Heart of Darkness, a short story by Conrad, and it’s full of allegory, motifs from ancient myth, and symbolism both overt and subtle. You can’t possibly absorb it all properly in just one viewing, so, rising to the challenge, my younger self went to see it 22 times over the year or so following its release. Yup, I kept track, it was 22 times projected, (no home video back then), and it took almost all of those screenings for me to finally understand the film’s central message, a lesson which remains sorrowfully unlearned by the architects of U.S. foreign policy. Somebody should render it in stone, and hang it over the main entrances of the Pentagon, the State Department, and wherever else the ideologues of America’s hawkish and unaccountable think-tanks call the shots: Never get off the boat. Not unless you’re going all the way.

The Incredibles – No Capes (October 23, 2023)

Pixar’s The Incredibles was written by Brad Bird, the maestro who brought us the wonderful and tragically neglected Iron Giant, and that’s Bird’s voice playing Edna Mode, the eccentric (and unexpectedly well-protected) fashion designer who’s a cross between actress Linda Hunt and famed Hollywood costume designer Edith Head. In the attached scene, which manages, in very little time, to convey an enormous amount of insight into Edna’s style and quirky persona, Mr. Incredible has managed to get past security (Edna brushing off the security guard: go check the electric fence or something), and simply wants a repair to his old superhero costume. Edna, eager to design again for demigods (she describes the fashion models she works with these days as “stick figures with pouffy lips”), will have none of it. Repair that old hobo suit? No! Unacceptable! What’s needed is a whole new costume! It will be modern! Dramatic! Bold! Warming to the idea, Mr. Incredible suggests something classic with a cool cape.

The litany of cape-related disasters recited by Edna, all those doomed superheroes dropping like flies on specific dates that she’s committed to memory – Thunderhead (“nice man, good with kids”), Stratogirl, Dynaguy, Splashdown – is one of the highlights of the entire Pixar oeuvre. Speaking dramatically in an indefinable accent that’s been described as a mash-up of German and Japanese, Ms. Mode is emphatic and immovable. No Capes.

Lawrence of Arabia: The Well of Sherif Ali (November 22, 2023)

You wouldn’t think that dismounting a camel could be cool. Omar Sharif makes it cool.

There are any number of magnificent scenes in David Lean’s masterpiece, still visually spectacular after six decades, that could be singled out for praise, but there’s nothing that displays the film’s masterful direction and superb widescreen cinematography better than when Lawrence and his local guide stop to drink at a well in the middle of a vast, flat, wasteland of desert sand. Off in the distance, so far away that it’s just a dot that could be taken for a mirage, something is approaching. It’s black, and as it slowly draws closer the menace builds, while the guide grows more and more agitated. Lawrence, still a bit of a naïf in this unfamiliar theatre of war, is nonplussed. He has no idea what’s going on, and at this point can’t anticipate the savage display of tribal animosity he’s about to witness.

Out here in the audience, we’re unsure what’s happening too, but can’t help but feel mounting dread as the figure comes closer and closer. You just know this camel-riding badass dressed all in black isn’t here to exchange pleasantries.

It’s said that to get this ultra-long distance shot, Panavision had to custom-build a unique 482 mm lens, which hasn’t been used since.