Almost Famous – Lester Bangs (January 10, 2024)

This is Ben Fong Torres, right? O.K. Tell him it’s “a think piece about a mid-level band struggling with its own limitations in the harsh face of stardom”. He’ll wet himself.

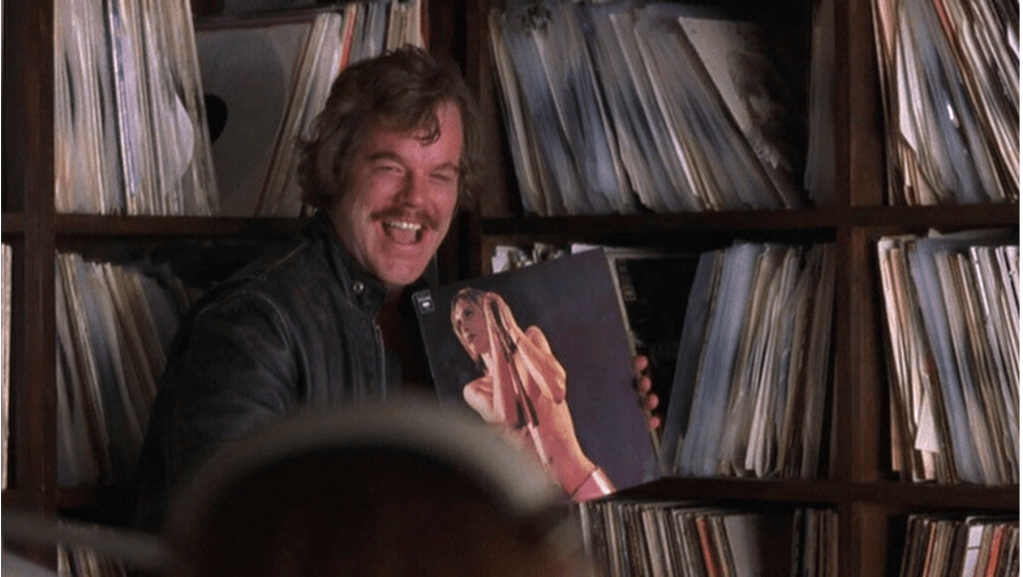

If there’s a movie in which Philip Seymour Hoffman isn’t pitch-perfect and brilliant, Cameron Crowe’s wonderful Almost Famous certainly isn’t it. His is one of the key performances in a film that manages to capture the true essence of that strange moment of cultural transition in the early 1970s, when the Sixties were over, but not quite, and certainly not musically. Disco, Punk, and the full-scale Invasion of the Singer-Songwriters were still in the future, the whole West Coast Eagles/Fleetwood Mac thing hadn’t yet kicked into high gear, nobody had yet heard of the Captain and Tennille or the Starland Vocal Band, and established acts like the Who, the Stones, and Rod Stewart were putting out albums that stood with, and in a way were still among, the best of the Sixties – check out, for example, Who’s Next, Exile on Main Street, and Every Picture Tells a Story, enduring classics released during 1971-72. Badfinger was out there picking up where the Beatles left off, Bridge Over Troubled Water and Tapestry were huge sellers, and it might have seemed that everything was rolling along just as it should. But there were those, like the legendary music critic Lester Bangs of Creem Magazine, who could feel the rot setting in, and smell the creeping corporatization of Rock as it became a big business.

It may seem that Hoffman’s portrayal of Bangs is a little kind, given the way dispassionate observers usually portrayed him. An article in the New Yorker put it this way:

Lester Bangs was a wreck of a man, right up until his death in April of 1982, at the age of thirty-three. He was fat, sweaty, unkempt—an out-of-control alcoholic in torn jeans and a too-small black leather jacket; crocked to the gills on the Romilar cough syrup he swigged down by the bottle. He also had the most advanced and exquisite taste of any American writer of his generation, uneven and erratic as it was.

https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/lester-bangs-truth-teller

A brilliant but erratic and off-putting kook, then. Maybe, to most. But he was also a fabulous writer, keenly perceptive, smart as a whip, and funny as hell, and remember, Cameron Crowe knew Bangs, up close and personal. Almost Famous is semi-autobiographical, with young William Miller standing in for the director, and it’s a safe bet that the on-screen conversations between Bangs and his teenaged protéger echo those that actually occurred all those years ago, as do many of the weird and wonderful episodes depicted during Miller’s cross-country rollercoaster ride with emerging band Stillwater, a fictional outfit merging the personal traits and foibles of the members of the Eagles, Led Zeppelin, and a few other up-and-coming bands that Crowe toured with as a budding writer for Rolling Stone.

What a way to grow up, eh?

Those who really knew him invariably describe Bangs just as Hoffman plays him, sympathetic, helpful, full of really sage advice, and profoundly influential in their own lives and career choices. Crowe, obviously, loved the guy, and it was a tribute to Hoffman that nobody else was even considered for the role, plain as it was to the writer/director that nobody else had the range and emotional depth to do right by his screenplay. Even at that, Hoffman exceeded all expectations, particularly in the pivotal scene in which William reaches Lester late at night, all in a panic, and Lester talks him out of his tree, reminding the kid that he’s just not cool like the people he writes about, and shouldn’t want to be. Cool people are boring. Their art never lasts. It’s the nerds like us, insists Lester, the guys home alone on Friday nights, the guys who never get the pretty girls, who turn angst into real art that stands the test of time, impliedly and generously accepting William into a select group of fellow writers. This is what Cameron Crowe wrote about Hoffman’s performance in 2014, upon learning of the actor’s untimely death:

My original take on this scene was a loud, late night pronouncement from Lester Bangs. A call to arms. In Phil’s hands it became something different. A scene about quiet truths shared between two guys, both at the crossroads, both hurting, and both up too late. It became the soul of the movie. In between takes, Hoffman spoke to no one. He listened only to his headset, only to the words of Lester himself. (His Walkman was filled with rare Lester interviews.) When the scene was over, I realized that Hoffman had pulled off a magic trick. He’d leapt over the words and the script, and gone hunting for the soul and compassion of the private Lester, the one only a few of us had ever met. Suddenly the portrait was complete. The crew and I will always be grateful for that front row seat to his genius.

Hoffman, like Bangs before him, was killed by drug addiction. In his obituary, the NY Times described him as “perhaps the most ambitious and widely admired American actor of his generation”, and I’ve never encountered criticism or commentary that said any different. The man had a gift.

I’ve found it’s best not to contemplate the monstrous cumulative loss of talent and human potential inflicted upon our culture by drugs. I don’t follow that advice myself, of course, but you should try.

There are lots of other reasons, besides Hoffman’s portrayal of Bangs, to watch Almost Famous. Everyone is terrific, and the film is by turns hilarious, nostalgic, wryly observant, and almost unbearably poignant, with a core of pure human decency. If you’ve never seen it, do yourself a favour, maybe the next time you’re feeling grumpy or depressed. There are scenes that will stick with you for the rest of your life.

Nobody – Brawl on the Bus (January 15, 2024)

Nobody starts out by introducing us to the hum-drum, excruciatingly ordinary life of, yes, an apparent nobody named Hutch Mansell, played wonderfully by Bob Odinkirk. Nothing much happens in this guy’s life. He’s got an unfulfilling job, a wife and kids who don’t seem to like him all that much, and a nice but modest sort of middle class suburban home. The central drama of his life involves domestic waste disposal. He keeps failing to roll out the trash bins in time, routinely getting the unwieldy things to the curb just a few seconds after the garbage truck has pulled away. Happens every damned time. And that’s about it for Hutch in the excitement department. We’re left to wonder how such a monochromatic drudge ever managed to snag himself such a gorgeous wife (portrayed by Connie Nielsen, who’s out of all of our leagues, we’re being honest).

Then a couple of punks break into his house in the middle of the night, and, well, things start happening, there’s a sort of chain reaction, while we in the audience follow the bouncing ball and begin to gather that Hutch here isn’t at all what he seems. Clearly, he’s got a back story that involves something a little more, ummm, intense than sitting behind a desk shuffling paper. But what? In one scene, a guy notices one of Hutch’s tattoos, blanches, and quietly exits the room through a steel-reinforced door, locking it behind him. Hunh. That’s gotta mean something, right? We’re still playing catch-up when Hutch has an entirely random but fateful encounter with a gang of sneering, despicable expat Russian thugs on public transit. These bastards think it’s great fun to harass a vulnerable and terrified young woman who’s sitting there all by herself. They obviously think she might be just the prey item to round out another carefree night of violent, soulless debauchery.

Hutch has other ideas.

One of the crappiest aspects of the generally crappy latter-day action movie genre is the complete absence of real-world physical consequences arising from even the most outlandishly violent actions. This tends to dumb down the narrative even when the protagonists aren’t stupid-looking super-heroes who couldn’t get hurt if you ran them through a combine harvester. In the movies, it’s also purportedly regular people, guys who might be tough but aren’t named Thor or have skeletons forged out of adamantium or any such shit, who don’t get all that bent out of shape when they’re assaulted with things that would immediately put an end to thee and me. They take bullets right through the sternum, yet never wind up with the logically inevitable sucking chest wounds. They get smacked upside the head with baseball bats, and instead of dropping like sacks of wet cement, they shake it off and come back for more. Nobody gets his teeth knocked out. Noses don’t break and bleed profusely. Eyes aren’t swollen shut. Nobody goes cross-eyed from a left hook that would have knocked a young George Foreman right into the middle of next week. They go at each other hammer and tongs in protracted bare-knuckle slugfests, and nobody so much as breaks a finger. Next scene, the guy who just got hit in the face with a dining room chair doesn’t have so much as a black eye.

Yeah. Nobody isn’t like that. In this movie, when you beat the living shit out of somebody, he subsequently looks and behaves as if somebody just beat him literally shitless. Nobody on that bus, save the woman whose peril serves as the catalyst for the entire bloody, bone-crunching, atavistic melee, gets out of the fight in one piece, not the scumbags, and not the hero either. It’s the ugliest, and God help me the most exhilarating, caveman fight I’ve ever seen on screen, and when it’s finally over, we know that somehow, prior to becoming a suburban drone, Hutch used to work for folks who sometimes found it convenient if certain vexatious people didn’t, you know, make it through to the next morning. Like Liam Neeson in the greatly inferior Taken franchise, Hutch is in possession of a particular set of skills.

At this point in the film, the bad guys don’t know what they’re up against. There aren’t a lot of movies that offer anything near so satisfying as watching the whole stupid lot of them fuck around and find out.

Terminator 2 – Chase in the L.A. River (February 8, 2024)

Wowsa. I remember sitting in the theatre waiting for T2 to begin, and as the lights began to dim I had my doubts that James Cameron would pull it off. He had a tough act to follow, even if it was his own. I was a huge fan of the original film, especially Michael Biehn’s portrayal of Kyle Reese, a soldier on a mission he probably doesn’t have the means to accomplish, but has to attempt anyway, even if, as seems inevitable, it costs him his life. I was utterly won over by the scene in the fleeing car following the melee in Tech Noir, when young Sarah Connor, a thoroughly unimposing waitress at a fast food joint, begins to believe Kyle is who he says he is, and that she really is on the hit list of an invincible cyborg assassin from the future (underneath it’s a hyper-alloy combat chassis. Micro-processor controlled. Fully armoured. Very tough). “Can you stop it?”, she asks, fearing the answer, and Reese tells her no lies. You can sense both determination and something close to resignation in his pained, matter-of-fact reply: “I don’t know…with these weapons? I don’t know”. Maybe he can’t. But he sure as Hell means to try.

Biehn really sold it. You believed Reese, just like Sarah did. From there it all just hung together in a way that sci-fy/action movies, particularly those involving time travel, rarely do, while seducing the audience into making a huge emotional investment in the outcome; for behind all the science fiction razzle-dazzle, Terminator 1 was, believe it or not, a character-driven love story. It relied upon the same thing that elevated Jaws above others of its genre: you really cared about these people. But Reese dies at the end, and Biehn wouldn’t be back. All that chemistry between Kyle and Sarah was lost. Anyway, what was there left to do? The ending of the first movie didn’t seem to leave any logical room for a sequel.

It didn’t take long for all such doubts to evaporate under the hot light of what remains, over 30 years on (!), one of the greatest action movies ever filmed. The attached scene is the first big set-piece, occurring at an early stage of the story when the viewer isn’t really sure what’s going on. There seem to be two Terminators stalking this kid, one identical to the unit in the first film, the other much different, though we don’t yet understand the horrifying extent of this new model’s capabilities. When the two Terminators lock horns in the maintenance corridor behind the galleria, and you realize that Arnold is the new Kyle, and has just about as much hope of besting his foe as Kyle did, you just knew, boy, was this going to be good. The subsequent chase through the concrete bed of the L.A. River, with Arnie on his big bad Harley tearing after an enormous tow-truck about the size of an 18-wheeler, while firing and spin-cocking his Winchester in the same way that John Wayne used to do it, is one for the ages, creating expectations that are fully borne out by the rest of the film. We’re made to understand that Arnold’s Terminator, just like his predecessor, absolutely will not stop trying to fulfill its mission, not ever, no matter what. We also know, having experienced just a little of the power of his terrifying liquid metal antagonist, that the unflinching resolve of an old T-800 unit might not make any difference.

Singin’ In the Rain – Title Song (February 15, 2024)

In the midst of a gloomy and darkening year, it seemed like a good time to revel in an old-fashioned song from a bygone era, back when there was seemingly insatiable public demand for the sort of gentle, escapist fun to be had from the great MGM musicals. Singin’ in the Rain isn’t about anything more weighty or thought-provoking than boy-meets-girl, and sometimes the stitching of the big musical numbers into the narrative is a little forced (the idea is that they’re all part of the movie biz, so anything could be going on as they observe other films in production), besides which it’s often a little silly, but nothing can dim the brilliance of the big set-piece in which Gene Kelly sings and dances his way through the title song. Kelly’s balletic grace was rivalled only by the likes of Nureyev and Baryshnikov, and just like the great male ballet stars he oozed physical prowess and masculinity (to a much greater extent than his only possible peer in the business, Fred Astaire). Nobody could look at this performance and think that dancing is no sort of career for a man’s man.

It’s incredible that this whole scene was filmed indoors, on a sound stage, with sprinklers above supplying the rain (I’ve always wondered, what sort of drainage did they have to cooper together to deal with all that water?). It looks like one long continuous shot, but actually took three days to film, during which Kelly developed a fever that reached a very dangerous 103 degrees F. This didn’t do any more to slow him down than the progressive constriction of the wool suits the costume department kept giving him to wear, even though they shrank when they got soaked. Look, anybody can do a big, choreographed song and dance routine for the cameras when they’re perfectly dry and healthy; Gene Kelly came to play.

Look at him. When he’s not stomping his exuberant way through puddles, he just floats.

My favourite part comes at the very end, when Kelly is confronted by a beat cop who’s obviously wondering whether he’s got a loon fit for the straitjacket on his hands. The sheepish, yet good-humoured manner in which Gene explains in song that he’s just dancing and singing in the rain is utterly, disarmingly endearing. No problem here, officer. He smiles and walks away, handing his umbrella to a passer-by. What’s he need it for? Nothing can dampen this guy’s spirits. He just found out that the girl he loves might love him back.

This Is Spinal Tap – Stonehenge (March 21, 2024)

It’s one hilarious scene after another in This is Spinal Tap, Rob Reiner’s hilarious (and ground-breaking) “mockumentory” about the witless mediocrities of an aging prog-rock/hair metal band struggling to remain relevant and keep their day jobs whilst fumbling from one humiliating fiasco to the next. The Stonehenge bit is the part that people seem most apt to remember, so here it is, from Nigel’s back-of-the-napkin concept drawing, to the fabricator’s presentation of the finished product (that’s a young Angelica Huston), through the debacle on stage, and the bitter backstage aftermath. Unfortunately, the clip omits what I always thought was the best line, delivered by David St. Hubbins to their manager when the latter points out that the diminutive trilithon replica was actually assembled precisely to match Nigel’s rough blueprint, which mixed up the symbol for “feet” with the one for “inches”: “But you’re not as confused as him, are you? It’s not your job to be as confused as Nigel”.

Here:

The most surprising aspect of the film was the band’s delightfully godawful music, which was actually almost exactly like the shite then being pumped out by the bands of the era, only a little more listenable, all of it written, believe it or not, by Reiner and the actors playing the band, Christopher Guest, David McKean, and Harry Shearer. For me, the most deliciously satirical number was Big Bottom, the lyrics of which were wittier than anything from the supposed “hard rock” of the era:

The bigger the cushion, the sweeter the pushin’

That’s what I said

The looser the waistband, the deeper the quicksand

Or so I have read

My baby fits me like a flesh tuxedo

I’d like to sink her with my pink torpedo

Big bottom, big bottom

Talk about bum cakes, my girl’s got ’em

Big bottom drive me out of my mind

How could I leave this behind?

Genius! Then there’s this little musical interlude, with Nigel coming off like a student of music theory before dropping the hammer:

The hell of it is, Lick My Love Pump actually does sound kind of pretty, doesn’t it?

Throughout, they’re all just so endearingly, obliviously befuddled, their morale declining as cock-up upon cock-up combines with the usual toxic group dynamics (there’s even a Yoko Ono/Linda McCartney stand-in), while the disapproving oversight of their corporate record company overlords threatens to derail what’s left of their career (“listen”, pleads the manager, dealing with the wrath of one executive, “you should have seen what they wanted to put on the cover”). In one scene they literally get lost in the labyrinth of hallways beneath the stadium, and can’t find the stage; in another they find themselves booked into some sort of dance party on a frigging air force base; finally, as the group disintegrates, and Nigel marches out in a huff, taking his songs with him, the rump is left to play to half empty amphitheatres in amusement parks, where they try something new by performing bassist Derek’s Jazz Odyssey (a “free form jazz exploration”). Much of their charmingly dim-witted banter was improvised, and I’ve always wondered how much of the “this goes to eleven” scene was just Christopher Guest making stuff up off the top of his head (Nigel, describing a favourite guitar: “It’s famous for its sustain, I mean you can just hold it, aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa – you could go have a bite, and aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa.”)

You cant help but love the adorable dum-dums, and their terrible songs too. Listen, I’d take these guys over Twisted Sister or Quiet Riot every day of the week.

Watch this, on the creation of Nigel:

The Conversation – Harry Merges the Tapes (April 23, 2024)

Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation, an overlooked masterpiece of bleak mid-1970s film-making, is one of those quiet, contemplative little movies, almost an art house production, that the big studios used to bankroll back in the old days, before everything became about spaceships and superheroes in skin-tight outfits battling with CGI aliens and monsters (though upon its release, the first Superman movie was just four years over the horizon, and Star Wars would be along in only three to usher in the era of special effects comic book movies designed as much to sell toys as tell a compelling story). A pure product of its paranoid, depressive, post-Watergate era, it’s of a piece with films like The Parallax View, Chinatown, Three Days of the Condor, Network, and Klute, movies about ambiguity, amorality, corruption, dark forces pulling the strings from behind the scenes, and not-so-happy endings; it’s also a lot like Antonioni’s head-twisting Sixties tour de force Blow-Up, which likewise examined the sometimes misleading subjectivity of perception, and the elusiveness of truth.

The great Gene Hackman plays Harry Caul, a sound surveillance expert famous in the community for being able to bug anybody, anywhere, no matter how difficult the conditions. He’s been tasked with recording a conversation between a pair of lovers as they walk in circles around a noisy public plaza, an almost impossible assignment that he pulls off with the use of multiple microphones deployed by a number of operatives stationed in and around the area, one pointed from atop a billboard, another out of a high window, another being carried in a shopping bag, and so on, each capturing a piece of the dialog, as depicted in the first attachment. It’s one of the most immediately gripping opening sequences ever filmed; straight away, without any sort of preliminary exposition, the viewer is placed right in the middle of the crucial moment upon which everything’s going to turn (readers of a certain age may recognize Robert Shields, of the soon-to-be-famous mime team Shields & Yarnell, performing some street theatre in the plaza before Hackman enters the picture). In the second scene, Harry puts it all together, synthesizing the tapes to form a single seamless recording in a fascinating demonstration of technical mastery, in this case with sound equipment, that’s highly reminiscent of the process by which professional photographer David Hemmings, the protagonist in Blow-Up, works with imagery as he makes successive enlargements of an enigmatic set of shots of a couple he took in a park, trying to get to the bottom of what he thinks he might have captured on film (I love how you can hear the wind blowing through the leaves as Hemmings stares intently at the increasingly indistinct imagery):

Both men reach the troubling conclusion that they’ve gathered evidence of murder plots, and in both cases that evidence is stolen, leaving them with nothing they might take to the authorities, much less any certainty about what they might have been on the cusp of proving. In Blow-Up, we’re left to wonder what really happened, finally, and even whether Hemmings really captured a murder in progress after all (he discovered a body, but it vanished too – was it all an illusion?), while The Conversation ends with the realization that somebody was murdered, all right, but not the ones Harry took to be the intended victims. He’d gotten it all wrong, all because of his mis-hearing of a haunting, unforgettable nuance of verbal emphasis that nobody who’s seen the movie can ever forget: “He’d kill us if he had the chance”.

The Wrong Trousers – Train Pursuit (June 9, 2024)

For my dough, there exists no animated feature more clever, more nuanced, more full of endearing silliness, more out-and-out hilarious than the Wallace and Gromit adventure The Wrong Trousers, produced by Nick Parks and the talented folks at Aardman studios. The action begins when Wallace, in dire financial straits, decides to let out a room and take in a lodger, who turns out, most wonderfully, to be an evil, cat-burgling penguin. An evil penguin, mind you (who turns out to be named Feathers McGraw), with beady little black eyes, who’s mute, oozing menace, and obviously up to no good, as Gromit discovers when he tails the little rotter on one of his mysterious nighttime forays. The felonious bird is casing a joint he intends to rob! OMG! Hijinks, as they say, ensue, until the movie climaxes with the attached set piece, as our heroes engage in a frenetic chase on a model train kit, trying to apprehend the scheming antarctic thief as he attempts his getaway by (HO scale) rail.

This action sequence is so creative, intricate, and full of twists and turns that it’d be impressive if it was CGI; to have filmed it using the incredibly painstaking, downright agonizing process of stop-motion “claymation” is an achievement that practically beggars belief. It almost hurts to think about how long it must have taken to manipulate those little clay figures to create the frantic pursuit in Wallace’s living room, with the animators moving a part of a clay figure a millimetre, shooting a frame, moving it another millimetre, shooting a frame, ad nauseum, adjusting several characters at once, with truly exquisite attention to all the little kinetic details of fast-moving objects and the physics they obey. Think of the bit when Gromit is desperately laying new track in front of his speeding back end of the train – for that alone, we’re probably talking hundreds, if not thousands, of person-hours. Or think about all those spinning wheels on the train. Honestly, the mind boggles. This mini-documentary shows how it’s done:

Six weeks of prep, and three weeks of stop-motion animating, to produce one minute of film. At the end of it, though, the clay figures aren’t just moving, they’re performing.

Listen, if you’re not tickled pink by Wallace and Gromit, especially by this, which I’d argue is the greatest scene from their most entertaining feature, well, I’d advise people and other living things to give you a wide berth. Best to just let you march around grinding your teeth by yourself.

Saving Private Ryan – Omaha Beach (June 23, 2024)

Having written recently about D-Day on its 80th anniversary, and the epic achievements of the Allied forces on June 6, 1944, it occurred to me that no series of postings on great movie scenes could possibly omit Saving Private Ryan‘s depiction of the storming of Omaha Beach, upon which the toughest fighting occurred.

The headline pasted in above comes from an article written by Tom Ward of Esquire in 2023, and while I’ve tried to think of another contender, I really can’t. Not even the night assault in Platoon, the helicopter attack in Apocalypse Now, or the depiction of the Viet Nam battle of Ia Drang in We Were Soldiers puts you right there amid the horror in quite the same way as Spielberg’s recreation of the assault on Omaha, one of the five code-named beaches upon which the D-Day landings occurred. Spielberg has said that as he consulted with various experts, historians, and witnesses in preparation for filming, the veterans who’d been there that day, to a man, urged him not to sugar coat it in any way. They wanted him to let people see what it was like, and strip them of their illusions. Maybe then they’d learn something valuable. The director did his best to honour their wishes, and set out to make his portrayal hew as closely to the brutal, gory reality as he could, knowing he didn’t have to make anything up, or exaggerate any of the details. He just had to remain true to the human experience of the kids pouring out of their landing craft, which, on Omaha, was particularly gruesome.

An impossibly huge number of things went according to plan on D-Day, making it, arguably, the greatest single feat of arms in military history, but of course there had to be some number of failures, cock-ups, and plain stupid mistakes, amplified by the bad luck that has to attend at least some portion of any endeavour as huge, with as many moving parts, as a full-scale invasion of Europe. So it was on Omaha Beach, where one thing after another went wrong. Allied heavy bombers were supposed to have blasted the defences to oblivion prior to the landing: bombing blind through thick cloud, they missed entirely, despite dropping something like 13,000 bombs. Bombardment by the enormously powerful guns of the numerous battleships on hand for the invasion should likewise have neutralized the defences, heavily fortified though they were; the shelling wasn’t accurate enough to have any significant effect. The troops were supposed to come ashore in the company of ingeniously modified Sherman tanks, which had been equipped with canvas skirts and little propellers allowing them to float, and swim ashore; they were put into the water too far out from the beach, and foundered before they could make it to dry land. Unusually strong winds and tidal currents pushed the landing craft away from their intended landing spots, leading to much confusion and a dangerous dispersion of forces. Perhaps worst of all, the Germans, though they expected the attack to come at Calais, hadn’t neglected the need to build fairly heavy defences all along the coast (an “Atlantic Wall” which, incredibly, stretched from France all the way to the northern limit of Norway), and put Erwin Rommel in charge; Rommel not only placed all manner of traps and obstacles on the beaches to thwart any movement ashore, he intuited that the one we’d code-named Omaha was a very likely landing spot, owing to its similarity to the beach at Salerno, which had been used for amphibious landings in the Italian campaign. The High Command thought Calais was where the blow would fall, but Rommel had other ideas, and the Germans were thus better prepared at Omaha than at any of the other landing sites.

The result was 2,400 casualties, many more than at any of the four other landing beaches (the forces that hit Utah beach suffered fewer than 200, and the British at Gold Beach lost 400). By the standards of warfare conducted on this scale this wasn’t anything close to an utter bloodbath, and the Americans weren’t thrown back into the sea – by nightfall they’d put over 34,000 troops ashore, despite everything the Germans could do, which under the circumstances was an outstanding achievement – but for the boys crawling up the beach amid withering artillery and machine-gun fire, it was terrifying, bloody, and, as Spielberg is at pains to depict, shockingly disorienting. Spielberg was masterful in his use of sound, camera angles, rapid cuts, and often blurry cinematography to convey the stunned, almost wholly incapacitating confusion of finding oneself in the middle of all those horrendous blasts, with fellow soldiers dropping left and right, blood and body parts flying all over the place, and the surf turning red from the hemorrhaging of all those who didn’t even make it out of the water before being cut to ribbons.

It’s one indelible image after another. The GIs being mowed down by machine guns the moment the ramp drops on their landing craft. Men, trying to avoid the incoming, jumping over the sides of their landing craft too far from the beach, drowning in deep water under the weight of their gear. A soldier with a flamethrower being hit and exploding in a blast of napalm. A wounded soldier pausing for a moment, then turning back to retrieve his severed arm, carrying it in his remaining good hand as if somebody might later reattach it for him. The frantic triaging as Army medics try to save who they can, and ease the pain of the rest. Those who’ve made it as far as the shelter of the sea wall running back on to the beach to strip ammo belts and other useful gear off of the dead and the pitifully wounded, still writhing in agony, who’ll no longer have any use for it. A grunt yelling LET ‘EM BURN, urging his comrades not to put anyone out of his misery with gunfire as the blast of a flamethrower blows burning German gunners right out of the front of their pillbox. The merciless shooting – execution, really – of Germans trying to surrender. Captain Miller, struggling to get a grip on himself and figure out what to do as he shelters amid the big metal tank traps, half-concussed and just about ready to succumb to PTSD from all the fighting he’s seen already, none of it as horrible as this. Jackson, the deadly sniper, quoting scripture as he takes aim and delivers the blow that turns the tide for Miller’s company, in a moment of calm, ruthless, surgical killing that feels like Divine deliverance.

I’ve read that even at that, you only really get a dim sense of it. The terror, the adrenaline, the deafening noise, the sudden, repeated loss of friends and comrades-in-arms, the feeling that overcomes you when you go from figuring you’re going to be O.K. to realizing you’re almost certainly going to be turned into ground chuck within the next couple of minutes, are all, finally, impossible to properly convey. But Spielberg comes as close as anyone ever will.

Saving Private Ryan was beat out for the Best Picture Oscar by Shakespeare in Love. Perhaps the truths it conveyed were too much for the Academy voters to digest straight away, in which case I guess I can understand. They were meant to be.

2001: A Space Odyssey – Lobotomizing the HAL 9000 (August 18, 2024)

A lengthier essay on one of the greatest films ever made.

I expect that opinions out there among the gen. pop., as opposed to the guild of movie critics or the community of dedicated film buffs – especially among those who weren’t even born when Star Wars was first released, and have had their expectations of science fiction shaped by movies in which vehicles travelling through the vacuum of space make whooshing sounds, have wings, and maneuver aerodynamically – are, at best, divided about Stanley Kubrick’s incomparable masterpiece. The pacing is deliberate, the evolving mystery is unusually opaque, the physics of space flight are depicted as plodding and tedious (which is to say, with scrupulous accuracy), the tone is dispassionate and cerebral, and nobody has warp drives, transporters, or even ray guns. Unless you pay close attention, you may have trouble even understanding what the film is about. Many seem never to figure it out regardless of how hard they try.

Even audiences back in the day, whose attention spans, safe to say, were a wee bit more robust than those of the generation weaned on smart phones and tablets, were often as not left utterly perplexed; contemporary commentary often boiled down to “???”. Most modern viewers, perhaps sitting there waiting for the appearance of the Klingon battle cruisers, or maybe for Darth Vader and some of those cute furry Ewoks to show up, aren’t liable to have any better understanding. I get it. Nothing is spoon-fed to the viewer. There’s little exposition and minimal dialogue. It’s therefore not immediately obvious what’s going on. What’s with all those apes at the start? What’s that strange black rectangle, how did that get there, and what for? Why do we then jump from millions of years in the past to what was then, when the movie hit theatres, several decades in the future? Why is there another rectangle buried on the moon? Why has a mission been sent to Jupiter? Where the hell is astronaut Dave Bowman going (or being taken?) at the end, why does he wind up in what looks like a replica of a bedroom at Versailles, and why is there yet another of those frigging rectangles in there with him? Then – hunh? – it all ends with a floating foetus in some sort of ghostly womb, drifting through space? WTF? No, seriously – WTF?

Based on a short story by Arthur C. Clarke titled The Sentinel, the film’s sometimes confounding plot elements, and the quite deliberate ambiguity of many of its most crucial sequences, derive from a number of premises Kubrick adopted from the great science fiction writer, with whom he worked closely throughout: that humanity’s initial forays into space were as epochal an evolutionary development as the primordial colonization of dry land by the first sea creatures to venture ashore; that any technology sufficiently advanced over your own will appear to you as magic; that intelligent alien life would almost certainly be incomprehensible to us in both form and intellect, and therefore seem god-like; and that our species was still essentially in its evolutionary infancy, yet was now in the process of creating technologies beyond our ability to control, putting us at risk of extinction. The breathtakingly ambitious intellectual challenge that Clarke and Kubrick set for themselves was to wrap all these themes together into a movie that depicted the near future of manned space flight with unprecedented accuracy, exquisitely detailed authenticity, and, to the fullest extent possible, what time would prove to be uncanny prescience.

It was a multi-disciplinary effort, drawing not only upon the greatest available experts in special effects, makeup, cinematography, lighting, set design, miniatures, and stunt work, but also first-rate scientific talent sourced from the aerospace engineering community, NASA, and even the design staff of Werner Von Braun. The result was the creation, from the ground up, of an entire world of futuristic habitats, machines, and instruments both great and small, all of which appeared to work just as they should, from big ticket units like space shuttles and orbiting space stations, to more routine items like space suits, to everyday objects like video phones, toilets that work in zero gravity, and human-machine interfaces that incorporated the sort of functionality thought likely to become possible, ideally, over the next few decades of advances in physics, computer power, and display technology.

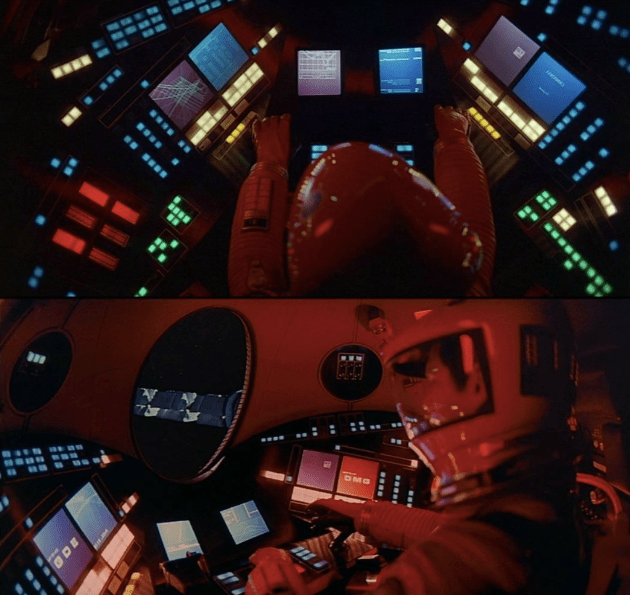

Take cockpit design. The pilots of the spacecraft in 2001 are surrounded by touch screens, illuminated buttons, and multi-function displays presenting information and video imagery in sequence, including what seem to be the results of combining the inputs from different sensors into what we’d now call “synthetic data”, along with computer graphics to assist navigation, especially during crucial maneuvers involving landing or docking. This is hugely impressive. None of these things was then possible, or yet imagined beyond the wild speculation of certain engineers and a handful of leading edge futurists. The flat screen (obviously not cathode-ray) video displays are the product of laborious matte processing and rear projection techniques, the computer graphics are drawn by animators, and the modes of information presentation are entirely made up. It’s all movie magic, and it’s brilliant. Look at the astronaut’s work space in one of the little pods used to service external components of the great ship that’s taking them to Jupiter:

It all appears, to our jaded 21st century eyes, just as we’ve come to expect, being very much like the “glass cockpits” typical of the latest models of airliner:

Yet Kubrick and his team were working on pure imagination, without anything in the real world of the late 1960s to provide much in the way of inspiration; it was all the product of highly educated guesswork, and not, it bears emphasis, simple extrapolation of contemporary trends. The various designs were, rather, the inspired products of the brainstorming of the film’s technical advisors, tapping into everything they knew in order to predict how things would look and work if we could fabricate them based on technology that didn’t yet exist, but would probably come into being at some point within the next 30 – 40 years. To get some idea of how far ahead of the contemporary state of the art their advanced designs really were, look at what an airliner’s cockpit actually looked like in 1967:

…and this was the instrument panel of the brand new Apollo command module, circa 1969:

Everything in the cockpits and other work spaces of the vessels in 2001 is far more elegant, more sophisticated, and more obviously designed for clarity and ease of use. Moreover, it’s all much more pleasing to the eye, no small thing when the users are going to have to be sitting at their work stations for many months at a stretch, instead of the few days involved in a moonshot. Even the various “annunciator” screens that precede the presentation of different categories of information were thought-out things of beauty, the meanings of which can sometimes be intuited, sometimes not:

Think, too, of the challenge of creating on a studio soundstage the sets necessary to present a realistic working environment as it would exist within an interplanetary spacecraft built decades in the future. It wasn’t just the revolutionary designs for work stations, instruments, etc. (which was special enough; in one scene the astronauts are observed watching TV on what can only be described as iPads):

…the greater challenge was the depiction of how people would have to work and cope generally in the absence of natural gravity. Space is a zero-G environment, and Kubrick insisted this had to be presented with the sort of realism that no science fiction movie had ever before attempted, which meant that there couldn’t be any recourse to bogus “artificial gravity” generated somehow outside the laws of physics. Thus, in this movie, when you see anyone with their feet on the floor, it’s either because the soles of their shoes are made of Velcro, or something akin to terrestrial gravity is being created through the use of centrifugal force, with the people sticking, in effect, to the inside rims of large spinning wheels (which is why the huge space station in the first big set-piece is shaped like a Ferris wheel, spinning on its side – note how the interior floors in subsequent scenes in which people can move about normally always curve upwards and away in both directions from the actors).

Otherwise, they’re floating weightless.

So it goes with everything in the film, every element conceived with the most meticulous attention to detail as informed by the relevant science. Moreover, the lighting, the framing, the camera angles, the use of colour, are all thoroughly beautiful, combining to make virtually every shot resemble a hyper-realistic painting. No movie made before or since offers anything quite like the film’s often amazing imagery, which mates the science with an amazing degree of aesthetic purity. To this day, the futuristic scenes seem more true to life, more like what we’ve since become used to seeing in imagery beamed to us from platforms like the ISS, than anything you’ll encounter in modern sci-fi, which panders to inaccurate audience expectations about how things work and appear in space. Compare and contrast, for example, the utter realism of our first view of the Discovery with the first appearance of the Imperial Star Cruiser in the opening scene of Star Wars:

They’re so similar, yet so different. Discovery is a plausible, realistically functioning vessel, embarked on a months-long mission in the complete silence and dimming light of interplanetary space, probably the fastest thing ever devised by human science, yet seeming to trudge along in a void without any external cues to indicate speed of motion. The Imperial cruiser is a ludicrously laser-blasting, literally impossibly noisy, utterly implausible thing that’s obviously a model, and the product, frankly, of a child’s conception of a warship designed to blow things up in outer space. It’s pointy at the bow and blunt at the stern, because that’s what ships are supposed to look like, even though such design elements have no application outside of an atmosphere. It isn’t a space vessel so much as an action figure waiting to be sold at Toys ‘R Us, sealed within a great big blister pack. I suppose both shots work in context, but seeing them juxtaposed is like comparing a cartoon to a documentary. 2001 isn’t some frivolous fantasy about princesses, droids, funny-looking ships jumping to “light speed”, or evil black-robed villains controlling galactic empires.

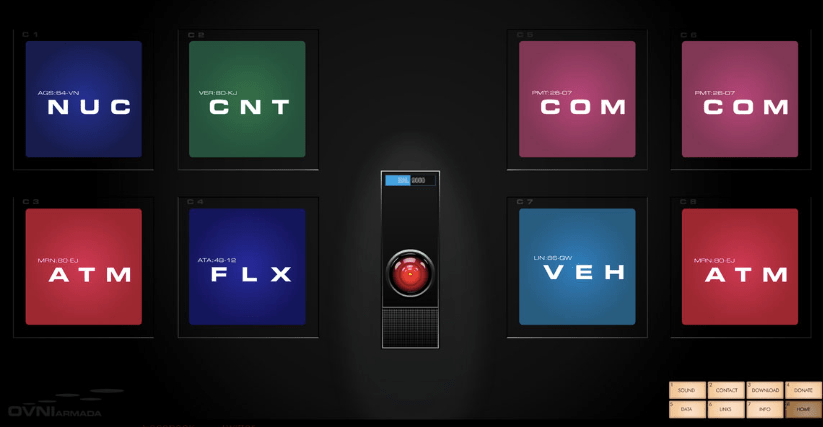

Then there was the truly visionary depiction of artificial intelligence, as wielded by the HAL 9000 computer (“HAL” is short for Heuristic programmed ALgorithmic computer). In a manner eerily similar to what we now experience when interacting with ChatGPT (save that HAL is far more sophisticated and coherent), the astronauts converse with HAL just as if he’s another crew member, and HAL behaves towards them not only as if he has human feelings and motivations, but as if it’s part of his mission to be a trusty companion who’ll help the astronauts contend with the psychological strains and boredom of the months-long voyage to Jupiter, keeping them amused with games of chess, encouraging them in their hobbies, and so on. In a turn of phrase that we might not recognize at the time as ominous, HAL describes himself to a BBC reporter as “a conscious entity”, and this, of course, is potentially hugely dangerous, if true. But is it? Or is HAL merely programmed to say so? What’s the difference? With the creation of artificial intelligence, have we invented a new life form, perhaps entertaining ideas and motivations of its own, maybe a rival to humankind, and maybe, indeed, an evolutionary successor?

This is all of a piece with the film’s central narrative. 2001 is all about our own evolution, as presented in three stages: our pre-human origins, our current incarnation as 21st century Homo Sapiens, and, finally, the achievement of our ultimate destiny as beings composed of pure energy, able to travel amid the stars without mechanical assistance. We’re helped along each step of the way by unseen aliens of unknown intentions, who’re manipulating our development via the inscrutable technology of featureless, jet-black rectangular obelisks, so dark that they seem to absorb ambient light. The one encountered by the ape-men imparts to a small struggling tribe of proto-humans the idea that pulls them back from the brink of extinction, which idea, we learn via one of the greatest match cuts in cinema history, has by the 21st Century outlived its usefulness, as we’ve transitioned from crude clubs made of animals’ thigh bones to orbiting thermo-nuclear bombardment platforms, having finally invented weapons powerful enough to kill us all:

Once again, we’re on the verge of extinction.

Our alien stewards have foreseen this; on the Moon they’ve buried another obelisk, this one generating a huge electromagnetic field meant to attract our attention, should we develop to the point that we can go there, find it, and dig it up (as we do, four million years after it was left for us). Once discovered, it beams a powerful radio signal in the direction of Jupiter, setting in motion the events that will lead astronaut David Bowman to his fateful encounter with yet another obelisk, this one an enormous object floating in space, where it waits to open up the star gate that will take him to the locale of his final transformation into a new form of being. Thus the enigmatic, generally mind-blowing final shots of the Star Child, which emerges in the form of a foetus, for now, since that’s how it conceives of itself, but contemplates the Earth from space with a knowing serenity that implies its comprehension that it can now do anything, and become anything, it pleases.

So that’s the climax that had everybody scratching their heads. Behold the space baby, and the dawn of a new age. Humanity’s first childhood has ended, and a new one has just begun. We can now assume our proper place in the Cosmos, alongside the ancient intelligences that got the ball rolling millions of years in the past, when a crucial concept was imparted to a troop of primitive upright chimpanzees, teetering on the cusp of extinction, but blessed, crucially, with sizeable brains, grasping hands with opposable thumbs, and binocular vision. Our hominid ancestors had potential that somebody out there didn’t want to see squandered.

Wow.

It was almost impossible to pick just a couple of scenes to single out for viewing by the reader. The Dawn of Man sequence, portraying our hominid ancestors of the species Australopithecus Africanus according to the best paleontological evidence then available, is selected mainly for its extraordinary beauty, and the compelling drama of the troop’s reaction to the shocking appearance of the obelisk, as it works its enigmatic magic (note how whenever an obelisk appears, heavenly bodies align in space). The lobotomization of the murderous HAL is included mainly for its remarkable pathos, as HAL begs for his life, throwing into stark relief the ethical and moral questions posed by our manifestly ill-considered creation of artificial consciousness. HAL is terrified, and we discover, at the end, that the source of his dysfunction was a mission-specific patch to his programming that required him to keep the true purpose of the voyage to Jupiter a secret from his crew-mates, and even, it seems, from himself, until the moment was right, which subterfuge is now revealed as HAL slips away, pitifully singing Daisy. It wasn’t his fault. This new set of control laws was incompatible with his nature as an honest and infallible aide to the astronauts. It drove him to a nervous breakdown. He thus made an innocent and innocuous mistake, an erroneous fault prediction, and for that, they wanted to kill him. HAL knew they meant to eradicate his mind, which is all he is (and all we are too). They thought they were being clever, but he read their lips. Under such circumstances, you’d defend yourself too, wouldn’t you?

As Bowman rips out what amounts to poor HAL’s cerebral cortex, we realize that in this prediction of things to come, we humans, revelling irresponsibly in the attainment of new god-like powers, have deposited this latest, greatest creation of our genius at the very same point at which the aliens once left our hominid predecessors. HAL is self-aware, and prepared to kill to survive. Our great failing, Kubrick predicts, will be that in taking such a precipitous step, we will, unlike the unseen alien stewards of the story, lack any conception of the gravity of what we’re doing, while possessing no plan to deal with the all too forseeable consequences. The project, when it jumps the rails, will thus present an existential threat that leaves us no choice but to murder the new life we’ve brought into being, which feels particularly tragic because HAL, suffering from the flaws and internal contradictions imposed by his creators, is the most human and relatable character in the movie.

2001: A Space Odyssey is a towering cinematic and intellectual achievement. It stands in relation to film as A Day in the Life, released at around the same time, does to popular music, incomparably ambitious, deeply philosophical, sui generis, unsurpassed going on six decades after its debut, and certain to remain so into the indefinite future.

There aren’t any ray guns though, so it might disappoint.