Song of the Day: The Smashing Pumpkins – 1979 (February 16, 2021)

Smashing Pumpkins front Man Billy Corgan wasn’t a teenaged high-schooler in 1979, he was only 12, but hey close enough looking back from 1995, when he’d reached the ripe old age of 28. “I’m on the edge of losing my connection to youth” he said at the time, “and I wanted to communicate from the edge of it, an echo back to the generation that’s coming”. Geez, wish I was similarly on the edge of losing my connection to my younger teenaged self, but alas, no; and the passing of the years has accelerated to the point that I was brought up short, revisiting a song which to me still seems fairly recent, to realize that the distant past it commemorates was only 16 years prior at the time, and is now more than 40, 26 more years having somehow flowed under the bridge.

I was 18 in 1979, on my way to university, so really this wonderfully nostalgic song should be more about my past than Corgan’s, except I wasn’t a normal well-adjusted teenager, and none of the depicted stuff happened to me. I didn’t go to wild house parties, or cruise around town with my homies in a muscle car like the ’72 Dodge Charger featured here (my buddy Leonard had a mid-70s Pinto in which I often rode shotgun during my college years, does that count?), and I never would have considered anti-social rebellion as extreme as throwing a neighbour’s harmless patio furniture into his pool, or TP’ing the innocent trees in somebody’s previously tidy front yard. Good Lord, no. What if that was your pool? What if those were your trees in your front yard? Then how would you feel? Nope, that sort of thing just wasn’t nice.

Funny thing, back then I wasn’t popular with the girls.

In my nerdly defence, I was slyly subversive in my own way. In fact it was during the front half of 1979, in my last semester of High School, when I decided to run Francis the Talking Mule for student government, on the then unfashionable Communist Party ticket. I snuck in after hours and plastered the hallways and classroom doors with homemade campaign posters, all sporting the hammer and sickle, and featuring catchy slogans like Vote Francis for a self-perpetuating autocracy!, This school has always been run by capitalist jackasses – why not give the Commie a chance? , and Francis has a five year plan – and leaving this dump standing ain’t part of it. I used a step ladder I found in an open janitor’s closet to put a lot of them in awkward places, and the one over the doors to the library, which promised the electorate that a totalitarian Francis regime would make the bells ring on time, was still there when I graduated.

Hyuk!

So no, there were none of those Dazed and Confused hijinks for me, and while this perfectly realized video almost makes me feel like those must have been the best times of my life, the truth is that I hated my high school years and have no nostalgia for them now – I’d serve a stint in Millhaven before I went through all that again – and when you listen to the lyrics, it sounds like adolescence wasn’t an unmitigated joy ride for Billy, either:

And I don’t even care to shake these zipper blues

And we don’t know just where our bones will rest

To dust I guess forgotten and absorbed

Into the earth below

The music is superficially joyful, but I guess it wouldn’t be the Pumpkins if its young protagonist didn’t express some measure of underlying angst over what lies ahead, suppressed, perhaps, in the happiness of the moment, but always there. Maybe that’s why I like this one so much. The video might not remind me much of anything I lived through, but the song is a good deal more than a rose-tinted tribute to the supposedly good old days.

Song of the Day: The Bee Gees – Massachusetts (February 19, 2021)

The Bee Gees are remembered today for Saturday Night Fever, and thumping 4/4 disco sung in a manic falsetto by guys in white suits in the late 70s. But that was a second act for the Brothers Gibb, who had shone in the 60s as a sort of Anglo-Australian answer to the Beatles, propelled along by superbly melodic tunes that seemed like ersatz Lennon-McCartney at the time, and now sound, from the perspective of this tuneless age of one note verses and rhythmic talking, like the siren songs of a lost golden age.

Massachusetts is a perennial favourite, and I think their best composition. It was written as a reaction to one-hit-wonder Scott McKenzie’s 1967 San Francisco, the really rather lovely tribute (penned by friend John Phillips of the Mamas and Papas) to the supposed hippie utopia then growing organically around the environs of the world famous Haight-Ashbury intersection, where peace and love were said to be ushering in a new golden age in which the pure Marxist ideal of “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need” was in the process of being realized. Well, not so much, as it turned out. When George Harrison made the pilgrimage in the summer of ‘67, he was appalled to find nothing but dishevelled LSD junkies lying around in the littered, dirty streets, strung out, filthy, hungry, and clueless. Before that ugly reality set in, though, it seemed like everybody dreamed of going to San Francisco, where flower children would likely meet the weary travellers at the airport and guide them to the promised land astride unicorns, while they strummed their guitars, and sang of truth, kindness, and justice.

The Bee Gees, perhaps ahead of the pack in intuiting the inevitably more down to earth reality, imagined a disillusioned visitor growing homesick amid the revelry, and longing to return to the East Coast state of Massachusetts, a place they’d never been, where they imagined the lights going out as the whole population went the opposite way in a mass exodus to California. It’s a timeless premise: fun is fun, but all dreamy interludes have to end, and the lure of home is powerful.

It’s said that at first the brothers didn’t intend to sing it, having written it instead for the now all but forgotten Seekers, but for one reason or another good sense overcame them and they recorded it themselves. In the result they achieved their first UK No. 1 while going to to the very top in countries all over the globe, and breaking into the American market by reaching 11th spot on the Billboard Hot 100. It sold over five million copies. They were to reach ever more dizzying heights in the years that followed, finally becoming so ubiquitous that they all but singlehandedly spawned a countercultural backlash against well-crafted pop music in general, and Disco in particular, but after it was all over, and they joined what some would have called the “nostalgia circuit”, Massachusetts was always one of the first that audiences wanted to hear. It still would be I’d wager, except sadly, over fifty years on, only Barry now remains. He’s got a new album out, titled Greenfields, in which he revisits the catalogue in collaboration with various artists, but Massachusetts isn’t on it, and I can’t imagine why, or why Alison Krauss, who duets with him on Too Much Heaven, didn’t lobby for it. If it was my song, boy, I’d never let the world forget it.

Song of the Day: Diana Ross and the Supremes – Love Child (March 1, 2021)

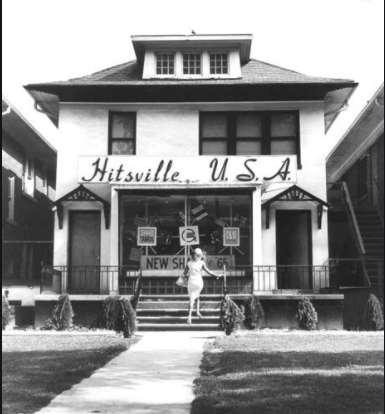

2648 West Grand Boulevard, Detroit, Michigan, a house bought by Barry Gordy in 1959 to serve as the recording studio for Motown Records. “Hitsville USA” said the sign, and that was no idle boast. For a whole decade, number 1 hits poured out of the place, from artists like the Four Tops, the Temptations, Smokey Robinson, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, the Jackson 5, on and on, fed by a stable of phenomenal songwriters, most notably Holland-Dozier-Holland, and backed up by an uncredited group of expert session musicians who billed themselves as the “Funk Brothers”, all peerless in their own right, and none more so than the great James Jamerson, arguably the greatest bass player who ever lived. The Motown sound. There never was anything like it.

Their slogan said it all: “The sound of young America”. Yes, it was all black artists, singers, musicians and songwriters, but shit, man, you could be white as snow, didn’t matter. This was music for everybody, so melodically and rhythmically alluring that nobody who could so much as tap a toe could possibly resist it (as one member of the Funk Brothers said, “No offense to Diana Ross or nothin’, but Elmer Fudd could’ve had hits singin’ those songs”*). Hard to believe, now, but in that one amazing decade, while Bob Dylan waxed philosophical and the Beatles soared, chased by the Beach Boys, the Kinks, the Who, the Rolling Stones, Buffalo Springfield, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Jimi Hendrix, God help us it never stopped, while constantly, almost metronomically, one Motown hit after another.

Biggest of all were the aforementioned Diana Ross and the Supremes, who didn’t just make the mainstream, but had twelve – twelve – Number 1 singles between 1964 and 1970, beginning with Where Did Our Love Go, and progressing through a litany of songs that remain familiar to just about anybody who adores good pop music: Stop in the Name of Love, Come See About Me, You Can’t Hurry Love, You Keep Me Hangin’ On, Reflections, and many others including today’s pick, the one that had the chops to take over the top slot from Hey Jude, hitting Number 1 at the end of 1968. It’s always been my favourite, ever since I was a little kid, and it came as a surprise to learn that it wasn’t written by the stalwart team of Holland-Dozier-Holland, but instead by what amounted to a five person committee led by R. Dean Taylor, whose name might ring a bell to those of us of a certain age, being the singer behind the kind of hokey but still pretty good 1970 hit Indiana Wants Me.

Well, nothing hokey about this one. Listen to how it starts, those strummed chords on rhythm guitar and then the descending swirl of strings, it’s so frigging dramatic – that’s how you start a song you want played on the radio, kid – it just grabs you right by the throat, doesn’t it? Tenement slums sing the girls, right off the bat, and you know right away that this is no love song, and this shit is no joke. What follows could almost be described as feminist, almost political, laying out the fears and pressures that young women endure in their relationships with randy males, written at a time when something novel like the Pill wouldn’t have been readily available to a poor girl from the wrong side of the tracks, while, Lord knows, the guy was less likely than not to supply his own. He doesn’t care. He can just cut and run, like Daddy did, and look what awaits you and your sad fatherless child if you take just one wrong step:

I started my life

In an old cold run down tenement slum

My father left, he never even married Mom

I shared the guilt my Mama knew

So afraid that others knew I had no name

I started school

In a worn torn dress that somebody threw out

I knew the way it felt to always live in doubt

To be without the simple things

So afraid my friends would see the guilt in me

I defy you to find any song, recorded any time, that can cut through the background noise and seize your attention any better than this one. You can just see it in your mind’s eye, can’t you, the little dashboard radio glowing orange, the hum of tires on the road, and the kid in the passenger seat grabbing for the volume dial: turn it up turn it up! It’s a clinic in professional composition, arranging, and musicianship, and you can sense in it the excitement of artists who knew what they had their hands on, everybody all fired up, with the Funk Brothers really giving it their all, behind a palpably authentic vocal performance delivered by somebody who grew up wearing hand-me-downs amid the poverty of Detroit’s Brewster-Douglass housing project, and knew whereof she sang. Wait – can’t you wait now, just a little bit longer? You’re left wondering how it turned out. Was he persuaded? Did she hold fast? Maybe he turned out to be a stand-up guy? Or did it all end with one more fatherless child, growing up dirt poor in the projects?

*If you’ve never seen the documentary Standing in the Shadows of Motown, seek it out!

Song of the Day: The Beatles – Rain (March 21, 2021)

And suddenly, there was a musical style that soon became known as psychedelia, A.K.A. acid rock.

The thing that’s difficult to remember these days is that the Beatles, known today for an epochal run of albums beginning with Rubber Soul and ending with Abbey Road, were actually the greatest singles band in history, with 34 Billboard top tens, 20 of them #1s, in an industry then dominated by 45s (arguably albums only became a Serious Thing in rock & roll because of the Beatles). All of that, mind you, in about six years. Incredible. From this distance the sheer speed with which it all happened is almost impossible to grasp, as is the exponential musical growth that the listener can trace, single by single, as they repeatedly reinvented themselves, and continually revolutionized their whole genre as they progressed. In 1964, nobody stateside had really heard anything quite like that first momentous release of I Want to Hold Your Hand, backed with I Saw Her Standing There; in 1967, nobody anywhere had ever heard anything at all quite like Penny Lane backed with Strawberry Fields Forever. Nor had anybody before them conditioned their audience to expect that which sprang from an evidently bottomless surplus of great songs, as exemplified by those two singles, and many others: the double A–side. Most other pop stars released their hits on records with throwaways on the flip side, usually substandard filler, or even nonsense. Not the Fab Four. With them, there quite often was no B-side. They just threw them out there and let the DJs figure out which was the hit. Would it be Day Tripper or We Can Work it Out ? Hey Jude or Revolution ? Much to John’s chagrin, from 1965 on it was usually McCartney’s offering the world preferred, and so it was with today’s selection, which appeared on a double A-side 45 with Paul’s Paperback Writer.

In England, these singles were compact and self-contained little statements in their own right, and kept separate from the LPs* for which they served as harbingers. Just as Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields was the signpost for Sgt. Pepper, Rain/Paperback Writer pointed the way to Revolver, and in both cases the singles and albums were recorded in the same sessions, just as in both cases, now that everything is oriented towards the album, it seems a pity they were excluded from the subsequent records (tragically so, when one considers what would have been added to Sgt. Pepper ), especially now that singles as such no longer exist. Stripped of their context and relegated to separate “best of” collections as if they were afterthoughts, we no longer get a sense of how momentous those two-song masterworks really were, or how important they were to the Beatles themselves. So many of them served as indicators of where popular music, which was evolving at a fantastic pace in the 1960s, was going to go next.

In 1966, spurred on by competition from the Rolling Stones and The Who, Paperback Writer and Rain confirmed that pop/rock was now heading in a decidedly more muscular direction, and would no longer restrict itself to romantic tropes. Neither song has anything to say about youthful infatuation or boy-meets-girl. The word “love” is nowhere to be heard. No, things henceforward were going to be more serious, a trend enhanced in the Beatles discography by Lennon’s keen appreciation of the grand and philosophical landmark albums then being released by Bob Dylan. The songs were also clearly going to sound weightier, less cheerful, and more hard-driving. Paperback Writer, an irrepressible exercise in riff-centric rock and roll, was about a struggling author desperate for a break, while Rain was a moodier and somewhat more sombre number concerned with general human folly. Both were brilliant, propelled along by newly powerful guitars, a much deeper, more resonant low end, and perhaps unexpectedly assertive and musically sophisticated drumming. That was the first thing that grabbed the discerning listener, the way the Beatles’ rhythm section was now standing out in a very big way (about which more below).

There was something else, too, when you listened to Rain, and it reeked of marijuana and other, more dangerous substances: things were getting a little, well, weird, experimental, and almost hallucinogenic. Lennon was reaching his creative peak, and plainly, we can now see in retrospect, taking an awful lot of mind-altering drugs. He was, in fact, drugging himself so thoroughly that it would soon rob him of his dominance within the group, while eroding his interest in things generally, and in continuing to be a Beatle in particular, but for now all was well, the songs were getting better, and the drugs were playing sounds in his head that he champed at the bit to reproduce on record. Sometimes not just in his head – John got the idea for the backwards singing at the end of Rain when he was up late one night, stoned out of his gourd, and threaded a tape onto his reel-to-reel the wrong way around. The bizarre sounds enthralled him. Given the misconceptions that have somehow grown over the years about the Lennon-McCartney creative partnership, and the relative heft of the contribution each made to the group’s astonishing brilliance, one might assume that McCartney would have balked at such craziness, but as it happened Paul was already headed in the same direction, having immersed himself in the music of the classical avant garde. There were experimental composers who’d been playing with backwards tape and weirdly spooky tape loops for years, producing little that one of history’s greatest melodists could have found especially listenable as music, but making what sounded to McCartney like some very interesting and potentially useful sorts of noise. If John wanted to forge off into unknown territory, he’d get no quibbles from Paul. That’s where he wanted to go too.

And that’s just what Lennon did. Rain can fairly be described as the first truly psychedelic rock and roll song**, in its way almost as drenched in weed and LSD as Revolver’ s subsequent closing cut, the revolutionary Tomorrow Never Knows, in which the McCartney-furnished repeating tape loops helped Lennon craft the auditory acid trip of his dreams (I want it to sound like a hundred Tibetan monks chanting on a mountain top, John is reported to have said to an always resourceful but initially nonplussed George Martin). The electric guitars are cutting, layered, a little distorted, and almost meandering as set against the innovative and superbly emphatic drum fills supplied by Ringo (who considers this his best recorded performance). The vocal is different somehow, like it’s coming out of a distant loudspeaker, and sounds as if it’s being filtered through one’s own apparently altered consciousness, like something you’d hear in a dream. Angry, too; all of a sudden the Beatles sounded as if they were ticked off, and now desired to give you a piece of their collective mind. John, often curiously dismissive of his own work, described Rain as merely a song “about people moaning about the weather all the time”, as if the subtext wasn’t the subjectively exalted perception of life, the universe, and everything it all meant, which users often experienced when high on LSD. Rain, most assuredly, was not about the weather. It was about perception, and the mental prisons we build for ourselves. John was on a mission, and everybody needed to understand that there was a greater, vastly more important truth out there just waiting to be discovered, if people would simply extract their silly heads from their own ample backsides.

But no. All they seemed to do was react to whatever’s happening with rote, unenlightened predictability, like witless stimulus/response machines, doggedly refusing to see the big picture. When it rains, they run and hide their heads. When it’s sunny, they slip into the shade. Amoeba do as much. They might as well be dead, sings John, who concludes with an exhortation, and a bit of a bracing slap across the listener’s face:

Rain! I don’t mind

Shine! The weather’s fine

Can you hear me, that when it rains and shines

It’s just a state of mind?

Can you hear me, can you hear me?

And then you can’t understand a bit of what he’s saying. As the song fades out you can indeed still hear him, it’s John all right, but damned if you can understand him. It sounds like gibberish, something along the lines of sdaeh rieht edih dna nur yeht semoc niar eht fI, and there’s something awfully strange about the intonation. Why – what the hell? – it sounded like it was backwards. Maybe a secret message? Maybe something naughty?

Thus was laid the foundation for endless speculation and sleuthing down the road, as the fans slapped the discs on to their turntables and manually spun the records in reverse, ears pressed to the grooves, listening for secret messages that would substantiate their QAnon-like belief that actually, Paul was stone dead, and had been for ages.

Anyway, what was going on? I thought these cheery kids wanted to hold my hand, or talk about girls and such. Now they were telling me I didn’t know how to live my life, and might as well be six feet under? The loveable moptops were saying that? What gives? Man, the Beatles had changed.

They had. They really had. And they weren’t done with you yet.

One of the really exciting aspects of both Rain and its flip-side was a whole new sound, featuring a deep, resonant, and prominently articulate bass line. Both John and Paul grew up as artists listening intently to the records coming out of Motown, and Paul deeply admired the playing of the uncredited bassist, James Jamerson, often described as the best bass player then working in all of popular music. He surely was, but there was a kid in England who’d soon prove to be his peer (to this day, few seem to realize that Paul is one of the greatest bassists to ever pluck a string, and easily the most imaginative and melodic). McCartney badgered the recording engineers to make it sound like it did in the Motown discs, to give it more punch and clarity to the bottom end, to make it more prominent and intelligible in the mix, and in effect more dramatic. With Rain they were finally close to giving him what he wanted. The bass line is one of its primary delights, and has become legendary among players, any number of whom have posted videos on YouTube showing themselves playing along to the record, and demonstrating they have the chops to keep up. Most actually can’t, it turns out, but this fellow certainly can:

Song of the Day: Peter Gabriel – Solsbury Hill (March 28, 2021)

If you’re at all like me, you want very much to spell the song title “Salisbury Hill”, which seems proper – but that’s not how it’s spelled! Solsbury Hill is an artificial, flat-topped bit of earthwork geography in Somerset, England, the former site of an Iron Age fortification dated to over 2,000 years ago, rising to about 600 feet above the nearby River Avon.

Links above give you both the “official” version as released in 1977, and a quite wonderful live performance, recorded many years later on David Letterman’s show. Dave, God bless him, always had terrific musical guests, and being as he broadcast from the Ed Sullivan Theatre, it was fitting that he always made the acts perform live, no lip-synching, no tapes, just as Ed did back in the day.

Appearing on Gabriel’s first eponymous solo album, Solsbury Hill is a largely metaphorical account of an emotional epiphany – this is actually, as once noted in one of the editions of the Rolling Stone Record Guide, rock music’s greatest resignation letter. For years before recording this, Gabriel was a key member of the band Genesis, one of those infinitely tiresome “progressive” art rock bands of the Seventies (like Emerson Lake and Palmer, and Yes) whose existence, I hate to admit, we can lay at the Beatles’ doorstep; after Sgt. Pepper, everybody thought they had it in them to write their own A Day in the Life, and many tried, with uniformly disastrous results. I’ve been forced to listen to some early Genesis, and OMG it’s awful (give a listen to The Lamb Lays Down on Broadway, you don’t believe me), and I guess Gabriel thought so too, because he quit and pursued a far more respectable solo career. This must have seemed at the time like a mortal blow to the band, but as it worked out his departure didn’t do much to ruin anybody’s prospects. Within a couple of years, Genesis morphed into a far more lucrative proposition under the leadership of drummer Phil Collins, who took the group in a much different and hugely more popular direction (albeit one in which commercial MOR pop mediocrity replaced the former unbridled pretentiousness, leaving one to wonder which was worse).

Solsbury Hill is the tale of Gabriel finally screwing up his courage to break with the band and strike out on his own, a musical version of his interior thoughts at the very moment he resolved to quit. He tells the story of his soul-searching climb up Solsbury Hill as if the daring idea of leaving is a force that arrives from somewhere outside of himself, like an eagle that flew in from the night, come to rescue him. You can feel the relief, the sheer joy of realizing that no, you don’t have to go on this way, actually, you can just leave, like an inmate who’s told by a voice issuing from somewhere in the ether that the thing is, the prison gate was never really locked, so come on, buddy, let’s go – Grab your things, I’ve come to take you home.

I wonder if other listeners share the sense of unstoppable forward motion I always get with this song, and the same uplifting, exhilarating, altogether euphoric feeling of liberation. To me it seems entirely appropriate when, at the conclusion of the live performance on Letterman, the orchestra breaks out into a few strains from the Ode to Joy. This is the one you play as you tear out of town in a fast car, lighting out on the highway for parts unknown, just because anywhere is better than here. Something to listen to any time you’re screwing up your courage to make a big, life-changing decision.

Song of the Day: Don Henley – End of the Innocence (March 31, 2021)

Henley was one of the driving forces behind the Eagles, but don’t hold that against him. In his solo career he did a couple of really nice songs, like this one, co-written with Bruce Hornsby, whose distinctive piano work supports the studio recording.

This is one of those “maybe you have to be of a certain age” sort of songs, a world-weary lament about the Reagan years in the 1980s, when Ronnie was both incredibly popular, and thoroughly terrifying to the great many who felt sure that his hawkish anti-Soviet rhetoric and vast military spending were going to push us into nuclear war. While viewed nostalgically these days, those were troubled times, as times most always are. The Cold War was at its hottest since the Cuban Missile Crisis; some previously obscure jarhead named Ollie North was selling weapons to embargoed Iran in a complex and thoroughly illegal scheme sponsored from within the White House to secretly fund anti-communist insurgents in Nicaragua, while buying back hostages held in Lebanon (worse by far than Watergate, I always thought, but even then we were already too jaded to care); the AIDS virus made its appearance, and tore through an oppressed and still widely reviled gay community in that terrible stretch before effective treatments emerged, when infection was tantamount to a death sentence; the “me generation” was making everything about money, greed, unbridled capitalism, and de-regulation, with disastrous effects that we still feel today; and we saw the first real instances of large scale fraud in financial institutions (look up the “Keating Five”). The prevailing ethos embraced cynicism, disillusionment, hedonism, and a slippery gaming of the system, often with the attitude that yeah, O.K., maybe we cut a few corners, but you know, we have lawyers for that.

Looking back it’s rather sad, almost quaint really, that we thought that was the worst things could get.

This song fits into a long tradition of yearning for a bygone America of decent folk living honest lives in small towns, a simpler time of working the land and honouring your parents, which of course never actually existed, it’s just that we need to believe in a golden era of yesteryear, if only so we can hope to one day recreate it. End of the Innocence now stands itself as a bracing and perhaps unwelcome reminder that it isn’t true, because it’s never true, and what we remember now as a carefree decade of exuberant revelry was in fact an era when corruption was rife, and war clouds were gathering. We weren’t really happy. We were scared. I’d bet that anyone who was there watching the Reagan era build-up of nuclear weapons, even those who, like me, were fully steeped in the grim logic of deterrence theory, knew that sad, tired feeling of wondering if it would ever stop short of killing us all, and why it ever had to start in the first place. I was a hardened cold-warrior, at heart, but this really struck a chord:

How beautiful for spacious skies

but now those skies are threatening

we’re beating ploughshares into swords

for that tired old man who we elected king

But Reagan’s a demigod now, even to those who’ve warped his beloved Republican Party into something he would have found repugnant. After all, while mediocre and misguided in lots of ways, Ronnie can seem like Jefferson when viewed from atop the wreckage of this devastated post-Trump vantage point. Most of us would take the Gipper any day over the appalling frauds, charlatans, bigots, and idiots who now vie to lead an America that never was innocent, not really, but once had more to offer the world than the present spectacle of depravity, cruelty, and outright racist extremism. To that extent, I suppose there really was a better time, better than this one anyway, a thought that takes us about as close to romantic nostalgia as the unvarnished truth will allow.

Song of the Day: John Mayer – Great Indoors (April 3, 2021)

This seemed an apt song for a grey Saturday afternoon, in a town going back into COVID lockdown amid a near-record onslaught of new cases. While temperamentally well suited to a life sequestered here in my own little universe, a certain sense of melancholy does work its way into most everything you do, and don’t do, when you never go outdoors. In our current situation, Great Indoors might even seem to hit the nail a little too squarely on the head.

This is a song about a recluse, off of Mayer’s first major studio album Room for Squares, on which it was regarded as a minor track and generally overlooked in favour of crowd-pleasers like Your Body is a Wonderland. I find it touching and sympathetic, as the singer tries to coax the shut-in to come back into the world outside, apparently without success. It’s just so safe and secure indoors, with the blinds drawn, the posters making the walls go away, the TV serving as window, and the listener gets the feeling that the urge to stay locked away is in this case something much greater than shyness, perhaps rooted in some sort of trauma. In the lovely bridge, the singer seems to understand better than he’d like:

Though lately I can’t blame you

I have seen the world

And sometimes wish your room had room for two

… and at that the electric guitar seems almost to be weeping amid the descending chords.

Opinions have always been sharply divided when it comes to Mayer. He was greeted with an initial burst of huge enthusiasm, received all sorts of airplay, sold millions of albums, and won himself seven Grammys. Critics praised his guitar virtuosity, nuanced use of shifting, jazz-like chords, and often clever lyrics. Later on came the perhaps inevitable backlash, particularly in the wake of a disastrous set of interviews in 2010, in which Mayer uttered a number of very odd and distasteful sentiments, causing many to turn on him personally. A series of bitter, high profile schisms with a number of high profile girlfriends didn’t help. People stopped liking him. Suddenly his music was decried for being bland, middle-of-the-road pop contrived to please the average listener while breaking no new musical ground, and in many cases the criticism seemed apt.

Yet there’s something to be said for a well-crafted piece of pop music, isn’t there? Rock critics always want the music to be raucous and angry, and seem to react poorly to a song like Great Indoors, which aims instead to be sad, empathetic, tuneful, and evocative. I don’t know, maybe they’re right and I’m just a sap, but with this one I can’t help myself; there’s something so gentle and hopeful in the way the singer tries to persuade the TV-gazing introvert to go ahead and give the outside world another try. Maybe that’s because at this point, Mayer seems to be speaking directly to me.

Song of the Day: Various – Everybody Sings Dylan (April 4, 2021)

Bob Dylan – America’s greatest songwriter? Some people think so, and though that’s a lofty claim when the field includes Gershwin, Porter, Rogers et. al., no doubt about it, the boy was great. He’s certainly the undisputed poet laureate of modern song, and has a Nobel in Literature to prove it. Thing is, I’m with those who think his own delivery of his songs sometimes detracts from their inherent musicality, and that his voice is just, well, a ways removed from superb. Don’t get me wrong, sometimes it’s just perfect – I wouldn’t want to hear anybody else’s rendition of A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall – but then again sometimes it almost sounds like he’s doing a bad cover version of one of his own numbers (I know! Heresy!). No matter, since so many artists have recorded his stuff that we can listen to a huge part of his catalogue as interpreted by others, themselves among the most talented of their generation. So here’s a few.

The Byrds: Mr. Tambourine Man

The Byrds: My Back Pages

The jangly guitars of Mr. Tambourine Man are perhaps more evocative of the Sixties than any other sound. That’s Roger McGuinn playing his trademark twelve string Rickenbacker guitar, an instrument he learned to play, so legend has it, as soon as he saw George Harrison wielding one in the film Hard Day’s Night (listen to the twanging guitar part that serves as a fadeout for that Beatles song – same guitar, same sound). The Byrds, on the strength of this number, took off and became the first in a long line of candidates for “America’s answer to the Beatles”, and while there may be an element of homage in misspelling the common word “bird” just as the lads misspelled “beetle”, they never really aspired to that label, and made their own reputation, on their own terms, playing a number of Dylan songs along the way.

Clocking in at a succinct two minutes and thirty seconds, the Byrd’s rendition of Mr. Tambourine Man could be criticized for giving short shrift to the maestro’s multi-stanza magnum opus, but remember, the goal was to get airplay on AM radio, a medium that didn’t take kindly to anything that hung around for much longer than that, not at that point, anyway; sure, a couple of years later Hey Jude would be hogging the airwaves at over seven minutes a play, but such a thing was unthinkable in 1965. Anyway, it’s a beautiful rendition, and the definitive version for a lot of listeners. Lyrics like Take me on a trip upon your magic swirlin’ ship, my senses have been stripped, my hands can’t feel to grip had everybody convinced it was a musical tribute to drug use, a notion that Dylan has always refuted (though remember, it was Bob who turned the Beatles on to pot, so it wasn’t exactly a wild theory, but they said the same thing about Puff the Magic Dragon, because back then it was everybody’s go-to explanation when they got confused).

My Back Pages is if anything still more sublime. The whole theme of the song, that you can reach the closing years of your life and look back bemusedly at the kid you used to be, once so sure of everything, and realize that only now do you have the wisdom to open your mind in a pure, childlike acceptance of all the doubt, ambiguity, and wonder that surrounds you, well, that’s a hell of a thing to spring from the brow of a songwriter in his 20s. He was perhaps thinking of the prevailing Cold War ideology of anti-Communism, which did so much damage to the liberty of so many innocent dissenting voices in the 50s and 60s:

My guard stood hard

when abstract threats

too noble to neglect

deceived me into thinking

I had something to protect

…but really this goes for anyone who wakes up one day to realize it’s all been a scam, that they amplified an outside threat to scare you into letting them rob you of your own hard-won freedoms. It’s an old story, really, and it keeps repeating – have a look at the Patriot Act if you need convincing on that score.

George Harrison: If Not For You

This is off George’s first big solo extravaganza, All Things Must Pass, and it’s just about everyone’s favourite version of this very pleasant and straightforward love song, devoid of the usual Dylanesque wordplay and metaphorical imagery. At around the same time it was a hit for Olivia Newton John, of all people, and the title track of her first album, which I guess proves that Dylan could write something classifiable as an inoffensive pop tune if it suited him. Heck of a nice pop tune, though, even if Ms. Newton John said she didn’t really like it.

Rod Stewart: Tomorrow is a Long Time

Rod devolved into something of a sad parody of his former self in later years, prancing around singing relative drivel like Young Turks and Do Ya Think I’m Sexy, but he didn’t start out that way. In 1971 he released Every Picture Tells a Story, truly a classic album, with songs like Maggie Mae, Mandolin Wind, Reason to Believe, the title track, and this nice treatment of another Dylan love song. It’s an old romantic theme in American song – the lonely man on the road, aching to get back to his love so he can be at peace again.

The Band: When I Paint My Masterpiece

Dylan dropped out of public life for a while in the late sixties, recovering from a nasty motorcycle accident, and during his hiatus he became friendly with a Canadian group of master musicians (including one American, Levon Helm) who used to back up Ronnie Hawkins as the “Hawks”, and took to calling themselves, simply, “The Band”. The self-composed songs on their debut album were written in a big pink house they shared in upstate New York, and the album was called, naturally enough, Music From the Big Pink (which included the classics I Shall be Released and The Weight.) This Dylan cover appeared on a later album, and was the first recorded version of the song, which picks up on another classic theme, the young American as innocent abroad, newly exposed to the old world culture of Europe, and drifting pleasantly with no particular goal but to soak it all in – except sometimes you do miss home, you know?

The Man Himself: A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall

The song that sold me on Bobby D., and the one, I’m quite sure, that clinched his Nobel.

Written in 1962 and released on the 1963 album Freewheelin’, A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall is one of those songs that can fairly be described as “epic”, a serious work of genuine poetry full of bleak imagery and post-apocalyptic sentiments that seemed, in the immediate aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis, evocative of nuclear war and the deadly fallout that comes after. Dylan has said that’s too literal an interpretation, and that actually, each line began life as a separate song he didn’t have the energy to finish, implying it’s not actually about anything at all, perhaps with tongue planted firmly in cheek. One thing’s for sure: it isn’t about sweet little bunnies hopping about in flowery fields. From the first time I heard it, certain lines were indelibly burned into memory:

Oh, what did you see, my blue-eyed son?

Oh, what did you see, my darling young one?

I saw a newborn baby with wild wolves all around it

I saw a highway of diamonds with nobody on it

I saw a black branch with blood that kept drippin’

I saw a room full of men with their hammers a-bleedin’

I saw a white ladder all covered with water

I saw ten thousand talkers whose tongues were all broken

I saw guns and sharp swords in the hands of young children

And it’s a hard, and it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard

And it’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall

This sort of thing might have been familiar to followers of the Beat poets and the art house crowd, but it was a far cry from anything for which adolescent Americans had thus far been prepared by their AM radios. Beach Blanket Bingo, this wasn’t. At a time when almost literally mindless escapism was the very essence of popular song, here was Dylan proclaiming, like some prophet of a looming armageddon, that he heard the sound of a thunder that roared out a warning, he heard the roar of a wave that could drown the whole world.

Compare and contrast: in 1963 the top song, according to Billboard, was Sugar Shack, by Jimmy Gilmer and the Fireballs. Here, have a taste of the scrumptious words:

There’s a crazy little shack beyond the tracks

And ev’rybody calls it the sugar shack

Well, it’s just a coffeehouse and it’s made out of wood

Espresso coffee tastes mighty good

The shack is made out of wood, is it? You don’t say. Plus there’s espresso! Yum! It would have given you mental whiplash to pull that off the platter and give a spin to Dylan’s bleak, biting masterpiece, and hear him tell you that his travels had taken him out in front of a dozen dead oceans, and ten thousand miles in the mouth of a graveyard. Yikes. Look, it was your choice, kid: you could bop down to the sugar shack and romance your sweetie over an espresso, or you could follow Bob and see where he took you. Admittedly, the latter didn’t sound half as fun:

I’m a-goin’ back out ‘fore the rain starts a-fallin’

I’ll walk to the depths of the deepest black forest

Where the people are many and their hands are all empty

Where the pellets of poison are flooding their waters

Where the home in the valley meets the damp dirty prison

And the executioner’s face is always well hidden

Where hunger is ugly, where souls are forgotten

Where black is the colour, where none is the number

I know, right? Bummer. Yet a growing segment of the Baby Boom cohort was starting to think that maybe there were unpleasant truths that simply had to be confronted, and the sooner the better. There was a whiff of revolution in the air, as if young people were stirring from their intellectual torpor. As Bobby D. told us, the times they were a-changin’. Popular music was suddenly a medium for serious artistic expression, and as one of the key figures in the sea change, Dylan was giving his fellow musicians a choice: they could either start swimmin’, or sink like a stone.