Ben Folds: Annie Waits (December 20, 2021)

In this typically clever and sophisticated piano piece, Folds, a thinking person’s sort of songwriter, presents a poignant story of a girl being stood up on a date, standing alone on some street corner, momentarily hopeful as each new set of headlights crests the hill, only to pass right by, wondering if her absent suitor has had some sort of accident (would that be worse?), and imagining a bleak, lonely future of Friday night bingo and feeding pigeons from park benches. You see?, she thinks to herself during the beautiful, descending bridge, this is why I’d rather be alone. Nobody can break your heart after you’ve finally given up.

Unwanted, or perhaps merely unnoticed, is the narrator, who’d be glad to be the one to stay by her side. Annie waits, but not for him.

The Who: Who Are You (January 1, 2022)

Just a terrific performance of the song that was in many ways The Who’s last great hurrah. Find me a rock ‘n roll number with better opening lines than these:

I woke up in a Soho doorway

A policeman knew my name

He said “You can go sleep at home tonight

If you can get up and walk away”

I staggered back to the underground

And the breeze blew back my hair

I remember throwing punches around

And preaching from my chair

It was the late 1970s. If there’d been any lingering doubt over the ultimate hollowness of the youth-driven cultural transformation of the prior decade, by then it was well and truly buried. Rock had become big business, a pre-fabricated, shrink-wrapped, stadium-filling commercial juggernaut controlled by guys in suits, disco was taking over, the singer-songwriters were running rampant, and AM radio was a dead zone of danceable jingles about amorous muskrats and the frantic shaking of booties. The industry had turned into such a bloated self-parody that mainstream pop music had bred its own counterculture, the punks, determined, so it seemed to Pete Townshend, to scoop the rebel crown out of the gutter. His crown. “It was a revolution”, he said many years later, “and I reckoned the Beatles, the Who and the Stones were going to get their heads cut off in the public square”, and the thing was, he wasn’t sure if he was bitter and envious, or just relieved. Drunk, degenerate, and disillusioned, Pete was flailing.

It was in this already sour frame of mind that Townshend began an intensely demoralizing marathon business meeting in New York – various accounts have it stretching to as many as fourteen hours, but the lyrics make it out to be eleven – struggling with legendary parasite Allen Klein to secure royalties. Working class bandmate Roger Daltry, a former apprentice sheet metal worker, had always been adamant that he wasn’t apologizing to anybody for making it all about money, but Pete had once fancied himself an artist on a much higher mission. So much for that! Later on, he was sitting slit-eyed in some Soho bar, drinking himself stuporous, wondering how it had all come to this, and lamenting what a bunch of f’ing sellouts he and his peers had all turned out to be, when who walks in? Who, here, of all places? None other than Steve Jones and Paul Cook of the Sex Pistols. Christ! The last guys he needed to see. They recognized him straight away, of course, and came right over to join him, so Pete, struggling to thread his feet into the stirrups on his high horse, decided it was past time that the little upstart bastards learned the ugly facts of rock ‘n roll life from somebody who’d already seen and done it all while they were still in bloody short pants, somebody who’d experienced the complete moral, intellectual, philosophical, spiritual, and indeed physical decay that awaited them just down the road, however flush with triumph they might now feel. Executive summary: It’s all shite and kills everyone who touches it, so if you think you’re the ones to take over where we left off, well be my guest, and good f’ing luck. When he was good and done giving the punks what for, he stumbled out the door, fell over, and awoke a while later to the sight of one of New York’s finest looming over him.

Time was the cop might have put the boots to him. Not any more. The erstwhile rebel and scourge of polite society, by now a beloved public figure, instead got the star treatment. No drunk tank for Pete, no rough handling. No, it’s all up you get Mr. Townshend, there you go, and look, so long as you can walk, by all means get yourself home to sleep it off. Seems like no matter how hard you try, sooner or later, you wind up as an elder statesman, waving the banner for some sort of Establishment. Hope I die before I get old, remember? That was the worst part. That, and how the two purported louts from the Sex Pistols had only come over to express their undying admiration for Pete’s body of work, and how much his music had paved the way for guys like them. They truly admired him – in fact, observing the sorry state of their drunken hero, they were worried about him. “Steve and Paul became real ‘mates’ of mine in the English sense”, Pete recalled. “We socialized a few times. Got drunk (well, I did) and I have to say to their credit, for a couple of figurehead anarchists, they seemed sincerely concerned about my decaying condition at the time”. That was something, eh? Oy. You had to have landed somewhere close to rock bottom when the bloody Sex Pistols were concerned.

Pete certainly was spiralling downward at this point, but not as badly as Keith Moon, who’s captured on celluloid above for one of the last times, during the filming for the documentary The Kids Are All Right. Just a month after Who Are Youhit the record stores, he swallowed a handful of whatever pills were within arm’s length, as was his habit – ironically, this time, a prescription drug called Heminevrin, used to combat alcoholism – and overdosed. The band carried on, but really, it could never be The Who after that.

Warren Zevon: I Was In the House When the House Burned Down (January 24, 2022)

A fitting soundtrack for our times, as the black, acrid smoke rises over the pyre of our civilization; at this point, what could be more on the money than this rollicking, hard-driving saga of long good parties coming to an end, being in the right place at the wrong time, and knowing when to cut your losses and get the hell out of Dodge?

Known to casual listeners mainly for Werewolves of London – a good enough song, but oh, how he must have grown sick of it – Zevon was one of those talents cursed, like Randy Newman, to appeal mainly to those who had more than their fair share of wits about them, didn’t balk at looking ugly truths in the face, and figured that sometimes it’s just as well to laugh as cry. Listen, it’s not easy conquering the charts as a Thinking Person’s Songwriter – you try getting to the top of the pops when your stock in trade is wry observation, sardonic commentary, and black humour – but he wasn’t a complete stranger to commercial success. His 1978 album Excitable Boy made it into the top 10 on Billboard, and covers by other artists earned him a fair stipend. It helped, of course, that he rocked as hard and as cleverly as he did, while sprinkling heartbreaking ballads amid the rougher numbers, like, say:

…or

Again the parallel with Newman: Zevon wrote what passed for love songs only on condition that he got to play the lousy boyfriend. Self-aware, maybe, perhaps even sympathetic (especially when brought up short by one of those uncomfortable bouts of self-awareness), but lousy all the same. Anyway, romance, broken or not, wasn’t half as fun or interesting as, say, geopolitics, religion, crime, skullduggery, or clinical depression – the human condition embraced so many themes worth writing about, all of them, apparently, quite shitty, yet often hilarious as well. Why compose something along the lines of “I love you / yes I do / and I hope / you love me too” when instead you could start a song like this:

Hell is only half full

Room for you and me

Looking for a new fool

Who’s it gonna be?

It’s the Dance of Shiva

It’s the Debutantes ball

And everyone will be there

Who’s anyone at all

…or this:

Gonna lay my head on the railroad tracks

I’m waiting on the double E

The railroad don’t run no more

Poor poor pitiful me

…or this:

I went home with the waitress, the way I always do

How was I to know, she was with the Russians, too?

I was gambling in Havana, I took a little risk

Send lawyers, guns and money, dad, get me out of this

It might not have lit up the charts, but it was the sort of catalogue that earned you a hard-core following, especially among his peers, who clamoured to record his songs and contribute to his albums as session players and back-up vocalists. He had fans in the broader show-biz community too, David Letterman, on whose show Zevon appeared often, most prominent among them. It was fitting, then, that it was during an appearance on Letterman, in 2002, that Zevon disclosed there was one last bitter truth to be faced: he was dying. Somehow, along the way, he’d contracted mesothelioma, an appalling and generally fatal respiratory condition brought on by exposure to asbestos, possibly during his childhood when he used to play in the attic spaces of his father’s carpet store. He told Dave that there was an upside, in that “they certainly don’t discourage you from doing whatever you want, it’s not like bed rest and a lot of water will straighten you out”, and gave the audience a very Zevon-esque prescription for seizing the day: “Enjoy every sandwich”. He was the only guest that night, and played a number of songs, including Mutineer, attached above, and Roland the Headless Thompson Gunner, a typically, er, eccentric number about a Norwegian national who becomes a mercenary, and finds himself in the thick of what became known as the Congo Crisis, a nasty African conflict of the 1960s in which the protagonist gets his head blown clean off, but remains in the fray as a vengeful ghost. Letterman’s request.

Afterwards, Dave spent some time with him backstage. This is him quoted in Rolling Stone:

After the show, it was heartbreaking — he was in his dressing room. We were talking and this and that. Here’s a guy who had months to live and we’re making small talk. And as we’re talking, he’s taking his guitar strap and hooking it, wrapping it around, then he puts the guitar into the case and he flips the snaps on the case and says, ‘Here, I want you to have this, take good care of it.’ And I just started sobbing. He was giving me the guitar that he always used on the show.

Likely nobody abhorred clichés more than Zevon, yet, as a close listen to his music made obvious, he embodied one of the oldest, the gentle soul and wounded heart behind the brittle and cynical facade.

He lived just long enough to see the release of his final album, The Wind, which included contributions from Ry Cooder, Bruce Springsteen, Don Henley, Jackson Browne, Jim Keltner, T-Bone Burnett, and others. It’s final song was Keep Me in Your Heart, in which he wrote his own epitaph:

No more laughing at fate, just sad acceptance, and the heart to exit with grace and dignity.

Jackson Browne – The Only Child (April 4, 2022)

A father, perhaps thinking of a time when he won’t be around anymore, speaks plainly to his son, and imparts a few words to live by: remember to be kind, have a care for all those around you whose lives are blighted by heartache and loneliness, and look after your loved ones, especially your mother and brother.

I reckon it can’t hurt, about now, to be reminded that there’s still such a thing as empathy.

Bobbie Gentry – Ode to Billy Joe (August 9, 2023)

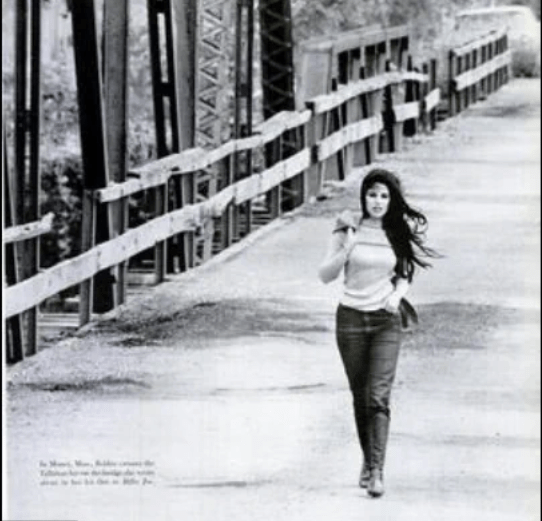

The first time I heard Ode to Billie Joe was on a 1967 Radio 1 special. Amid ornate psychedelic pop sounding a little like Strawberry Fields Forever, this tale of suicide, loneliness and familial breakdown was unlike any record I had ever heard. The place names – Tallahatchee, Carroll County, Choctaw Ridge – were cinematic, the singer’s voice was husky, the string arrangement was minimal and eerie. What I heard was thick mud, damp moss, a barely moving river, dead air. The song was an inescapable fug. You couldn’t move. You had to listen.

Bob Stanley, writing in The Guardian, Oct 17, 2018

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2018/oct/17/bobbie-gentry-trailblazing-queen-of-country

Normally, I’m the only guy allowed to wax eloquent around here, but I came across the article linked above, and I couldn’t imagine writing anything more deftly evocative of the mood conjured by today’s selection than Bob Stanley’s almost poetic opening paragraph.

Hard to believe, but Ode to Billy Joe was Bobbie Gentry’s debut, arriving like something out of time from somebody out of nowhere. All of 23, she wrote and produced it herself, which was practically unheard of for a woman back then, without any expectation that it was going to amount to anything. In fact, it was meant to be the B-side of her first single, occupying the space where songs usually go to die, and arranger Jimmie Haskell recalls that he was given complete freedom to ignore the commercial conventions and just indulge himself when scoring the string accompaniment, “because nobody was ever going to hear it anyway”. He decided to do something different, explaining that “Bobbie’s lyrics are like a movie, so I composed the string arrangement as if it were a movie,” to which end he wrote the score for four violins and two cellos, not the typical pop music string section, and close-miked the cellos for effect.

Once they’d heard the final form of the recording, as adorned with Haskell’s strings, the higher-ups at Capitol records, to their credit, realized they’d be nuts to release it as a B-Side. The song was captivating, haunting, and refreshingly different in so many ways, not just as compared to the popular hits that had thus far defined the sound of the 1960s, but especially when juxtaposed to the stuff that was dominating the airwaves as 1967’s Summer of Love drew towards its trippy zenith. The reigning Billboard number 1 when Ode to Billy Joe found it’s way to the AM radio DJs was All You Need is Love, accompanied on the charts by all kinds of flower-powered psychedelia, songs like Whiter Shade of Pale, Light My Fire, Somebody to Love, San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair), Incense and Peppermints, and White Rabbit. The Zeitgeist album of the era was Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, released just a couple of months earlier. Now along came this almost languid, downbeat, deeply personal, utterly compelling outlier that sounded as if it might have been written by some poor sharecropper’s daughter sometime before the turn of the century (albeit an awfully talented sharecropper’s daughter). It was hard to pigeonhole, too, not exactly country, not really folk, certainly not rock (I’ve heard it described as “Southern Gothic”), and not about anything you’d expect in a hit single. Everybody else was singing about peace, love, and a dawning age of utopian co-existence, while Gentry, both feet planted firmly on the ground, was telling the sad story of a young man’s suicide down in dirt poor Mississippi, with dry, matter-of-fact authenticity, as if deliberately to draw the blinds on all that cosmic sunshine.

It begins almost like a novel, setting the scene in spare, uncomplicated language, forming a narrative that sounds so true to a certain way of life that you wonder whether maybe this isn’t just somebody’s made-up story:

It was the third of June, another sleepy, dusty Delta day

I was out choppin’ cotton, and my brother was balin’ hay

And at dinner time we stopped and walked back to the house to eat

And mama hollered out the back door, y’all, remember to wipe your feet

And then she said, I got some news this mornin’ from Choctaw Ridge

Today, Billy Joe MacAllister jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge

Kinda grabs you right away, don’t she? There you are, absorbed in the mundane details of an unremarkable day, when – wait – what? Did Mama just say, in an off-hand sort of way, that somebody they know had just thrown himself off a bridge? Why, for God’s sake? Listening for an answer amid the banal dinner table conversation, we’re drawn into a mystery, learning along the way that the narrator was Billie Joe’s girlfriend (though nobody present seems to realize it), but then, frustratingly, precious little else. There’s just that one tantalizing clue, and boy oh boy, do we ever want to know what it was that Billy Joe chucked off of that bridge before he killed himself. A lot of people thought it might have been an engagement ring, tossed because the narrator had rejected his proposal, in which case the poor kid died in a fit of romantic despair. Others felt it must have been the evidence of something more terrible, something unforgivably transgressive, even criminal, and so unspeakable that the kid couldn’t live with the guilt. All we could do was speculate, because Gentry never tells us. That’s the real genius of it. This isn’t The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia, with a big reveal at the end. The mystery lingers, and it drives us to distraction.

Over the years, before she withdrew from public life, she must have fielded the question a million times: for the love of God, woman, what did he throw off the bridge? A murder weapon? A secret journal? Yikes, a stillborn baby? Tell us! She wouldn’t, because she honestly couldn’t; Gentry didn’t know, either. She’d never developed any fixed ideas about it, it was supposed to be a mystery, the solution to which, she’d always stress, was wholly beside the point. The song isn’t really about what caused the boy’s suicide, it’s about indifference to tragedy, absence of empathy, and the passive, often unconscious forms that cruelty can take. Nobody at that dinner table cares even a whit that a tortured soul, a person they all knew, just put an end to himself, nobody but the narrator anyway. It’s just something noteworthy, is all, the kid up and jumped, isn’t that a shame, but then that boy never did have a lick o’sense, and pass the biscuits, would you? From the Songfacts article:

When Record Mirror asked Gentry in 1967 what was thrown from the bridge at the end of this song, she replied: “It’s entirely a matter of interpretation as from each individual’s viewpoint. But I’ve hoped to get across the basic indifference, the casualness, of people in moments of tragedy. Something terrible has happened, but it’s ‘pass the black-eyed peas’, or ‘y’all remember to wipe your feet.'”

You get the sense she considered this disheartening numbness to the pain of others as simply the product of immutable human nature. It’s just the way it is, you know, like it always was, it goes like it goes. People live, people die, the world keeps turning, the muddy Tallahatchie keeps flowing down towards the Mississippi River, and that’s pretty much all we can know for sure when the song winds up. The final verse serves as a sort of anti-climax. She tells us a year’s gone by since that day that Billy Joe died. In the interim, her brother got married and moved away, her father was killed by some virus that was going around, and her mother fell into what sounds like clinical depression. She says she still makes regular visits to Choctaw Ridge, where she picks flowers to throw off the bridge in Billy Joe’s memory, suggesting that despite what sounds like the dull affect of her delivery, the suicide (and maybe her own part in whatever led to it) has left her regretful, maybe remorseful, and probably heartbroken. We can’t really tell. We aren’t ever going to find out, either, because she’s done talking. End of story. That’s literally all she wrote. No redemption, no answers, no resolution, and nothing to be done. Look, if you were hoping to tap your happy little toes to a buoyant feel-good joyfest of a tune, you should have gone and listened to something by the Beach Boys, or maybe the Monkees, somebody like that. Bobbie wasn’t here to sugar coat it for you.

Upon its release, Ode to Billy Joe knocked the Beatles down to number 2 on both the album and singles charts, with the 45 holding down the top slot for four weeks. It went on to win multiple Grammys: Best New Artist, Best Vocal Performance, Female, and Best Contemporary Female Solo Vocal Performance, as well as Best Arrangement Accompanying A Vocalist Or Instrumentalist, for Jimmie Haskell’s innovative score. 7 albums and 11 charting singles followed over the next four years, at which point Gentry, as enigmatic as her most famous song, made like Bobby Fisher and quit the recording business while she was on top. She did shows in Vegas up to 1981, and then vanished altogether. She’s barely been seen, and has never been interviewed, since.

So that’s two mysteries she’s left us.

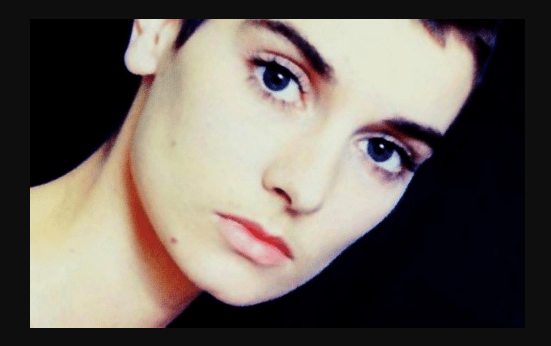

Sinead O’Connor – Mandinka (July 27, 2023)

The obituaries make it sound as if only two things ever happened in her life: first, she had a massive global hit in 1990 with a cover of Prince’s Nothing Compares 2U, and then, two years later, she blew up her career by tearing up a picture of the Pope on SNL, exclaiming “fight the real enemy”. But for that intemperate, ill-considered little tantrum, so the story goes, she could have been huge, a continually multi-platinum rival to Madonna, and it was such a shame, you know. Such a squandering of potential. Was it deliberate self-sabotage? Was she some sort of kook? Didn’t she want to be a star?

Well no, actually, she didn’t. Not a pop star like Madonna, at any rate. A brilliant seeker with a troubled past, if she wanted to be anyone, it was more likely somebody like Woody Guthrie or Bob Dylan. She wanted to be – was, as far as she was concerned – a protest singer. She wanted to fight for justice and make a difference, and what better place to start than by calling out the Catholic Church for its horrific record of child sexual abuse? So it cost her – so what? In later years, when asked if she had any regrets, the answer was always a swift, emphatic, and entirely heartfelt “Hell no!!” The way she saw it, the SNL affair wasn’t a derailment, it was a necessary course correction.

Was this antipathy to conventional pop stardom the reason for the shaved head? Was it a sort of declaration of purpose, an attempt to distract from her extraordinary physical beauty, a signal that she meant to be taken seriously and wouldn’t allow herself to be objectified? Yes, probably, all of that, but only as a continuation of a tactic she’d adopted as a child, as a rebellion against her mother’s cruel habit of introducing her and her sister to strangers as “my pretty one and my ugly one”. It enraged her, every time. What sort of mother does such a thing? It wasn’t even true. Her sister wasn’t homely; she had beautiful red flowing hair, and enviable looks, and Sinéad was sick to death of being pushed forward as the “pretty one” to the denigration of her sibling. So she cut off most of her own long hair, leaving, one suspects, a deliberately jagged mess. There. Try calling her the pretty one now.

When somebody was being wronged, you had to stand up and do something, didn’t you?

Anyway, she didn’t want to be pretty, pretty girls catch predatory eyes and suffer endless harassment almost everywhere they go. She’d learned that the hard way.

Nothing Compares 2U remains the one that everybody remembers, and featured a vocal performance for the ages – one of many – but for some reason I never much liked the song, despite my high regard for its composer. I much prefer today’s selection, a scorching, anthemic rocker from her 1987 debut album that should have been every bit as big. Lord above, that voice. The range, and sheer power of it. In an era that enjoyed more than its fair share of remarkable female vocalists, from Whitney Houston and Janet Jackson to Annie Lennox and Delores O’Riordan, O’Connor still managed to stand out. I don’t think there was ever anybody better.

So what’s Mandinka about, anyway? Beats me. Curiously, most of the American rock press seemed to have no idea what a “mandinka” even was, which is strange in a country in which upwards of 130 million viewers had tuned into Roots, the epic TV miniseries based on Alex Haley’s bestseller, in which the author purported to trace his family’s lineage all the way back to a member of the West African Mandinka tribe. Even understanding it that much, though, why this group of Africans? What did that have to do with the life of an Irish girl? Sinéad herself said it was related somehow to the events in Haley’s book, and left it at that, leaving the rest of us to wonder whether she was identifying with the victims of the slave trade (a high percentage of those abducted into slavery were Mandinka), or protesting, as a young woman not so far removed from her own sexual awakening (she was only 20!), the abuse that she, as a female, was sure to endure, much as Mandinka girls are expected upon maturity to submit to ritual genital mutilation. Both maybe? Or what?

Man, I don’t even have an opinion. Doesn’t matter. Whatever it’s about, it rocks like nobody’s business. You could slot it in on a mixed tape between U2’s Gloria and the Velvet Underground’s Rock and Roll, keeping company with the Clash doing Safe European Home and the Stones cranking Street Fighting Man, and buddy, that’s plenty good enough for me.

Look at her in 1987, all of 20, fierce and confident. She burned so very brightly, didn’t she? How can it be she’s gone? She was only 56. Younger than I am.

A touching thread posted on Twitter today by Russel Crowe:

To enjoy another aspect of her vast talent, listen to this rendition of Silent Night, to my ears the most beautiful ever performed:

Radiohead – Fake Plastic Trees (May 30, 2023)

At one point during the movie Clueless, Cher (Alicia Silverstone) is riding in the car with Josh (Paul Rudd), while Fake Plastic Trees plays on the tape deck, much to the young lady’s disgust. Waahhh, wahhh, wahhh, she says. Complaint Rock. She’s not entirely wrong, I suppose. With today’s selection, Radiohead dished out a heaping helping of bummer, a really rather morbid lament that might properly be called a dirge. It certainly sounds a lot more like the Smiths than the Go-Gos, or, say, a lot more like Randy Newman than Justin Bieber, put it that way. You might even say it verges on lugubrious. I wouldn’t, I think it’s simply melancholy, which isn’t the same thing, but all right. Fair enough. Let’s stipulate to that. Let’s also agree that It’s perfectly understandable if, from where you sit, that’s not at all a good thing. Some folks feel popular entertainment isn’t supposed to bring you down, it’s supposed to lift you up, and give you a moment when you can forget your troubles. If you really wanted to feel sad, helpless, downtrodden, and unappreciated, you’d just go back to work, where that stuff is always on tap, right? You get paid to feel like crap. You aren’t about to volunteer in your spare time, OK? I get it. But I’m an oddball. I just love a depressive and borderline hopeless tune when it’s done just right (what better describes Eleanor Rigby?), plus I’m a complainer, and think everybody should be complaining. Complaint Rock rules!

According to Songfacts, composer Thom Yorke was initially inspired to write Fake Plastic Trees upon first walking around London’s Canary Wharf development, the grounds of which supposedly make liberal use of artificial foliage. This makes no sense, because the Canary Wharf landscaping does no such thing, as near as I can tell from looking into it. Quite the opposite. Yorke has also offered, enigmatically, that the song was “the product of a joke that wasn’t really a joke, a very lonely, drunken evening and, well, a breakdown of sorts”. Whatever its roots, what emerged was what might be called a meditation on the futility of artifice, or, more prosaically, a statement that if what’s real proves elusive, or unsatisfactory, good luck finding joy in the synthetic alternatives:

A green plastic watering can

For a fake Chinese rubber plant

In the fake plastic earth

That she bought from a rubber man

In a town full of rubber plans

To get rid of itself

The lyrics go on to portray a plastic surgeon who performed cosmetic work for girls in the Eighties (plastic surgery for plastic people!), but appears to have packed it in because “gravity always wins”. Then there’s the general emptiness of romantic relationships, which disappoint either because we live in a superficial world full of superficial people who may as well be sex dolls, (if read through a poetic lens), or because the narrator really is making do with a plastic sex doll, take your pick:

She looks like the real thing

She tastes like the real thing

My fake plastic love

But I can’t help the feeling

I could blow through the ceiling

If I just turn and run

…all of which, inevitably, wears him out. Everyone in the song, as we’re told over and over, is worn to a frazzle.

If that doesn’t resonate, or if it would, but you’d rather it didn’t, I won’t fault you. We can still be friends. You’ll bear with me, I hope, when I feel the need for this sort of thing. It gives me comfort, maybe because it reminds me I’m not the only one.

By the by, Cher’s dismissiveness in Clueless is meant to be a comment on her, not the song.

Jesus Jones – Right Here, Right Now (May 20, 2023)

A classic slice of infectious Brit Pop from the late Eighties, Right Here, Right Now rises above the pack by being about something immensely meaningful and important, the ecstatic and seemingly spontaneous destruction of the Berlin Wall by the German people. Not by governments, mind you, but by ordinary people, out there with sledge hammers and pick axes, pounding away, as if there’d never been anything preventing it but the now conquered fear to act. Band leader Mike Edwards was moved to write about it while watching the amazing scenes unfold on TV, having at the same time been listening to another, much more pessimistic song about the tragic mess in which the world of the 1980s found itself. From Soundfacts:

Inspiration for this song struck in 1989 when Mike Edwards was listening to the Simple Minds’ version of “Sign O’ The Times,” which they recorded on a 1989 EP titled The Amsterdam. The song, written and originally recorded by Prince, is his perspective on the troubling events of the late ’80s. While Edwards listened to the music, he watched the Berlin Wall coming down on television. “I never thought that I’d see such a thing in my lifetime,” he told The Guardian in 2018, “and I wanted to write a sort of updated but positive ‘Sign O’ The Times’ to reflect what was happening.”

https://www.songfacts.com/facts/jesus-jones/right-here-right-now

He never thought he’d see such a thing in his lifetime, and neither had any of us. Maybe you remember that giddy feeling, as the Eighties ended and the Nineties began, that extraordinary sense that all the tectonic plates were shifting. For me (and lord knows how many others), the destruction of the Berlin Wall was a singular event that went against everything I thought I knew. By that time, I’d spent about six years of my life in undergraduate and post-graduate work studying international relations, superpower competition, arms and arms racing, and the immutable forces that always led to great power conflict, and I would have told you, as a sage scholar of geopolitics, that there was one thing for certain: the Cold War was a permanent fact of life, or of our lives, anyway. There was no foreseeable way out of the deadlock of mutually assured destruction, as we cowered in the shadow of nuclear annihilation, and faced off against each other along a European frontier delineated by what we referred to, not at all inappropriately, as the Iron Curtain, a term coined by Churchill way back in 1946. 1946. That’s how long we’d been living according to a logic that seemed as inevitable as it was ugly.

To those of us in the strategic studies business, it was thought, actually, that we were in arguably a better position than the ones occupied throughout history by geopolitical competitors like Athens and Sparta, Greece and Persia, Rome and Carthage, France and Great Britain, the fascist Axis Powers and the democracies, and every other set of antagonists whose mutual animosity had thus far shaped the whole course of human history. Things were different now. Horrifying technology had, surprisingly, come to the rescue; we’d finally managed to frighten ourselves, as we all realized that the existence of nuclear arsenals made general war unthinkable. This was a good thing, wasn’t it? All those megatons sitting atop all those intercontinental ballistic missiles were the terrifying abominations that preserved the tenuous peace, a peace longer than almost any we could document between great power rivals of the past. Yes, as long as things remained as they were, this toxic status quo, whether by accident, miscalculation, or the impulse of a madman, might one day turn into something that eradicated pretty much all multicellular life from the face of the Earth. That was the truth, and the truth is not always a pretty thing. Yet we had little choice but to maintain this strange international suicide pact of mutual nuclear deterrence. There was no better way. We faced an implacable foe. Our ideologies were absolutely incompatible. We could never occupy the same planet as them without steeling ourselves for a possibly interminable period of deadly opposition, perpetually armed to the teeth, and always ready to go. Or did you prefer to surrender, and to forsake, for yourselves and all the generations to come, every cherished value and sacred belief you’d ever held dear?

That’s how I was taught to think, and as things were, and seemed likely to remain for generations, there was nothing in that teaching that reeked of false premises. Not then, and not now, looking back. People were what they were, and the world was what it had always been. Your only choice was to pick your poison.

Remember how fast all of that changed? Jesus, it made your head spin. The wall coming down, the Iron Curtain breached, the whole Soviet empire, with its ludicrous and viciously imposed Communist ideology, collapsing under its own weight, seemingly all of a sudden, and with little to no warning. It was like a giant dam bursting. It was, in fact, beyond anything we in the West could ever have imagined. Utterly. Yet there it was, happening, and you felt privileged just to be alive at that moment to see it all go down. The whole world was changing, waking up from history, as the song puts it, and it began to look like Western liberal democracy had won the epic struggle so convincingly that all manner of positive next steps were in the offing, including the democratization of Russia and its many former vassal states. After that, who knew? Maybe Russia could become part of the community of European nations then working towards the creation of the EU. Maybe Russia could even join NATO, changing it into something like the Northern Hemisphere Treaty Organization. We were, surely, on the cusp of a new state of human affairs, a way of being that no longer needed to be so miserable, so futile, so wasteful, so predictable. It was, perhaps, in the celebrated phrase of political scientist Francis Fukuyama, the end of history.

That’s the feeling that Right Here, Right Now, written at the peak of that euphoric moment, captures perfectly within the narrow compass of a three minute pop song. The sheer joy and relief of it. The realization that what you were seeing on the news marked the beginning of a new and better time to be alive, a blessed moment when civilization was being handed one of the most golden opportunities in history. It seemed within our grasp to usher in what might be a new Belle Époque, or perhaps, even, a period of stability and prosperity unlike anything seen since the Pax Romana. We were present at the creation. Right there, right then.

So, there this superior little pop tune now sits, not just a fondly remembered old blast from the past, but more like a curious and captivating relic pulled out of a time capsule, documenting a brief interlude in the bloody sweep of human history when it looked as if we might really be turning a corner. In bitter retrospect, well, so much for that. Now that a new war of aggression and conquest rages in Europe, as dark men seek to reconstitute all of the most sinister constructs of a former dark age, it seems impossible to believe that we ever lived, however briefly, in such a beautiful place. But we did. I was there. I saw it with my own eyes, as baffled as I was thrilled at the wonder of it all. I listen to this song today, and I’m taken back to that ephemeral respite when even the most jaded cold warrior, somebody like me, could really believe that the old dream of peace and good will among nations was no longer a naive and pitiable fantasy.

We were wrong. Of course we were. For once, though, we were wrong for all the right reasons. I remember that hope so vividly. I’ll never forget it, and I doubt I’ll ever feel it again.

Pete Townshend Let My Love Open the Door (May 7, 2023)

Well now, since we are, apparently, in the business of providing daily reminders about how much frickin’ time has passed since we were actually as young as we all still feel, I give you Let My Love Open the Door, a song I reflexively file under “Pete Townshend – Recent”, which in fact comes from 1980’s terrific Empty Glass, his second solo record. 1980. Well, that was recent, when I was in my first year of university, and the Who’s glory days in the mid-Sixties seemed like ancient history, even though I was closer then to 1965 than I am now to the year Rhianna had everybody transfixed with her umbrella-ella-ella-eh-eh.

Attached above are the album cut, a nice live rendition from a 1993 concert at the Brooklyn Academy of music – lovely venue, isn’t it? – and the “e. cola mix”, which reimagines the song as a sort of power ballad, with a much heftier arrangement (and liberal use of some chords lifted from Pete’s own Baba O’Reilly). I first encountered the latter on the soundtrack of the film Gross Pointe Blank (if you’ve never seen it, for the love of all that’s holy, see it), playing in the background during the scenes at the fateful high school reunion. Over the years it’s become the version I most like.

Townshend never thought all that highly of the song himself, sometimes describing it as “a ditty” (albeit a rare Billboard top 10 ditty), to which I’d counter “maybe so, lad, but it’s a hell of a ditty”, and a particularly pleasing change of pace, too, coming from a songwriter who isn’t exactly known for his upbeat paeans to true love. Actually, I’m wracking my brains at the moment trying to think of anything comparable in his catalogue – maybe Now and Then, off Psychoderelict, though that’s a much more nuanced and psychologically complex number with some disquietingly dark undertones – because Pete just didn’t do uncomplicated romance. About the closest he came during the Who’s Mod heyday was The Kids Are All Right, in which the narrator at least seemed to like the girl, even if it would have been better for her if she’d never met him. Apart from that, anybody looking to find straight up love songs on a Who album would instead run into numbers like Pictures of Lily, about, um, making do by oneself with the help of some suitable visual aids, I Can See For Miles, about not being fooled by a lousy cheating girlfriend, and Legal Matter, which characterized settling down into stable marriage as a dive into a hopeless abyss of nine-five office jobs, drudgery, and “maternity clothes and babies’ trousers”, which, sorry baby, wouldn’t do at all: Just wanna keep doin’ all the dirty little things I do / Not work in an office all day just to bring my money home to you. Romance? Romance was for chumps.

So where did it come from, this sunny tune, with its thoroughly conventional sentiments? Was that really Pete, singing lines like this?

I’ve the only key to your heart

That can stop you falling apart

Try today, you’ll find this way

Come on and give me a chance to say

Let my love open the door

It’s all I’m livin’ for

Release yourself from misery

There’s only one thing gonna set you free

That’s my love

That’s my love

Let my love open the door

Say what now? Who are you? Where’s Pete? It’s said that his manager wanted the track excised from the album, arguing, reasonably enough, that “it doesn’t sound at all like Pete Townshend”, but there was no arguing with success, was there? Everybody seemed to like it, publics and critics alike, and what wasn’t to like? Can’t a guy have a little fun for a change? It didn’t always have to be Behind Blue Eyes and Won’t Get Fooled Again, did it? Geesh.

There’s always going to be somebody who’s only mission in life is to gripe, though, and over the years, following the song’s repeated use in TV shows and Hollywood movies, there were critics who’d had enough. I found this in an on-line magazine called Flood, under the title It’s Time to Talk About Hollywood’s Obsession with Pete Townshend’s “Let My Love Open the Door” :

The problem, as I see it, is not that the same song is used in a bunch of movies. Well-known needle drops are part of moviemaking now, for better or worse. But part of the problem is that this particular song, which I do think is very good, isn’t quite good enough to merit such frequent inclusion. It’s not one of our country’s strongest love ballads, I am sorry to say.

In the same article the author refers to the song as “Dad rock”.

https://floodmagazine.com/82466/hollywoods-obsession-with-let-my-love-open-the-door

Dad rock, is it? Not quite good enough, you say? Compared to what? Uh-huh. Black eyes to you, Mr. Grumpy-Pants. I’m sticking with the editors of the venerable industry mag Cash Box, who called it a “joyous, blissful tune [that] features a stirring keyboard-synthesizer melody and multi-tracked high harmonies.” Besides which, the song might have a deeper, more spiritual meaning than is generally understood, as discussed in American Songwriter:

Whatever. I don’t need it to be deep and meaningful, and that’s not on account of me being a big ball of superficial sweetness and light, either, as followers of the Needlefish would certainly affirm if only there were any. Listen here, Bub, nobody likes a sombre, layered, thoughtful piece about something irredeemably awful more than I do. I love Randy Newman, for chrissakes. I love Warren Zevon. I worship A Day in the Life. For that matter, I love Pete, most of whose work takes an awfully bleak and bracingly incisive view of our miserable human condition, when it isn’t examining weighty topics like the roots of faith, and his own quest for a never-achieved, but always longed-for state of spiritual grace. Sometimes, though, you just want something to lift your spirits, and, hell yes and no apologies either, to get your toes a-tappin’. If you can give me that in a sophisticated musical package, I’m sold. From where I sit, Let My Love Open the Door is a wonderful little song.

Critics. Boo. Next thing you know they’ll be telling me I shouldn’t like Wouldn’t It Be Nice, or All My Loving, sour, nasty little trolls that they are.

Fleetwood Mac: Landslide (May 5, 2023)

Included are both the studio recording and a live performance, as well as the superb cover by the Dixie Chicks, just because.

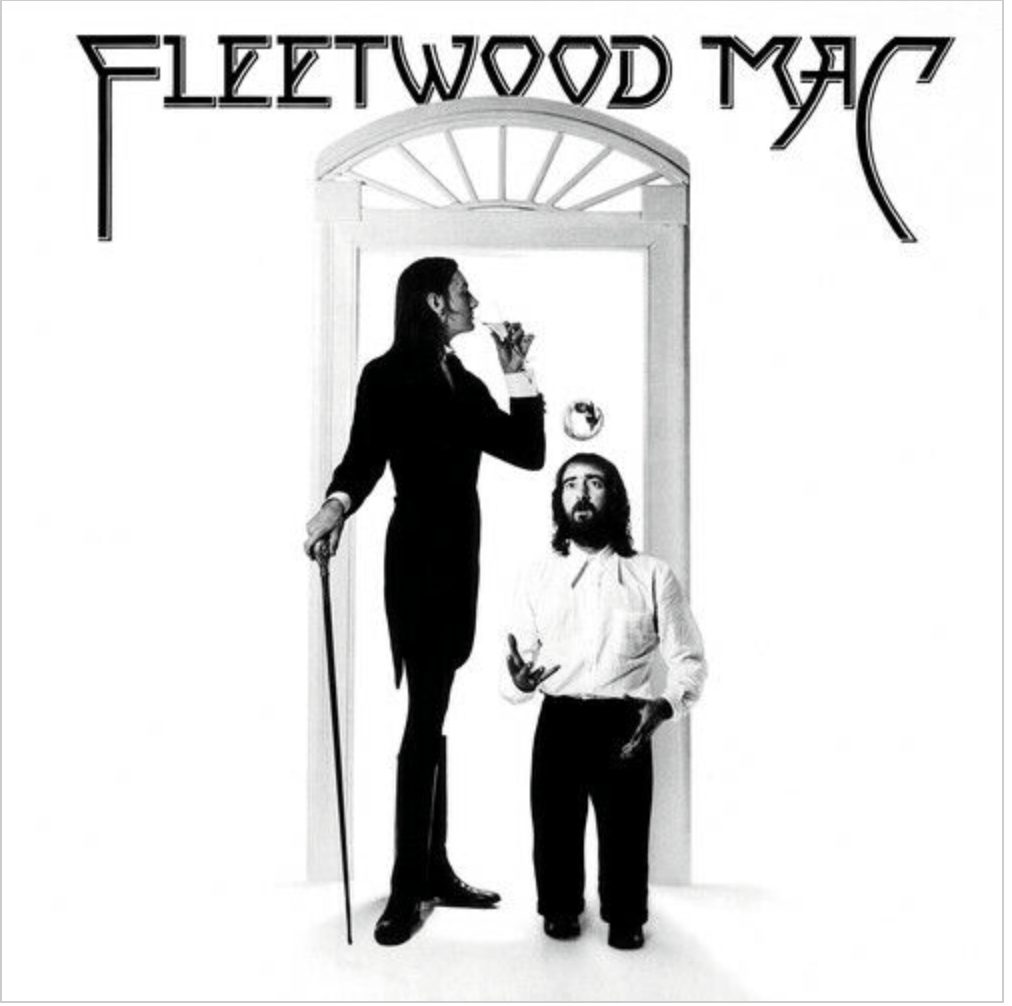

Landslide was one of the standouts on Fleetwood Mac’s first hugely successful album, the eponymous release of 1975, on which newcomers Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham first rounded out the lineup to complete the transition of what started out as an English blues outfit into the radio-friendly pop juggernaut it soon became. I was 14 at the time, and not much into the group. I was far more interested in the music of the prior decade, as I slowly let go of my youthful Neil Diamond fixation and entered my British Invasion phase, while discovering, to my lasting delight, that there was a lot more to the Beatles than the Red and Blue Albums, that the Rolling Stones were actually great, and that there were other acts out there, like the Who, and the Kinks, who might merit some investigation. Through my brother Mark, I learned to appreciate Buffalo Springfield, Creedence Clearwater Revival, and those terrific early albums by Rod Stewart. Fleetwod Mac, and all those other West Coast Eagles-type outfits? Meh. Mind you, our household, like just about everybody’s, had a copy of the record, I suppose purchased by my brother – it was practically compulsory, the thing was everywhere, selling over seven million copies. You remember it:

Just as an aside, this seems, in retrospect, rather an odd choice for what amounted to an inaugural album cover, featuring only drummer Mick Fleetwood and bass guitarist John McVie, both looking a little odd and scruffy. Maybe there’s a story there. Maybe Nicks seemed a bit too glamorous, a little too apt to hog all the attention, though I don’t know how they persuaded the marketing people that they didn’t want this woman’s face on the sleeve:

Were they thinking that nobody whose name wasn’t Ronstadt could look that good and still be taken seriously? One tends to doubt it. Nicks, from the get go, was always a whole lot more than just another pretty face, as Landslide, a painfully soulful meditation on life’s worries and challenges, soon made abundantly clear to anyone who might have doubted it. For many, it was the highlight of the album. It might even be their signature song, though that’s hard to say, since, as the reader will no doubt recall, Fleetwood Mac had a lot of really big songs, perennial favourites like Rhiannon, Over My Head, Don’t Stop, Everywhere, and Go Your Own Way, just to rattle off a few. Yet over the years, Landslide has prevailed as probably the group’s most lasting and beloved track, and certainly, I’d say, their most moving. It really is something, lovely but troubled, weary, introspective, and philosophical, written straight from the heart at a moment when its composer was taking stock of her life, and thinking it might be time to make a radical course change before it was too damned late.

Hard to think of anything more relatable than that.

Joining Fleetwood Mac, and enjoying any sort of commercial success, were still remote prospects when Landslide was written. It was 1973, and she and boyfriend Buckingham were at a particularly low ebb. They’d just released their recording debut, titled, somewhat prosaically, Buckingham Nicks, which landed with such an awful thud that their record label immediately dropped them. It was shattering. They’d had an intoxicating taste of it, what it was like to rub shoulders with the pros in a big record company studio environment, and now they were cast out, having blown what might have been their only shot. The hell of it was, they thought they’d made a really good album. Nobody liked it. What now?

The two were treading water, and not on the best of terms, when Lindsey went out on tour with Don Everly, while Stevie decided to take up an offer to go stay in brother Phil’s place in Aspen, where she found herself sitting in a living room with a glorious, floor-to-ceiling view of the snow-covered Rocky Mountains. She stayed there for about three months, rolling things over in her mind, and taking in all that scenery, especially all that snow, literally millions of tons of the stuff, she’d never seen anything like it, so beautiful, but so terribly dangerous; she couldn’t help but fret about how little it would take, just one wrong move, one loud bang, to bring the whole mass sliding down the slope, killing anybody unlucky enough to be in its way:

I realized then that everything could tumble, and when you’re in Colorado, and you’re surrounded by these incredible mountains, you think avalanche. It meant the whole world could tumble around us and the landslide would bring you down. And a landslide in the snow is like, deadly. And when you’re in that kind of a snow-covered, surrounding place, you don’t just go out and yell, because the whole mountain could come down on you.

The whole mountain could come down on you. Maybe, in a way, it already had. It sure felt that way. Maybe, then, it was time to give up on music. Maybe it was likewise time to give up on romance and other such empty dreams, and just go back to school, where she might learn how to do something better than wait tables and clean other people’s houses, the only other skills she possessed at that point to keep her head above water. Or perhaps she’d never make anything of herself at all, that seemed possible too, she was still only in her mid-twenties, sure, but time was passing, and she was getting nowhere.

Angst, for an artist, isn’t all bad. It can serve as powerful inspiration, just as much as joy, infatuation, or wonder. It certainly was for Stevie. One day, still in the doldrums, the song poured out of her, just like that, lyrics and all, in a span, she later reckoned, of only about five minutes. It was the words that came easiest, really. She just had to put her thoughts and feelings into writing, almost verbatim, while she was still in the moment.

I took my love, I took it down

I climbed a mountain and I turned around

And I saw my reflection in the snow-covered hills

‘Til the landslide brought me down

Oh, mirror in the sky

What is love?

Can the child within my heart rise above?

Can I sail through the changin’ ocean tides?

Can I handle the seasons of my life?

She decided she could, that she and Buckingham had to keep on going, and in later years said that writing Landslide was actually the emotional turning point. This is what she told the interviewer at Performing Songwriter magazine in 2003:

So during that two months I made a decision to continue. “Landslide” was the decision. [Sings] “When you see my reflection in the snow-covered hills”—it’s the only time in my life that I’ve lived in the snow. But looking up at those Rocky Mountains and going, “Okay, we can do it. I’m sure we can do it.” In one of my journal entries, it says, “I took Lindsey and said, We’re going to the top!” And that’s what we did. Within a year, Mick Fleetwood called us, and we were in Fleetwood Mac making $800 a week apiece (laughs). Washing $100 bills through the laundry. It was hysterical. It was like we were rich overnight.

There, now. Who says there aren’t any happy endings in real life?