Jackson Browne: These Days (August 22, 2023)

Don’t confront me with my failures

I have not forgotten them

Sometimes I think those are the most sorrowful, cutting, keenly self-aware lyrics ever written.

These Days, off of Browne’s 1973 album For Everyman, his second, cemented the young singer-songwriter’s reputation as one of the most talented and serious-minded composers then emerging from the West Coast scene. Yet by then it wasn’t new; Browne wrote it, incredibly, back in 1964, when he was only 16, and by the time his own version was released it had already been recorded by a number of other artists, most notably Nico, of Velvet Underground fame, whose take appeared on her album Chelsea Girl in 1967. Browne’s arrangement was largely copied from Gregg Allman’s 1973 rendition, as credited in For Everyman‘s liner notes (many critics, your faithful scribe not among them, think Allman’s version is superior). Since then, it’s been covered again and again, as artists of all stripe have been drawn to the song’s touching humanity and pure, emotional honesty.

It’s beyond me where a teenaged kid found it in himself to write such a sad, philosophical meditation on lost opportunities, mistakes, guilt, and chastened acknowledgment of personal failure, particularly one the central theme of which is broken romance. Could he possibly have experienced any of the things he was writing about? What regrettable, irrevocable decisions had he already made? Who’d he already let down? And what does a 16-year-old know about true heartache and regret, the kind that comes from realizing your own fault in the mess you’ve made? Why, for that matter, is any kid still in high school already on the ragged edge of end-stage moral burn-out? What, he tried out for the wrong sport and didn’t make the team? Pops wouldn’t lend him the car keys? Some girl turned down his invite to the prom or something? Where was all this coming from?

Now, if I seem to be afraid

To live the life that I have made in song

Well, it’s just that I’ve been losin’ for so long

Really, son? You’re already a long-time loser, though still several years too young to belly up to a bar and sob into your whiskey? How’s that even possible? Yet These Days sounds utterly genuine, and could easily pass for the self-written epitaph of somebody reaching the end of his days, lamenting, now that it’s too late, what might have been, having finally gained the perspective that eluded him when he was still young enough to have made better choices. You’d expect something along those lines from a latter-day Leonard Cohen, maybe, or an aging Bob Dylan, not an adolescent still looking forward to the day he’s old enough to vote.

In a recent interview with Sam Jones, Browne relates some of the story behind writing what apparently came naturally, despite his youth:

What can you write about when you’re 16? You know, there are deep questions that arrive in a person’s life way before that, whether or not you’re loved, whether or not you’re accepted by your friends, whether you’re good at anything, or can do anything, and whether you’ve made any mistakes.

Perhaps. There can’t be many, though, who could feel so deeply at such a young age, or give voice to adolescent angst with such heart-felt, convincing maturity.

Of all the commentary I’ve encountered, I particularly like a reaction that appeared in the comments section of a YouTube post, of all places:

Yup.

Nico’s cover (to which she brings the same accented, warbling charm characteristic of her performances in Velvet Underground classics like I’ll be Your Mirror) is attached above, as is Gregg Allman’s, and the pitch-perfect version by Fountains of Wayne, which is my favourite.

Fountains of Wayne (Hollies): Bus Stop (August 30, 2023)

Those of a certain vintage will remember Bus Stop, the sparkling example of mid-1960s pop melodicism, but what’s with crediting this other oddly-named combo? Bus Stop was by the Hollies! It was released in 1966! The attached video is the version the Hollies recorded! Hunh?

Well, no, the attached version is not the Hollies, it just sounds exactly like them in every way, courtesy of my beloved Fountains of Wayne, who displayed their extraordinary skills and pop instincts by reproducing the old hit note for note, instrument for instrument, such that you can barely tell it’s not the original. Why would they do that? For the goggle box, of course! Duh. About 20 years ago, from 2002 – 2005, there was a show on NBC called American Dreams, set in the Sixties, in which one of the characters played a dancer on staff at American Bandstand, the famous Dick Clark top-of-the-pops program – a clever gimmick to showcase the contemporary music. Hits of the day were played by modern musicians imitating the original artists, including Kelly Clarkson, Alicia Keys, Chris Isaak, Liz Phair, the group Third Eye Blind, all sorts of luminaries.* Who better to channel the Hollies than Fountains of Wayne? Who else could more fully understand, or recreate so precisely, such a clever, carefully constructed pop gem?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Dreams

Contrary to expectation, Bus Stop wasn’t written by Graham Nash, but by then up-and-coming songwriter Graham Gouldman, only 19 at the time, who also wrote For Your Love, the first mainstream pop hit for the proto-heavy metal Yardbirds, before going on later to be a founding member of 10cc, a group that enjoyed some success in the Seventies. He came up with the backbone middle eight while he was actually riding a crosstown bus in Manchester, and his Dad supplied the catchy, stage-setting opening lyric, Bus stop, wet day, she’s there, I say, “please share my umbrella”.Gouldman has said it was one of the rare times that a piece of music came to him all in a flash, as pure inspiration. From SongFacts:

Occasionally you can wait for some magic, like McCartney waking up with Yesterday already written in his mind, which does happen – it’s like a gift from your own subconscious. Or sometimes, it’s like a tap’s turned on. When I’d written most of ‘Bus Stop,’ I was actually on a bus thinking about how the middle eight should go. And this whole, ‘Every morning I would see her waiting at the stop / Sometimes she’d shop…’ that all came to me in one gush, and I couldn’t wait to get home to try it. When that sort of thing happens, it’s really amazing. But that’s rare. Mostly, you have to do the slog.

A song penned by an obscure teenager might never have seen the light of day, except Gouldman lived just a couple of doors down from an old friend (and by some accounts manager) of Graham Nash, one Michael Cohen, who was also married to the sister of Peter Noone, frontman to Herman’s Hermits. It was actually the Hermits who recorded it first, but the Hollies got wind of it too, by way of the sort of legendary show biz happenstance that sounds too good to be factual:

Graham Nash got a call from his old friend and manager Michael Cohen…He was asking for help with a peculiar predicament. “This neighbour of mine says her son writes songs, and she’s driving me f@@king crazy,” he said. “Every time I meet her, she asks if I can make you come over and listen to his stuff. Look, I know he’s probably awful and it’s an imposition, but I like this woman. We’ve been neighbours a long time. So would you do me a favour? Just go down there and see what this kid’s about.”

The story goes that Nash actually visited the kid’s house along with a couple of band-mates, and had him audition the song right there in the living room, after which he didn’t need to be asked twice. Yes, they’d record it. Absolutely they’d record it. They knew a winner when it was handed to them on a platter, and they took to it so readily that reportedly, the recording session lasted only a little more than an hour. The rest is history.

I’ve no idea if any of this is true, but as newspaper man and screenwriter David Simon has said, it’s too good to fact-check.

Bus Stop is certainly a stellar tune deserving of its chart success on both sides of the Atlantic – I’ve heard it described as a “perfect” example of pop craftsmanship – but despite its composer’s bout of inspiration on a Manchester bus, I feel constrained to note that two years earlier, Paul McCartney wrote the extremely similar and not at all obscure Things We Said Today, which appeared on the Hard Day’s Night album in Britain (God knows where it showed up among Capitol’s U.S. “butcher” releases – who cares?). You can pretty much sing the Beatles song while playing Bus Stop on the stereo, and the two mesh almost perfectly, at least in the verses. I attach Things We Said Today above, for your convenience.

As we usually say in such circumstances, hey, there are worse things to imitate.

Here’s the version recorded by Herman’s Hermits, whose rendition was considerably less energetic, and to most ears inferior:

*Makes me sorry I never watched it!

The Clash: White Man in Hammersmith Palais (October 17, 2023)

The Only Band That Matters. That was their billing, and you know what, for a while there they really were. Emerging out of the mid-1970s Punk scene in what was then a very dilapidated, run-down, and not at all merrie olde England, the Clash was initially perceived as a second coming of the Sex Pistols, and they were certainly as loud, energetic, and pissed off as Johnny Rotten and friends pretended to be. This was, however, a complete misperception, still shared today by too many in the music press.

They may have looked the part, in their leather and torn clothing, but the Clash was not a Punk band. Its members, led by the great Joe Strummer, were not punks. For one thing, they were hugely talented musicians, and excellent songwriters. For another, they weren’t nihilists, raging against everything and nothing in particular while screaming “no future”. The Clash cared. They were passionate about social injustice. They were, in fact, latter day protest singers in the finest tradition of Woodie Guthrie, hoping to make a difference. There was a future, and they’d have been damned before they let it unfold without doing anything to make it any better than the miserable present. Punks? You wish. The defenders of the status quo could laugh off the performative antics of the punk crowd; the Clash was another thing entirely, and downright scary. These guys were deadly serious, and had serious things to say.

They also rocked hard enough to make the Pistols look like weak-kneed little posers, and Led Zeppelin sound like a lounge act. If you ever require a shot of adrenaline powerful enough to restart somebody’s heart, or for some reason need to blow all the windows out of your house, just turn it up and play Safe European Home, or Guns on the Roof, but here’s the thing: those songs, as always, actually mean something. All you had to do was listen to the words.

Well, all you had to do was listen to the words if you could possibly make them out. Between the accents, the sometimes unfamiliar slang, the intonation, and the general sonic onslaught, the Clash was often notoriously difficult to comprehend. One edition of the Rolling Stone Record Guide quipped that “they’re rumoured to have terrific lyrics, but you’ll never know”, which wasn’t far off, especially for North American listeners. It was certainly true for me, particularly when it came to today’s selection, which I adored from the very first listen and played hundreds upon hundreds of times over many subsequent years without gathering more than a general sense of what it was saying.

One day, the internet age having dawned, I decided to look it up.

White Man in Hammersmith Palais uses Joe Strummer’s attendance at an all-night reggae music festival, which he found both disappointing and discomfiting – he was pretty much the only white person there, and was made to endure all sorts of taunts and threats on that account – as a way into commenting on the toxicity of contemporary race relations, rank socio-economic inequality, the mock counter-cultural hijinks of rival bands that were really only in it for the cash (hunh – they think it’s funny / turning rebellion into money ), and the nasty right wing politics that promised to push the whole mess to its boiling point. Why not phone up Robin Hood, and ask him for some wealth distribution? he sings, before claiming that if Adolph Hitler flew in tonight, the folks in charge would send a limo to pick him up. It was, all things considered, a total f’ing shit show out there. White and black youth had to work together, and find a better solution, which, for those grasping for easy answers, didn’t involve violence and playing with guns. Down that road lay nothing but the Riot Act and martial law, ultimately, and if the rabble rousers thought they could take on the frigging Army, they needed to think again. Maybe Joe understood why the aggrieved would feel that was too damned bad, but it was what it was.

Not exactly Pretty Vacant, is it?

Structurally, harmonically, rhythmically, White Man in Hammersmith Palais showcased a much higher level of compositional ambition than, say, a rouser like White Riot, and was essentially reggae, just like the stuff played at the concert that night, an art form with political undertones that not a lot of white bands had the nerve to take on at the time. Strummer was nervous about how the fans would respond to it. “We weren’t supposed to do something like that”, he said later, “we were a big fat riff group, like, rock solid beats”. He needn’t have worried. Fans loved it, people who’d never before listened to the Clash began buying their records, and in retrospect Strummer reckoned, rightly I think, that it was the best thing he’d ever done. My own inconsequential opinion is that it’s one of the most important songs of the last 50 years, intense, complex, passionate, full of meaning, played and sung to a level rarely achieved by anybody, and in its way on a par with the best work of the Stones, the Velvet Underground, The Who, and other such giants of the golden musical era that preceded them. I’ve certainly heard nothing since that’s anywhere near so stirring, outside, perhaps, of some of U2’s best stuff. Admittedly, at first blush it’s not for everyone, and might even seem grating and unlistenable to those who don’t like it loud and hard, but I’d urge any reluctant listener to give the song a chance. It’s not just loud, and it’s not merely angry. It’s emotional, as befits a really rather thoughtful and heartfelt commentary on so many emotional topics.

The song begins and ends with the goings-on during and after the all-night concert, at which Strummer was hoping the performers would have something meaningful to say to the “black ears there to listen” – he was expecting the sort of protest and social commentary he was himself so eager to put to music – but instead it was all innocuous entertainment with dance choreography, “Four Tops all night” as he puts it, and thus, to him, a lamentable waste of time and opportunity. Taken aback by the hostility of an audience that was none too pleased to have a skinny, pasty white guy in its midst, he made his nervous way home through what was apparently a pretty tough neighbourhood, feeling menaced, and way too Caucasian – by some accounts he also tried to intervene to help a couple of equally out-of-their-element white girls from getting their purses snatched – while wondering, perhaps, whether his vision of greater racial harmony was nothing but a pipe dream. There sure wasn’t a hell of a lot of brotherly love in evidence that night in Shepherds Bush, and it clearly wasn’t the time to preach peace, love, and understanding. At that point, Strummer was happy just to get home without somebody beating the crap out of him. Thus the final verse:

I’m the white man in the Palais

Just a’lookin’ for fun

Only lookin’ for fun

Oh, please mister

Just leave me alone

See what I mean? These aren’t the sentiments of some rowdy punk. Joe wasn’t any sort of street-fighting man, and he wasn’t looking for trouble. He’d only come out to have a little fun, and now just wanted to be left alone while he made haste to get himself out of harm’s way. With any luck, there’d be plenty of time later on to resume the struggle for truth and justice.

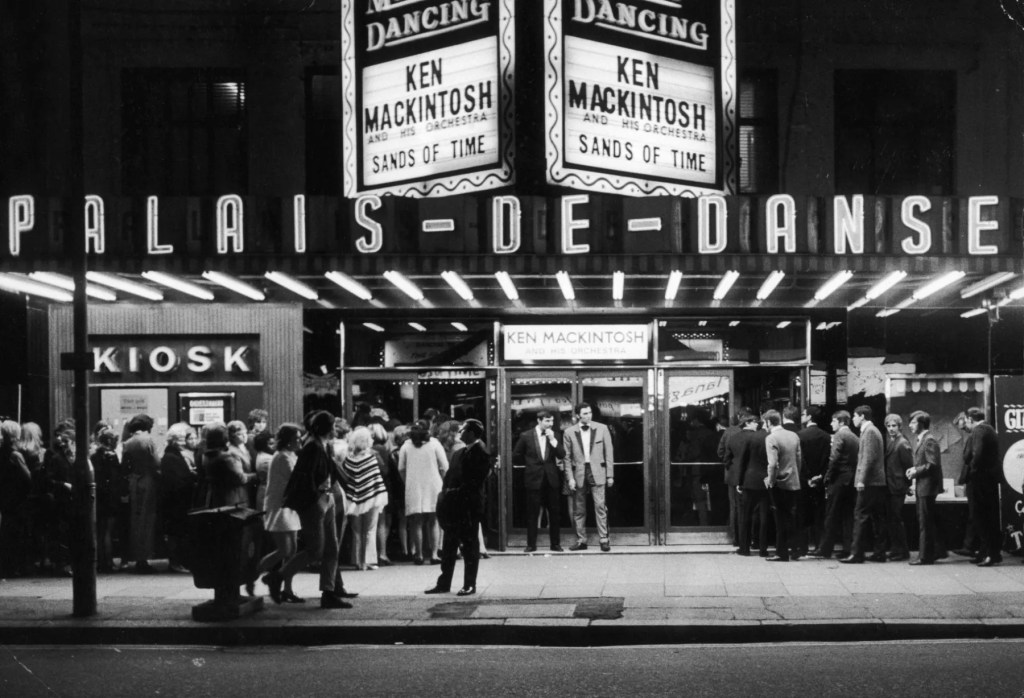

Joe Strummer, sadly, died in 2002, aged only 50, not from drugs, alcohol, or any of the misadventures or self-abuse typically associated with rock stars, but of an undiagnosed congenital heart defect. The song of which he was most proud was played at his funeral. The legendary Hammersmith Palais de Danse, a venue that had hosted everybody who was anybody in its day, the Beatles, the Stones, the Who, David Bowie, the Police, Elvis Costello, you name it, a stream of each era’s most popular artists stretching all the way back to the 1920s, was shuttered in 2007, and finally demolished in 2012.

Matthew Sweet: Feel Fear (October 20, 2023)

…in which Matthew Sweet asks the musical question are you scared out of your wits, or are you just too f’d in the head to understand ? He says it so sweetly, though, with a melody so pure and vertical that you might fail at first to process the lyrics, with Sweet telling you, more in sadness than exasperation, that you’re fooling yourself if you think there’s anything or anybody, down here or up above, that’s ever going to save you. Nope. You’re on your own, friend, and you may as well be on a pogo stick in a minefield. Feel Fear, it’s gentle music serving as a vehicle for sentiments dour enough to come from Randy Newman, is a lot like a velvet pillowcase emptied of its feathers and filled instead with rocks and roofing nails. I love it. It’s simply beautiful, even if you think he’s wrong, which he isn’t.

Buffalo Springfield: Bluebird; Expecting to Fly (November 19, 2023)

It’s high time for Songs of the Day to pay more attention to the wonderful and sadly short-lived Buffalo Springfield, a band so extravagantly talented that the Rolling Stone Record Guide once pronounced them “potentially an American Beatles”. Hard to believe, but we’ve only covered them once before, in an instalment praising On the Way Home, one of Neil Young’s finest compositions. If you haven’t heard it, really, you must:

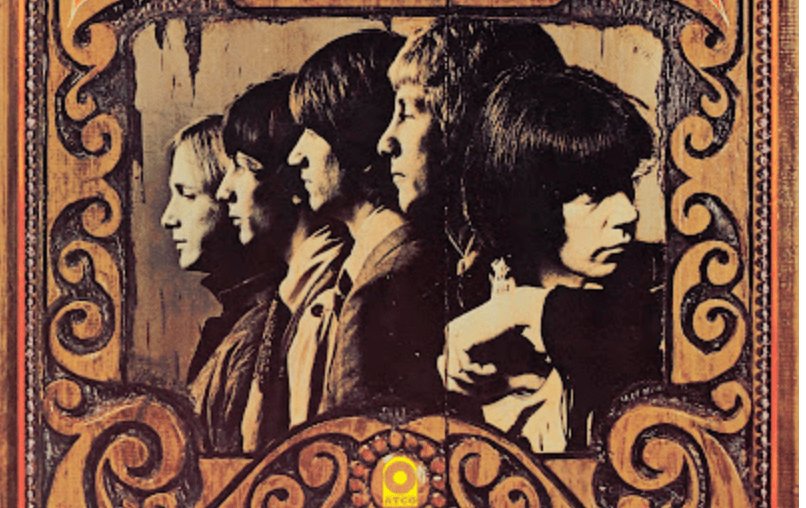

Today’s selections exemplify what made Buffalo Springfield so great and so fascinating, showcasing such levels of songwriting skill, instrumental prowess, and sheer musical ambition that it’s hard to believe that these young men were only at the beginning of their recording careers. Just as impressive is how little the songs have to do with each other. It’s rare for two compositions from the same band, off the same album, to sound so dissimilar; heard separately, they’d probably strike most listeners as coming from different groups, which, in this case, they actually did. You never really knew what you were going to hear from this band. Like the Beatles, Buffalo Springfield was blessed with multiple talented songwriters, each capable of writing in different styles, and like the Beatles, they really had no fixed, definable sound.

Expecting to Fly is an extraordinary early masterpiece composed by Neil Young, a beautiful, melodic, lushly orchestrated, deeply melancholy meditation on loss and failed relationships that showcased an astonishing level of artistic and temperamental maturity for somebody aged only 22 years. The spacious, dreamy production, courtesy of the legendary Jack Nitzsche, was far ahead of its time in 1967, and rivalled the best work then coming out of the Beatles (amazingly, the track was unreleased but already in the can when Sgt. Pepper blew the music world’s collective mind, and Neil worried that it sounded too much like A Day in the Life, especially at the end). Jack also wrote the string arrangement, and, though released as a Buffalo Springfield song, it was actually a solo effort, recorded by Young with Nitzsche and various session musicians.

According to Nietzsche, the song was mainly about “Neil’s fear about getting it on with women”, but it digs a whole lot deeper than that, describing what sounds to be an exceptionally painful breakup and the ensuing heartache. The final verse says it all:

If I never lived without you

Now you know I’d die

If I never said I loved you

Now you know I’d try

Babe, now you know I’d try

Babe, now you know I’d try

…and then, having moved almost imperceptibly into waltz time, the song ends with mournful grace, the strings providing one last flourish, sounding almost like weeping, before everything dissolves into a final resolving note, much as it began.

Hard to believe this is the same guy who wrote Cinnamon Girl, Mr. Soul, and Rockin’ in the Free World. As highly as he’s regarded, Neil is still underrated.

Bluebird was written by Stephen Stills, and it’s probably the best thing he ever produced. Conventional wisdom is that it began life as a tribute to his then-muse, Judy Collins (as, so I’ve read, did Rock and Roll Woman, another Buffalo Springfield gem, and Suite: Judy Blue Eyes, composed when he was with Crosby Stills and Nash). The lyrics portray a woman who’s mesmerizing, inexplicably sad, and essentially unknowable, while musically it’s structurally complex, multi-layered, and played with remarkable assuredness. Stills’s expert work on the acoustic is complimented by Young’s on the electric, the two guitar lines intertwining, weaving in and out of each other with easy fluidity, while Bobby West, standing in for Bruce Palmer, lays down one of the better bass lines of the rock ‘n roll era. Then, perhaps best of all, it’s graced with an unexpectedly sweet and sadly philosophical coda, played by Stills on banjo, that’s simply gorgeous.

Soon she’s going to fly away

Sadness is her own

Give herself a bath of tears

And go home, and go home

The song blends so many elements and styles, with shades of Rock, Folk, Bluegrass, and traditional Country mixing, almost impossibly, with something close to psychedelia. In lesser hands such an attempt at musical fusion would have come out as an incoherent mishmash, yet it all hangs together seamlessly, while at times what AllMusic critic Matthew Greenwald called the “intense guitar tapestry” woven by Stills and Young is almost hypnotic; in concert, their renditions often turned into 15 or 20 minute jams (there’s a nine minute version available on record), the two guitarists improvising extended riffs and playing off each other in a manner that’s been likened to modern Jazz.

Bluebird was highly praised by the critics and made a huge splash at the legendary Monterey Pop Festival, but peaked on the Billboard charts at only 58 when released as a single in 1967. Ritchie Furay later described this disheartening failure as a turning point for the band:

I was sure that we had the follow-up to “For What It’s Worth”… I thought ‘Bluebird’ was the song that was going to make our mark and take us to the top … ‘Bluebird’ was a Top Ten hit in Los Angeles but it couldn’t get out of town. But that was always a problem with the band … Had maybe a hit single appeared, it might have been a different story.

Buffalo Springfield disbanded in 1968. Its members all went on to other things, and generally flourished, especially Young, whose solo work consistently lived up to the standards he’d set for himself so early on. Still, we can’t help but wonder whether the special synergy of their combined efforts had made the group even greater than the sum of its parts, and imagine what wonderful music we would have heard, if only they’d persisted.

Norah Jones: Waiting (January 2, 2023)

A simple song about loneliness, written in the aftermath of Norah’s breakup with former bandmate Lee Alexander, Waiting is one of those songs that’s so beautifully recorded that audiophile nuts like me play it just to hear what all those thousands of bucks worth of stereo gear can do when fed fuel of the proper octane. I chose it today for its particular ambience of pensive, moody, uncertain anxiety, as seems fitting for the beginning of 2024, a year that might one day be regarded as a turning point in the history of western civilization.

So much now turns upon events over which most of us have no influence at all. There are billions of us out here with a stake in this who don’t even get a vote, which feels especially galling when you realize that almost a third of those who dowon’t even bother to go to the polls, just as they never bother. We have to rely upon the rest, most of them utterly insensible to the gravity of the moment, to make the right choice.

All we can do now is wait, sitting here in the calm before the storm.

307 days to go.

Natalie Imbruglia: Torn (January 6, 2023)

The ultimate Pop Tooon? Well, I don’t guess any song can claim that title, but Imbruglia’s version of Torn belongs in the rarified company of those immortal pop confections that come along from time to time, hitting that indefinable but universal sweet spot, bearing up to repeated listenings, year after year, while only the tone-deaf and terminally grumpy fail to get it. When the Beatles were finished laying down Please Please Me in the studio, George Martin leaned over the microphone in the producer’s booth and told them “congratulations, gentlemen, you’ve just recorded your first #1”. Torn is that sort of song. Play it anywhere, anytime, and toes will start a-tappin’, and it’ll be smiles all around. Hard to believe it hit the airwaves way back in 1997; to these ears, anyway, it never gets old. I don’t think it will ever go away, and I don’t think it ever should.

It wasn’t Natalie’s song, much as she made it her own. It was written in 1991 by Scott Cutler, Phil Thornalley, and Anne Preven, members of an obscure group called Ednaswap, whose version had hard edges that Imbruglia later polished smooth. Have a listen – I think it might grow on you:

It’s good, but it’s not quite there, is it? There was also a version released in Danish, by Lis Sørensen, and then another by American-Norwegian singer Trine Rein, but neither of those was about to catch fire in the English speaking world, besides which they were both still missing that certain little something. So it floated around for a few years, largely unnoticed, until suddenly Torn was everywhere, and inescapable. Imbruglia had brought it to life in a way nobody else had managed, not even its composers, and the listening public went wild for it. It topped the Billboard airplay charts for 14 straight weeks.

The theme is pretty straightforward; girl meets boy, girl thinks boy is The One, girl then realizes nope, boy is actually awful. Anne Previn put it this way:

This song is about a woman who thought she found the perfect man, only to find out he was Mr. Wrong all along. To say she is taking it hard is an understatement: she’s so upset that she ends up cold, shamed, lying naked on the floor.

The accompanying video is curious, yet somehow affecting and eminently watchable (Imbruglia was an actor prior to this, playing a role in the Australian soap Neighbours, and the camera loves her), seeming to portray the way that people find it so hard to form meaningful connections, continually harassed, as they are, by outside forces, and hobbled by their own inability to communicate. Or something like that. Incredibly, then 22-year-old Imbruglia selected her own nondescript, loose fitting wardrobe because at the time she felt she was homely. Interviewed in 2022, she confessed that she was “so body dysmorphic and insecure…The army pants weren’t even cool army pants – they weren’t in fashion or anything. My intention in wearing that was so that you couldn’t see my silhouette, because I didn’t want anyone to see”.

Can you imagine? What in the world are we doing to women’s minds?

Torn was by no means the only thing worth hearing on her debut album, Left of the Middle. I’ve always been fond of the self-composed title track:

…but nothing, of course, will ever eclipse Torn in the public consciousness, a song so everlasting in its appeal that 27 years on, Spotify reports 500 million streams, and counting.

Artists often grow weary of the Big Hit Songs that they have to perform at every concert, over and over, as long as they live, but if Natalie feels that way about Torn she gives no sign of it. Here she is with a nice, stripped down version from a couple of years ago:

She also does a lovely version of Neil Finn’s superb Don’t Dream it’s Over. The lady has taste.

cc