Joel Plaskett – The Right Direction (November 22, 2024)

If we run the world with money, can we still walk the streets with love?

A sad, quiet, contemplative number from Plaskett’s sprawling 2020 album 44, fit for those dark nights of the soul that seem to be the only kind we can have any more. It’s a cold, wet November day as I write this, the sun already fading at three in the afternoon, with more rain clouds rolling in, while scattered all around lies the rubble of broken hopes, and dreams perhaps permanently deferred. It’s vanishingly unlikely that anything decent or redemptive will crest the horizon any time soon, but what else is there to do but push, and keep on pushing, ’til we all come around?

It can’t rain forever.

Turnpike Troubadours – Pay No Rent (December 14, 2024)

Live in my heart, and pay no rent.

Old Irish saying

Well, here I am, the guy who keeps insisting he has little use for country music, writing up another ballad fit for a bunch of weary cowpokes gathered around some campfire after a hard day of punching cattle on the open prairie. Have a listen. I think you’ll feel, as I do, that it transcends the superficials of style and familiar musical phrasing.

I heard it just a few days ago on the penultimate episode of Paramount’s Yellowstone. The scene was at a huge outdoor party with a somber theme: it’s the eve of a public auction at which literally every saleable physical asset on the failing ranch, from livestock to old blacksmith’s anvils and everything in between, is going to be liquidated. As darkness falls, the live entertainment, a band announcing itself as the Turnpike Troubadours, takes the stage, and plays a lovely, heartfelt country hurtin’ song. It matched and enhanced the mood perfectly, and the song, so evocative of sadness, loss, and abiding love, was too thoughtful and nuanced to have been thrown together just for the show, much as the group was too good to be fictional.

Written in E Major, the key said to evoke the emotions of restless love, grief, and mournfulness, Pay No Rent may sound at first like a conventional love song, but it was actually composed by lead singer Evan Felker and his friend John Fullbright as a tribute to Felker’s beloved Aunt Lou, owner-operator of the Rocky Road Tavern in Okemah, Oklahoma (by all accounts a local watering hole of some renown), a bit of a wild child, and a virtual big sister/best friend to the singer as he was growing up:

She was about the only person I could go drinking with at 10 a.m. on a Tuesday. We got to be really good friends. We’d hang out a lot, fish together, cook together, drink tequila, and build a big-ass fire at her place out on Buckeye Creek. She loved that song ‘Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.’ She said, ‘If I ever die––I hope I never do, but if I do––you gotta play ‘Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain’ at my funeral.’

I’m not sure whether Lou’s death came before her time, or what got her. Nothing I can find offers anything beyond how she passed about a year before the release of the album A Long Way From Your Heart, in 2017, and that Felker and Fullbright were rehearsing to perform her favourite song at her funeral when Felker learned that somebody else was probably planning to sing it. Seems Lou’s wish to be played off stage to Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain was something she’d expressed to four or five other musicians, and with that base already more than covered, the boys decided to come up with something new. Beginning at noon on the day before the ceremony, and wrapping up at around three in the morning, they wrote Pay No Rent.

I hear the crackle of a campfire

You’re howlin’ at the moon

We all know that you gotta go

But does it have to be so soon?

Bet somebody’ yelling last call

I hope you get some rest

Hope you found everything that you wanted

In the place you love the best

Are you cracking jokes with the common folks?

Are you serving to the well-to-do?

Well I’ve traveled ’round

And I ain’t found nobody quite like you

And is all this living meant to be or a happy accident?

Well in my heart you pay no rent

Well in my heart you pay no rent

It’s a beautiful sentiment, isn’t it, that old Irish saying, an assertion that true love is given freely, asking nothing in return, to which Lou’s loving nephew adds an implied promise never to forget how much he, in turn, was always so grateful to receive free of charge.

Wild Strawberries – Heroine (January 20, 2025)

Heroine is such a neat, pretty, wistful little pop composition that it transcends my own mnemonic association with one of the darkest, unhappiest periods of my life, my time as a corporate lawyer working on mammoth transactions for a Bay Street law firm. It was the late 1990s, and we were on a deal involving industrial facilities in a relatively obscure locale up in northern Alberta, named, confusingly, Fort Saskatchewan, on account of being located not in the adjacent Province, but on the Saskatchewan river – by the by, you know you’re close to straying off the map when you’re in a town called “Fort” something – and it was high summer. We were there over the solstice, and it was far enough north that the sun didn’t go down until after 11 at night, and was back up by about 4 in the morning. It all comes flooding back to me when I hear this song, the unbelievably long hours at the client’s facility, eating every night at a local watering hole called Gus’s (where once a week, on Thursdays, the featured entertainment was a troupe of itinerant strippers), being screamed at and denigrated by one of the client’s angry minions, who was unhappy with the speed with which we were working, the endless churning of documents, the brain fog of sleep deprivation, a particular night among many when we worked through until dawn, when I sat on a curb with my colleague at the motel where we were all staying, watching the sun come up at 4:15 AM. We were there for weeks. In one six day span I billed 121 hours, 121 billables, no padding, and you know, there are only 144 hours in six days. Multiply 6 x 24. One hundred and forty-four, that’s all there are, and I was up and working for all but 23 of them. Throughout, whichever radio station we were able to receive up there was playing Heroine in heavy rotation, and I heard it again and again, loving it every time, just as I still love it, to the point that it’s woven into the memory of all that grief and stress and exertion and exhaustion in a way that softens the recollection. It was horrible, but there was camaraderie, shared purpose, a powerful feeling of being on a team and having each other’s backs, and now, going on 30 years later, I hear Heroine and remember the whole shit show fondly. Swear to God, I was practically ready to kill myself at the time, but now I look back and miss the sense of belonging. I miss the crew. Heroine makes me nostalgic for an interlude of abject misery.

The mind is a strange thing.

It’s an enigmatic song, written in G, which is supposed to evoke feelings of joy, contentment, and grateful satisfaction; as one on-line source puts it, G is “everything rustic, idyllic and lyrical, every calm and satisfied passion, every tender gratitude for true friendship and faithful love,–in a word every gentle and peaceful emotion of the heart is correctly expressed by this key.” Perhaps, generally, and I wouldn’t argue that Heroine is anything but calm, gentle, and tender, but this time there’s a powerful undercurrent of melancholy disappointment that overwhelms anything idyllic. This is an account of broken romance and failed striving, in which the protagonist admits to having tried just about everything to make it work, of having been willing to assume any persona, play any role – fool, drowning person, or heroine – in the effort to be what was wanted. All for nothing. In a moving, poetic turn of phrase, the singer describes how she’s wound up “sitting on the steps of our mistake”, as if their romance was a tangible place, something they tried to build, a home where they both might have lived, now lying in ruins. She said she loved and needed him, but she was wrong. That was a sunny restful Sunday. Now it’s a dreary mid-week Wednesday. Time to move on.

Jann Arden – At Seventeen (January 28, 2025)

People have been constantly on me about weight. In a roundabout way. When Insensitive was huge and had gone crazy everywhere, the American president of the record company at the time was giving me a lift back from a function. He was a 300-lb. man, a total cliché, and he looked at me and said “You’re 30 lbs. away from superstardom in this country.”

Jann Arden, interviewed by Macleans in 2015

You may, like me, be old enough to remember Janis Ian’s original version, a hit way back in 1975. It was in heavy AM rotation at around the same time as Loving You – which, and apologies to any fans who might read this, I’ve always found singularly unlistenable – and somehow, maybe because they were both songs by female vocalists, the cringe I felt for Minnie Ripperton’s magnum opus rubbed off on the wholly dissimilar At Seventeen, which I therefore dismissed and forgot all about until Jann Arden released her sublime and obviously heartfelt cover in 2006.

Jann, no stranger herself to the stress of trying to conform to male standards of feminine beauty (is any woman?), has said that At Seventeen was the first thing she learned to play when she took up the guitar, which probably tells you something about her own experience of the adolescent high school dating scene. Her intuitive feel for the song is evident not just in her typically pristine vocal but also in the arrangement, which features some expert guitar work, and really emphasizes the relaxed, vaguely jazzy, bossa nova swing that lent the original its air of cool detachment, offsetting what could have come across as maudlin and self-pitying. At Seventeen is an adult’s remembrance of the way it was back when its singer was a naive and hopeful teenager, delivered at a remove, more rueful than bitter, more matter-of-fact than out of sorts. Some hard lessons were learned. It was what it was, and so it remains. The truth may be miserable, but she’s done crying about it.

I adore Jann Arden. She has a terrific voice, and she’s whip-smart and funny as hell. She supplied one of my all-time favourite Twitter ripostes when Sarah Huckabee Sanders, Trump’s spiteful and deplorably mendacious press secretary, announced to the world in a farewell post that she wanted to be remembered as honest and forthcoming, or something equally ludicrous. I want to be remembered as tall and thin came Arden’s immediate reply. It seems she inherited the quick wit from her mom, who, upon hearing the story attached at the top, told her daughter “you should have said you didn’t want to gain that much weight”.

The snappy comebacks always elude you in the moment, don’t they? Even when you’re Jann.

Jane Siberry and K.D. Lang – Calling All Angels (March 31, 2025)

Oh, and every day you gaze upon the sunset

With such love and intensity

Why, it’s ah, it’s almost as if you could only crack the code

And you’d finally understand what this all means

Ah, but if you could, do you think you would

Trade it all, all the pain and suffering?

Ah, but then you would’ve missed the beauty of

The light upon this earth and the sweetness of the leaving

Calling all Angels, calling all Angels

Walk me through this one, don’t leave me alone

Calling all Angels, calling all Angels

We’re trying, we’re hoping, but we’re not sure why

It seemed about time for a pained, heartsick plea for divine intervention.

A prayer, a hymn really, truly worthy of the over-used description achingly beautiful, Calling All Angels begins with the sadness of a funeral – a mother sings, and a baby can be heard crying as the pallbearers hoist the heavy load and proceed, one foot after the other, life going on somewhere not so far away as they pace toward the grave – and ends with the bittersweet acknowledgement that you couldn’t hide from the pain and suffering without also giving up on all the beauty, an insight that feels like resigned acceptance born of hard experience, or perhaps wisdom, supposing there’s a difference. It’s hard to keep the faith, nurture the hope, perceive the light that still sometimes penetrates the darkness, and remain mindful of the good that sometimes offsets the evil; it’s hard to hold fast to the belief that it all has to mean something, to fulfill some sort of purpose, even if we can’t understand. We could use a little help down here.

I don’t know, maybe the angels aren’t coming this time, in fact maybe they never have, but I don’t suppose there’s any harm if we keep on calling out to them, not so long as we steel ourselves to carrying on as if we’re on our own. I’ve heard it said that there’s no such thing as false hope. There’s only hope. I never used to agree, but standing here at what feels like the dawn of a new Dark Age, maybe I’ve changed my mind.

The Police – Every Breath You Take (April 25, 2025)

Every Breath You Take was the keystone single release from 1983’s Synchronicity, one of those monster hit records classifiable as a “zeitgeist album”, as I’ve been referring to them. Buoyed by an unusually artful and ominous video filmed in stark monochrome – directed by UK pop duo Godley and Creme, lately of the group 10CC – it became a massive global chart-topper, holding down the number one slot on the Billboard Hot 100 for eight straight weeks, and rising to the top just about everywhere else, including Canada and the UK. In 2019, BMI, the world’s premier music licensing organization, asserted that Every Breath You Take was the most-played song in radio history, a title which it may still hold, (though in this chaotic age of streaming it’s no longer so clear how these things are measured). It’s one of those songs, like Hey Jude, that became so big, and so familiar, that it’s possible now to forget how thrilling it was to hear it for the first time, or appreciate how great a pop music composition it really is.

I sometimes describe songs as feeling so right, so intuitively pleasing, that by the time you’re only about a minute into your first listen they already seem like old friends. Today’s selection is certainly one of those, and a big part of that is the use of the classic pop music chord progression of I-vi-IV-V (that is, a sequence of four chords built on the first, sixth, fourth and fifth leading notes of a given key), the backbone of a number of songs that will undoubtedly be familiar to the reader. This sequence is not unlike the I-V-vi-IV sequence – which might be the most popular set of chords in all of pop – as discussed in a prior Song of the Day posting about U2’s With or Without You:

As I noted then, these chords have a mysterious sort of magic to them:

For some reason surpassing understanding, the human mind seems wired to respond immediately to those chords, as if they mimic some sound in nature, invariably heralding good things, that our auditory circuits have been naturally selected to favour. It’s the backbone of all sorts of songs, from rockers like the Rolling Stones’ Beast of Burden and Green Day’s When I Come Around to sublime ballads like Neil Finn’s Fall at Your Feet, and McCartney’s Let it Be.

Every Breath You Take uses the same chords, just in a different sequence, but the apparently universal pleasing effect is quite similar. Those of a musicological bent explain it this way:

The 1-6-4-5 chord progression (I-vi-IV-V) is one of the most iconic and frequently used chord progressions in Western popular music. Its timeless appeal comes from its ability to evoke a wide range of emotions, from upbeat and joyful to wistful and melancholic. This progression has formed the backbone of many beloved songs in rock, pop, country, and other genres. It offers songwriters a simple but emotionally powerful tool for creating memorable music…This progression’s magic lies in its blend of major and minor chords. The tonic (I) provides a sense of home or stability, the vi (minor) introduces emotional depth, the IV chord builds tension and complexity, and the V chord creates a sense of expectation that resolves back to the tonic.

https://www.bennysutton.com/chords/the-1-6-4-5-chord-progression

I’d add that these chords, whatever their sequence, somehow lend themselves to an apparently infinite set of tempos, harmonies, and overlaid melodies, to the point that the lay listener, i.e. thee and me, would hardly suspect that the same basic progression is at the heart of beloved songs which to us seem to have nothing in common; I doubt many would think there’s any great similarity between, say, the Beatles classic Let it Be and Green Day’s When I Come Around, or Journey’s Don’t Stop Believing and Ah-Ha’s Take on Me. But there is. Once you’re in on the secret, you’ll be hearing the classic chords everywhere, across almost every genre. Here’s the I-V-vi-IV sequence, played on piano:

And here’s the sequence for Every Breath You Take, played on guitar:

I suppose technically, the verses actually proceed I-V-vi-IV-IV, though note how in the outtro they switch to G-eminor-C-G, or, expressed in Roman numerals, I-vi-IV-I. Among the songs using the same sequence as the verses in today’s selection are Ben E. King’s Stand By Me, the Righteous Brothers’ Unchained Melody, the Ronettes’ Be My Baby, Cyndi Lauper’s Time After Time, Bob Marley’s No Woman No Cry, and numerous others. Curiously, by my research, many sources claim that songs generally considered to be using the sequence upon which Let it Be et al. are constructed, I-V-vi-IV, actually aren’t, but are instead built around I-vi-IV-V, just like Every Breath You Take; my own ears don’t agree, but it seems that if the melody fits one chord progression, it’ll often fit the other just as well.

It’s amazing, isn’t it, how there are certain chord combinations that land in just about everybody’s musical sweet spot, and how the best songwriters know how to deploy them to create an intended mood.

In this case, composer and Police front man Sting was pulling a bit of a fast one, since, as he well knew, we normally associate his chosen chord sequence with a romantic, yearning, loving sort of feeling, and it’s perhaps for that reason that many listeners hear Every Breath You Take as a classic love song (apparently, people have even played it as the first dance at their weddings!). Of course it’s anything but. Even the most casual attention to the lyrics reveals the protagonist to be an obsessive and menacing stalker, and obviously a dangerous character, perhaps a former lover unwilling to let go and drifting into something close to psychosis, or maybe just a head case who never met the poor girl, but believes she’s in love with him anyway. In the words of Sting:

I think it’s a nasty little song, really rather evil. It’s about jealousy and surveillance and ownership…I think the ambiguity is intrinsic in the song however you treat it because the words are so sadistic. On one level, it’s a nice love song with the classic relative minor chords, but underneath there’s this distasteful character talking about watching every move. I enjoy that ambiguity. I watched Andy Gibb singing it with some girl on TV a couple of weeks ago, very loving, and totally misinterpreting it. (Laughter) I could still hear the words, which aren’t about love at all. I pissed myself laughing.

Maybe some folks think that lines like this are about deep and loving admiration:

Every breath you take and every move you make

Every bond you break, every step you take, I’ll be watching you

Every single day and every word you say

Every game you play, every night you stay, I’ll be watching you

Every move you make, and every vow you break, I’ll be watching you

Every smile you fake, every claim you stake, I’ll be watching you

Nope! Not exactly One Enchanted Evening, is it? Godley and Creme, staging the video, understood the thing perfectly. The black and white cinematography looks like something out of The Third Man, it’s pure film noir, and Sting’s face is sullen and menacing throughout. A nice touch is the presence in the background of a nebulous, shadowy figure perched above the band on a swing stage, who’s only pretending to wash the windows, staring, surveilling from up above, always there.

Adding to the song’s inherent beauty is the deft, harmonious guitar work of Andy Summers, who realized this was a piece that required a lot more than the mere strumming of chords, and Sting’s own McCartney-esque bass line, the whole augmented by a lovely and remarkably understated string arrangement. It’s all so pretty that it’s easy to understand how people get confused, especially if they miss the ominous subtext conveyed by the typically excellent drumming of Stewart Copland, whose rhythm has a whip-like, unsympathetic sort of quality, powerful, sharp, and not in the least evocative of tender feelings. Also of special note is an unusually effective middle eight, in which Sting, sounding suitably anguished and frustrated, brings the bridge to resolution with a long, pleading pleeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeease, followed by a repeating series of descending piano lines that land us right back at the tonic G. It really is masterful.

Every Breath You Take, its essential ugliness wrapped in a beautiful cloak, might just be the most unsettling song ever to become the biggest hit of the year. It won a passel of gongs, including the Grammys for Song of the Year and Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group, the Rolling Stone Song of the Year, and the Ivor Novello Award for Best Song Musically and Lyrically, awarded by the British Academy of Songwriters, Composers and Authors. Over forty years on, its popularity remains undiminished. It was voted The Nation’s Favourite 1980s Number One in a UK-wide poll conducted in 2015, and to this day racks up incredible numbers on the music and video streaming sites, to the tune of about two million streams a day on Spotify, for a total of over 2.6 billion so far, and over a billion views thus far on YouTube.

I wonder, how many of this legion of listeners still hear this disturbing portrait of a dangerously obsessive mind as a sweetly romantic love ballad?

Leonard Cohen – Suzanne (May 13, 2025)

A fine song and even finer piece of poetry (it began life as a poem, published in 1966 as part of a collection titled Parasites of Heaven), Leonard Cohen’s signature Suzanne remains one of the most well-regarded and widely-appreciated popular compositions never to crack the Top 40. Part autobiography, part religious allegory, it seems to mean something profound to almost everyone, even though its real meaning is, I’ve discovered, a matter of fierce debate. In completing my customary research for this entry, I encountered all sorts of interpretations, various writers peeling away layer upon layer of supposed substance, and honestly, I’ve never in my life had to wade through such a morass of pseudo-intellectual gobbledygook, while emerging none the wiser.

Maybe the self-anointed intelligentsia are making it more difficult than it needs to be. There’s certainly not a lot of allegorical sub-text to the first and final verses, which actually form a straightforward account of his relationship as a young man with one Suzanne Vaillancourt, née Verdal, a bohemian performance artist and blithe free spirit with whom Cohen became close in his years circulating among the various artistes of the Montreal cultural scene. She was, by all accounts, almost irresistibly alluring, and according to Cohen every man she met fell in love with her. Alas, she was married to a fellow artist, a man so attractive in his own right that apparently, every woman who met him fell in love too, and in his best moments, listening to his better angels, Cohen wasn’t about to do anything to insert himself between the two, even if she’d been amenable, which she wasn’t; he once told an interviewer that as a couple, they were inviolate, you just didn’t intrude into the kind of shared glory that they manifested. Not that he didn’t think about it, of course, c’mon, a guy couldn’t help but at least toy with the idea, just in the abstract, but he satisfied himself with an entirely platonic, albeit exquisitely intimate, relationship that never developed into anything untoward. This is from an interview conducted by Kate Saunders of the BBC:

Saunders: The song is about the meeting of spirits. It’s a very intimate lyric, very, very intimate.

Suzanne: This is it.

Saunders: It seems very sad that the spirits moved apart.

Suzanne: Yes, I agree and I believe it’s material forces at hand that do this to many the greatest of lovers (laughs).

Saunders: So would you say in a way, in the spiritual sense, you were great lovers at some level?

Suzanne: Oh yes, yes, I don’t hesitate to speak of this, absolutely. As I say, you can glance at a person and that moment is eternal and it’s the deepest of touches and that’s what we’d shared, Leonard and I, I believe.

It was beautiful as it was, and it was enough. Well, mainly it was enough. As Suzanne remembered later, once when he was visiting Montreal, I saw him briefly in a hotel and it was a very, very wonderful, happy moment because he was on his way to becoming the great success he is. And the moment arose that we could have a moment together intimately, and I declined. Over the years, there don’t seem to have been a lot of women who said no to Cohen. But Suzanne didn’t want to spoil their special bond.

So this is entirely based in reality, an honest account of a precious moment set to poetry in which no poetic licence is taken:

Suzanne takes you down to a place by the river

You can hear the boats go by, you can spend the night forever

And you know that she’s half crazy, and that’s why you want to be there

And she feeds you tea and oranges that come all the way from China

And just when you want to tell her that you have no love to give her

She gets you on her wavelength, and lets the river answer

That you’ve always been her lover

And you want to travel with her

And you want to travel blind

And you think you’ll maybe trust her

For she’s touched your perfect body with her mind

Suzanne really did have a place down by the St. Lawrence River, where the two used to meet and watch the ships go by. She really did serve him mandarin oranges and exotic, orange-flavoured tea from somewhere in the far east. The poem is practically a photograph.

Saunders: When you heard the song as opposed to hearing the poem, did you instantly think, that’s me?

Suzanne: Oh yes, definitely. That was me. That is me still, yes…

Saunders: Could you describe one of the typical evenings that you spent with Leonard Cohen at the time the song was written?

Suzanne: Oh yes. I would always light a candle and serve tea and it would be quiet for several minutes, then we would speak. And I would speak about life and poetry and we’d share ideas.

Saunders: So it really was the tea and oranges that are in the song?

Suzanne: Very definitely, very definitely, and the candle, who I named Anastasia, the flame of the candle was Anastasia to me. Don’t ask me why. It just was a spiritual moment that I had with the lighting of the candle. And I may or may not have spoken to Leonard about, you know I did pray to Christ, to Jesus Christ and to St. Joan at the time, and still do.

Saunders: And that was something you shared, both of you?

Suzanne: Yes, and I guess he retained that.

Thus the subsequent lines about Jesus, so moving and in a sense enigmatic, written, as they were, by a Jewish artist, would appear to have everything to do with the deep spirituality of his relationship with Suzanne, Cohen seeming to equate reverence for the divine with his intense artistic and aesthetic appreciation of his beautiful muse. His description of Jesus as a sailor was derived, perhaps, from one of his most lasting impressions of Montreal, where he used to look out over the water and think about the perils faced by the men who go to sea, those thoughts becoming intertwined with his memory of watching the ships go by at Suzanne’s place on the river. Said Cohen, recalling the genesis of the poem:

And I knew it was a song about Montreal, it seemed to come out of that landscape that I loved very much in Montreal, which was the harbour, and the waterfront, and the sailors’ church there, called Notre Dame de Bon Secour, which stood out over the river. I knew that there was a harbour and I knew there was Our Lady of the Harbour, which was the virgin on the church which stretched out her arms towards the seamen, and you can climb up to the tower and look out over the river and this song came from that vision.

Black-hearted stone-atheist I may be, but I’ve always been especially touched by this mournful depiction of a Saviour coming to realize, as he suffers on the cross, that his charges can’t be saved, not, anyway, until it’s too late to make a difference:

And Jesus was a sailor when He walked upon the water

And He spent a long time watching from a lonely wooden tower

And when He knew for certain only drowning men could see Him

He said all men shall be sailors then until the sea shall free them

But He himself was broken long before the sky would open

Forsaken almost human, He sank beneath your wisdom like a stone

Only drowning men could see him; it’s almost a corollary of the old saying that there aren’t any atheists in foxholes, Cohen contending that on the other hand, there aren’t any believers outside of them, either. In Cohen’s telling, people only turn to God when they’re in extremis. Until then they live like sailors too, like Jesus did, lonely and at peril out to sea, until finally, at the end, they come to appreciate what Cohen already understood, and had ever since he used to commune with lovely, beloved Suzanne, the deep, captivating woman in the Salvation Army hand-me-downs who saw beauty in the mundane, knew how to find the treasures amid the uncollected refuse, and held the mirror in which the poet saw himself through her eyes.

+++++++++

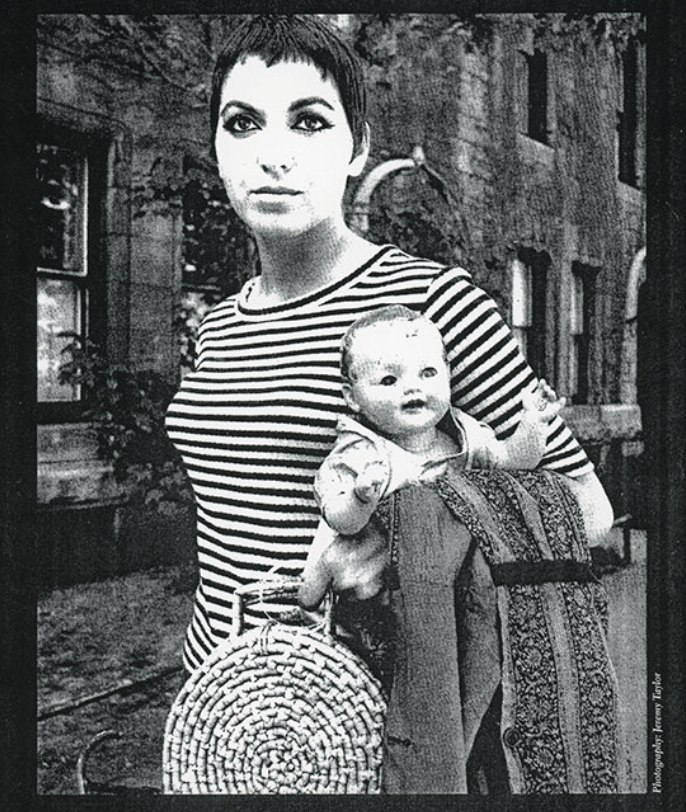

Suzanne Verdal