Kate Rusby: The Wild Goose

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A6tVU–Cbes&app=desktop

A song I just discovered. This is a lovely treatment of an old sailors’ tune, they’re called “sea shanties”, songs that were chanted by crews engaged in hard work, typically hauling on lines — they’d work to the rhythm to coordinate their efforts. They’re actually categorized according to the kind of task performed when sung, and this one is a “halyard shanty”, a halyard being one of the ropes, all of which had disinctive names (we still use “lanyard” these days as common parlance for any sort of rope that gets pulled). Their origins are generally impossible to pin down. Curiously, shanties often refer to a mysterious “Ranzo”, or “Renzo”, as does this one, and this derives from a mythical Ranzo, sometimes Reuben Ranzo, who serves as the protagonist in all sorts of shanties, so Google tells me. It’s thought that “Renzo” may be an abbreviation of “Lorenzo”, as Portuguese sailors from the Azores were common among the crews of whaling vessels, but nobody really knows. Of course the word “shanty”, like the English word “chant”, itself has a connection to the French “chanteur”. The culture of the sea has no nationality.

The Rankin Family: Fare Thee Well Love

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cQF_aB8NDrQ

It sounds like an ancient Celtic lament for loved ones lost at sea, and in a way it is, but it was written around 1990, by Jimmy Rankin of Mabou, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. The Rankins really are a family, and their Wikipedia article says that the girls run a pub in Mabou when they’re not singing. One of the boys, John, died in a car crash about 15 years ago, it was big news out east. Digging around, I was saddened to discover that one of the girls, Raylene, just recently died of cancer. Great. I really should learn to stifle my curiosity.

Gordon Lightfoot: Farewell to Nova Scotia

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vaE9vlrhX-k

In a way it’s sacrilegious for me to pick Lightfoot’s version of this one, he’s a landlubberly Ontario clod-hopper from frigging Orillia, for the love of Christ, but he does a nice job of it. This is pretty much the national anthem back home, recorded by dozens of artists over the years. We were taught to sing it in school, and told the story of how an amateur historian and folklorist named Helen Creighton heard it sung in the parlour of a kindly woman, a stranger, who’d invited her to get in out of the rain. This was back in the early 1930s. Local folk songs like this were passed on as part of oral tradition, and Helen was the first to transcribe it, possibly saving it from being lost to history. Its chorus is now engraved on every Bluenose heart.

Stan Rogers: Barret’s Privateers

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZIwzRkjn86w

God damn it to Hell if this isn’t another maritime classic sung by a land-locked Ontarian, and even worse he wrote the bloody thing. However, he used to spend his summers in Nova Scotia, and his parents were Nova Scotia ex-pats, so I claim him as one of our own, and moreover when he died – in a lousy twist of fate from smoke inhalation in an Air Canada DC-9 that caught fire in mid-flight – his ashes were scattered in the Atlantic off the Nova Scotia coast. Therefore, Ontarian my big white Bluenose backside. The song is full of plausible sounding details of wooden warships and combat at sea, and written in what sounds like the argot of 18th century sea-faring, so many people take it to be an authentic shanty of that era, but nope. Stan wrote it in the 70s, no doubt about it.

A “privateer” was a mercenary, in effect a pirate, but an honourable one; they were civilian sea-farers commissioned by the Crown to harass enemy shipping, under a licence called a “letter of marque”, as mentioned in the song. Halifax was, as the lyrics suggest, a home port for many during the Revolutionary War, when loyal Englishmen fought upstart Americans on the high seas. We fought them again, during the war of 1812, when HMS Shannon triumphantly towed the captured USS Chesapeake into Halifax harbour, after a gunnery duel between the two frigates ended with American defeat. Glorious. Such things spring to mind when you were brought up amidst all that naval history, Stan starts singing and your blood rises as you think about the Royal Navy maintaining Pax Britannica on the world’s sea lanes, and convoys forming up in Bedford Basin, watched over by corvettes and destroyers riding shotgun in the long struggle with Nazi U-Boats, likely to be encountered lurking just offshore. You Upper Canada folk who think those damned lakes out there are impressive bodies of water might be unmoved by Barret’s Privateers. Ah, but what can be done for you, you’re from away.

Song of the Day: The Beatles – A Day in the Life (July 29, 2018)

Another reprint from the archive:

The Beatles (Lennon & McCartney): A Day in the Life

I’m going out on a limb here, but it’s a stout limb, and I feel quite secure. A Day In The Life is the 20th century’s greatest work of popular art. Over fifty years after its recording, it remains sui generis, belonging with no other type of popular music one can imagine – certainly not “Rock” by any sensible definition, much less “Pop”, or “Folk”, though it has elements of each. It doesn’t even seem proper to refer to it as a “song”, the word seeming too diminutive for something so monumental. Parts of it more closely resemble the sound experiments of the 20th century classical avant-garde, but it doesn’t belong in that category either, being intelligible and inherently tonal. To hear it for the first time is to look at a painting composed of colours that no one has ever used before, and can’t even be properly named. There’s so much to think about when listening critically to this amazing…song.

First, though, let’s get something straight. A Day in the Life has passed into popular consciousness as Lennon’s work (which does much to underpin the ludicrous myth that John was the real musical talent in the Beatles). It seems like almost everybody says so, even Paul has said so, but there was one person who always quite emphatically disagreed – John himself. Lennon was always admirably scrupulous in insisting that the piece was a joint effort, with Paul’s contributions being crucial. These are quotes from various interviews John gave over the years to Rolling Stone, Playboy and the like:

“Paul and I were definitely working together, especially on ‘A Day in the Life’ that was a real … The way we wrote a lot of the time: you’d write the good bit, the part that was easy, like ‘I read the news today’ or whatever it was, then when you got stuck or whenever it got hard, instead of carrying on, you just drop it; then we would meet each other, and I would sing half, and he would be inspired to write the next bit and vice versa… So we were doing it in his room with the piano. He said ‘Should we do this?’ ‘Yeah, let’s do that.”

“A Day In The Life – that was something. I dug it. It was a good piece of work between Paul and me. I had the ‘I read the news today’ bit, and it turned Paul on. Now and then we really turn each other on with a bit of song, and he just said ‘yeah’ – bang, bang, like that. It just sort of happened beautifully.”

“Paul’s contribution was the beautiful little lick in the song ‘I’d love to turn you on.’ I had the bulk of the song and the words, but he contributed this little lick floating around in his head that he couldn’t use for anything. I thought it was a damn good piece of work.”

When asked, George Martin was often cagey about whose idea it was, but in some interviews he confirms that the mind-blowing orchestral crescendos that are so crucial to the piece were also McCartney’s; it may be that John had the concept, “a sound like the end of the world”, but Paul was the one who put that idea into music, and you can find a film of Paul conducting the orchestra at the recording session. His inspiration was the work of atonal 20th century composers like Schoenberg, and the radical electronic experiments of Stockhausen, to which he’d been listening closely at the time. As Paul told Playboy in 1984:

The orchestra crescendo was based on some of the ideas I’d been getting from Stockhausen and people like that, which is more abstract. So we told the orchestra members to just start on their lowest note and end on their highest note and go in their own time–which orchestras are frightened to do. That’s not the tradition. But we got ’em to do it.

The entire middle section, of course, was also Paul’s, and I’ve always thought the importance of that part of the piece is under-appreciated. That’s also Paul on piano throughout.

So John arrived with an acoustic number, and Paul gifted him the critical line “I’d love to turn you on”, the middle eight, the piano accompaniment, and the out-of-this-world orchestration that lent it unprecedented gravitas. A Day in the Life would also suffer greatly in the absence of Paul’s typically eloquent bass line. Puts me in mind of an article I found on the BBC Website, by New Yorker contributor Adam Gopnik:

The Beatles’ music endures above all because we sense in it the power of the collaboration of opposites. John had reach. He instinctively understood that what separates an artist from an entertainer is that an artist seeks to astonish, even shock, his audience. Paul had grasp, above all of the materials of music, and knew intuitively that astonishing art that fails to entertain is mere avant-gardism… in those seven years when John’s reach met Paul’s grasp, we all climbed Everest.

You might say that John could point to distant stars that Paul might otherwise have ignored, but only Paul could reach up and grab them.

I wish people would understand this.

That said, let no one doubt that the little acoustic number John brought in to Studio Two was one for the ages, at once spooky, melancholy and compelling. There used to be a video posted on YouTube of George Martin playing take one on the original master tape, and it gave him the same goose bumps decades later as it did in 1967. You can still find an early take:

That sad little “oh boy”, the dull affect, the alienation, this sort of thing could have come from no other songwriter. The lyrics were inspired by a newspaper story about the automotive death of Guinness heir Tara Browne, and John used this as an opening tableau, the “lucky man” who “blew his mind out in a car”. His dry description of the event is, upon reflection, one of the most chilling things ever heard in recorded music. Here is a mind numbed by media saturation, taking note of even the starkest tragedies with interest, but not emotion, seeming half asleep, off in some dreamland, bemused perhaps, but too flat to feel anything, really. He’s just telling you what he saw. It’s hard to express in clumsy words how extraordinary this is, how moving. Well I just had to laugh…I saw the photograph… like a voice from beyond the grave. The voice of someone who sees things clearly, but doesn’t much care any more.

Paul adored it immediately, and as he always did with John’s songs, he composed a bass counterpoint that serves as a superb melodic enhancement, his line ending with the notes E-D-C-D-G, the G in the next lowest octave. You hear this at the end of John singing “I saw the photograph”. Stick a pin in that.

John had a second verse but no middle. Paul offered up a song snippet he’d had bouncing around in his head for some time, but how to transition from John’s part to Paul’s? Initially they had no idea, but knew it would have to be something grand and visionary, so they recorded an empty space, twenty-four bars long, that contained nothing except the voice of their faithful roadie Mal Evans counting out the bars, punctuated with an alarm clock. They repeated this, sans alarm clock, at the end. Imagine, making a blank recording in the certainty that you’ll figure out what needs to go there later. Look, it has to be beyond anything ever heard on a popular record, so give us a minute, we’ll come back to that after we finish this other bit.

When it came time to fill those gaps with Paul’s orchestral orgasms, they held a midnight recording session at Abbey Road, and to get the symphony players into the spirit of things, Paul handed out clown noses, party hats, fake gorilla paws and other paraphernalia for them all to wear. It was vital to take them outside of themselves, disorient them, and persuade their sub-conscious minds that this was different, this was not their day job, and they weren’t to do anything conventional this night. Paul says he gave them instructions that weren’t so much a score as a recipe, just start yourself off at the lowest note, proceed over 24 bars to your highest, and for God’s sake don’t play in unison. Forty-two classically trained musicians somehow managed to do just that, and in post-production they were quadruple-tracked so that what we hear is a 168 piece orchestra emitting what sounds, as ordered, like a great engine spooling up to the full power it needs to destroy the entire world.

Then the alarm clock rings, and Paul’s middle section begins. The insistent banging of a note on the piano sets the tone. While John’s vocal had been enhanced by an other-worldly studio echo, Paul’s is now natural and straightforward. While the rhythm of John’s piece had been lazy and enervated, Paul’s is now hopping along at twice the pace. The fitful night is over. It’s time to get up and get to living another day – another awful, repetitive day.

As originally conceived, Paul’s bit was probably a jaunty sort of “C’mon Get Up, Get Happy!” sort of number, but not any more. Change the arrangement, alter the mood, and sandwich it between sonic cataclysms, and it becomes a horrible wake-up call to a desperate and dreary reality. Gulping down the coffee, realizing you’re already late, then rushing to the bus (listen to John add heavy breathing at this juncture), this is the source of the alienation and apathy we heard in the first verse. If before was a dream, this is a waking nightmare.

Having caught the bus, our narrator falls into a weary waking reverie, and then John’s voice begins a primal wail, and as the orchestra returns and grows inexorably in power, the vocal runs across the stereo image, one speaker to the other, as if trying to flee from the crushing weight of the sound behind it – but it’s no good. With five definitive notes, the blow is dealt, and there they are again: E-D-C-D-G, rendered this time with overwhelming force. This is Paul’s special genius on subtle display. He’s using the same five notes from the concluding phrase of his prior bass line to create a sense of unity, knitting the disparate segments of the song together in a way hardly anyone notices, but most everyone feels at some level.

Back comes John with the final verse, the tempo now matching Paul’s, and we hear of another news story, this one also real, about bureaucrats who somehow thought it was worth their while to calculate how many pot-holes infested the roads in Blackburn, Lancashire. Again, it’s hard to express in words how perfectly this suits the mood of the piece, how the bit about finally knowing how many holes it takes to fill the Albert Hall so fully exemplifies the incessant media noise that has thoroughly desensitized the singer. It’s information devoid of knowledge. It clogs the mind with its uselessness.

Again, now, with the sound of the world ending. Most haunting perhaps is hearing Mal Evans as he’s counting bars, just barely discernible in the mix, “…seventeen…eighteen…nineteen…”, like he’s marking the last few seconds until we must conclude, inevitably, with annihilation. It builds to an unbearable pitch, then ends with utter finality. In the studio, five different players at three separate pianos strike the same E-major chord in unison, and the engineer turns up the gain on the microphones, placed inside the grand pianos right next to the strings, at the same rate as the strings themselves vibrate ever more faintly towards silence, the note seeming to last forever. There’s no electronic trickery going on here. It’s just the sound of the strings fading down to nothing over 42 seconds. At the end the recorders were turned up to the point that you can hear someone in the studio – according to legend, Ringo – shift slightly on a piano stool.

If you’re ever seeking an aural representation of the aftermath of the Big Bang, look no further. Except, the Big Bang was a moment of creation. This is the way the world ends, not just with a bang, or only a whimper either, but both, one after the other.

Song of the Day: The Crystals – Then He Kissed Me (August 21, 2018)

Anyone who’s seen the Scorsese tour de force Goodfellas will remember the scene that showcased one of the greatest tracking shots in cinema history, as Ray Liotta takes new girlfriend Lorraine Bracco through the back entrance into the Copacabana, with Ray jumping the line, getting a special table placed right down in front just for him, and being everybody’s best buddy as he tips the staff with twenty dollar bills (in 1963!) and enjoys all the perqs of being seriously monied and thoroughly mobbed up.

“What do you do?“, she asks him, mystified that anybody not famous like Sinatra could be given such VIP treatment.

The soundtrack is a glorious 1963 pop music confection of the girl group era, the Crystals singing Then He Kissed Me:

There can be no better example of the power of a good tune as amplified by Phil Spector’s legendary “wall of sound” production technique. The Crystals soar over a soundscape of harps, strings, brass, booming kettle drums, maracas, castanets and God knows what else, in another lavish take on the songwriting template that Spector called “little symphonies for the kids”. The arrangements relied not so much on recording tricks as sheer mass of instrumentation; if the song needed a guitar part, why not five guitars, or six, some acoustic and some electric, all playing in perfect harmony? How about forty violins as counterpoint to the melody? Somehow, despite the density of the mix, it was all engineered to sound wonderfully crisp and distinct when played out of the tiny monaural speakers buried in Ford and Chevy dashboards, and mounted in the new portable transistor radios that miraculously made it possible, for the first time, to carry recorded music around with you.

This was before Messrs. Lennon and McCartney changed all the rules, when singers were handed songs written by professionals over in the Brill Building, and producers and professional arrangers decided what the record would sound like. It was mechanical, but it could be magical, too. Those weren’t soulless mercenary hacks working away in the office tower. No sir, it was Goffin and King, Leiber and Stoller, Burt Bacharach, Johnny Mercer, Neil Diamond, Ellen Greenwich and Jeff Barry (co-writers of Then He Kissed Me), among other luminaries. This model of professional songwriters and producers creating a particular genre of music, an official “sound”, wasn’t quite on its last legs yet in 1963; something similar to the Brill Building Sound was generated later over at Motown records in Detroit, where the songwriting team of Holland-Dozier-Holland cranked out an unbelievable quantity of hits that rank among the best pop music ever recorded. Still, the tectonic plates were soon to be shifting in the aftermath of that epochal Sunday night in February 1964, when over 70 million people tuned close to half of all the TVs which then existed in the U.S. to CBS and the Ed Sullivan Show, eager to see what all the fuss was about with these long-haired kids from England.

By the 1970s we were into the era of singer-songwriters, and performers that wrote their own material had become standard. From where I sit, the results have been decidedly mixed. The new normal established by the Beatles, it turned out, produced the best outcomes when the band happened to include two of the greatest songwriters who ever lived. Given that sort of alchemy, songs for the ages might be sold to the masses. Otherwise, well, maybe not so much. Not that there haven’t been those equal to the task, but when you leave the average group of guitar-playing yobbos to their own devices, you might get something good, or you might just as likely get this:

On a visit to New York in the early 2000s, when the tuneless moaning of Nickleback was all over the airwaves, I was taken aback when I realized I’d just walked past this:

It seemed to me then like a monument from a lost golden age.

Song of the Day: The Dixie Chicks – Not Ready to Make Nice (September 15, 2018)

A song of transcendent power that very much bears revisiting now, in the depths of the Trump era, when the horror of the present political reality is apt to nudge us towards an entirely misguided reassessment of the last Republican regime. The Dixie Chicks flourished when George W. Bush and his black-hearted crew of right-wing operatives, Cheney, Rumsfeld, et. al., ruled the roost and worked to carry out the hubristic, disastrous, nationalistic agenda developed in think tanks like the Project for a New American Century. “W” is in the midst of a perhaps inevitable popular rehabilitation these days; after all, compared to The Donald, Bush 43 seems like Thomas Frigging Jefferson, and he’s taken up painting, too, which is kind of sweet. Marble-mouthed, misinformed meathead though he surely was, at least he wasn’t totally nuts, right?

Well, no, but he was a rather witless tool of the forces that set the stage for the present woes, which have their roots in a style of Republican politics that stretches back decades prior to Trump’s ascendancy, all the way to Lee Atwater in the 1970s, and fellow travellers like Roger Ailes, Newt Gingrich, Roger Stone and Karl Rove, on through Presidents Nixon, Reagan, and to much different degrees, both Bushes. Theirs is the politics of white grievance and revanchism, of equating patriotism with militarism, of pitiless disdain for the poor and the weak, and ensuring the accumulation of the overwhelming preponderance of national wealth in the hands of the very few, while striving with tireless enthusiasm to get into wars, always wars, there can never be enough wars. They serve Mammon and worship at the temple of Mars.

In the early 2000s, it was the Dixie Chicks, pride of Texas, who unexpectedly found themselves up against the whole rah-rah, football loving, pickup driving, “USA! USA!” hollering axis that created, and was in turn nurtured by, the modern Republican Party. They seemed an unlikely set of culture warriors. In the late 90s they’d become the darlings of the country music scene, beloved by the sorts of beer drinking guys who pledged allegiance to Garth Brooks and Faith Hill, partly because they were really very talented, partly because their songs were catchy, and mainly, let’s face it, because they were, all three of them, quite beautiful. Anyone listening even a little attentively might have detected the feminist themes of songs like the massive hit Goodbye Earl, but most of their fan base was probably too busy tapping their toes and taking in the scenery to really notice.

It was clearly everyone’s assumption that the Dixie Chicks were the sort of nice, down home girls who were on the right side of the liberal-conservative divide, on their side, and it was thus an almost spasmodic, visceral reaction that greeted the effrontery – the horrible betrayal – with which lead singer Natalie Maines dissed beloved President Bush in front of a foreign audience in London, England. Voicing opposition to the Bush Administration’s bellicose policy toward Iraq, Maines, speaking from the heart to the Shepherd’s Bush crowd as invasion loomed, said:

Just so you know, we’re on the good side with y’all. We do not want this war, this violence, and we’re ashamed that the President of the United States is from Texas.

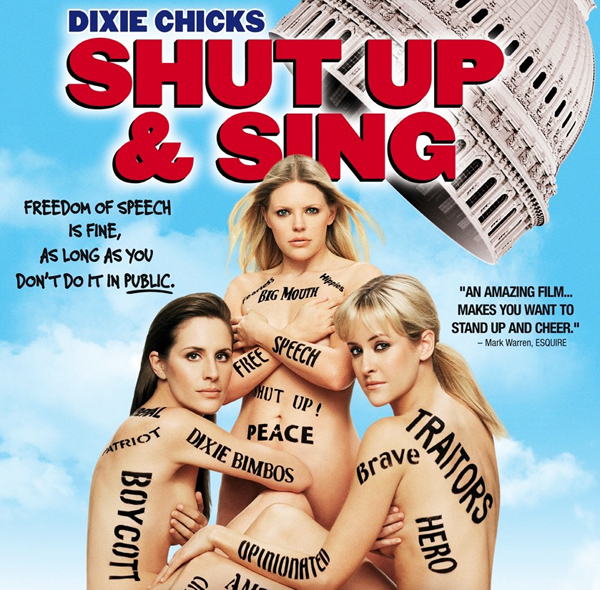

Christ! She had the gall to say that to a bunch of foreigners. It was practically treason! The backlash was swift and massive, akin to the reaction to John Lennon’s “bigger than Jesus” quip, except even more intense, complete with boycotts, record burnings, and patriotic radio stations throughout the US South refusing to play their music. There were protests, terrifyingly credible death threats, and so much general, appalling nastiness that it looked like the Dixie Chicks might be finished. The whole miserable affair, rendered all the more ugly by the pervasive drumbeat of threatened violence against uppity women who didn’t know their place, is chronicled in the emotional documentary Shut Up and Sing.

Not Ready to Make Nice is the musical distillation of the controversy, and the Chicks’ stirringly defiant declaration of unyielding principle. They would not bend. They were not sorry. They would not grovel, they would not forget, and y’all could go fuck y’all.

It’s a simply wonderful piece of work, surely their best, and the sort of song that any reputable artist would be satisfied to regard as the culmination of a career. In this remarkable clip from 2011, Maines just belts it out, with all the conviction and emotional honesty borne of rage, pain, and completely unaffected righteous indignation, undimmed despite the intervening years. The crescendo reached in the middle eight – they write me a letter/sayin’ that I better/shut up and sing or my life will be over – could move a lump of granite to goosebumps. You will never see a better live performance.

When the same yahoos who lashed out back then gnash their teeth at the NFL players who today take a knee, remember the Dixie Chicks, and the battle that needs always to be fought by decent people of conscience. The women were, after all, absolutely goddam right – the my-country-right-or-wrong buttheads who supported Bush and threatened to kill Maines would probably look down at their cowboy boots and mumble something incoherent if you asked them how they feel now about the horrendous blunder of Operation Iraqi Freedom. One day, no doubt, they’ll do the same when you try to get them to explain why they were so mindlessly hot and horny for Trump. Or more likely, the chickenshits will deny they ever supported the monster.

Meanwhile, somebody should make them watch these magnificent women sing their hearts out, and slap them upside their empty heads.

Song of the Day: Randy Newman – I Think it’s Going to Rain Today (September 24, 2018)

Randy Newman was always a man out of time, composing piano-driven, classically orchestrated character studies and social commentaries that have more to do with Stephen Foster than the blues/rock tradition that’s dominated all of popular music for the past 70 years or so. Though he’s been writing songs professionally since he was 17, and been covered by myriad artists over the years, he’s about as obscure as a successful genius can be, having spent a lifetime writing as if he knows nobody’s going to buy his stuff, but figures he may as well keep going anyway. By turns witty, sardonic, scathing, and sentimental, Newman crafts sophisticated pieces about real emotions and real human weaknesses, and invents characters that are sometimes truly distasteful yet somehow, in his portrayal, deeply sympathetic. People are complex, you see, their souls run through with contradictions, and sometimes they find themselves lost, lonely, and haunted by honest introspection that reveals themselves to be far less than they once hoped to be, and could well have been, maybe, if a few things had broken the other way. Newman writes about love lost, chances missed, character flaws that were never overcome, and the shame that often accompanies those moments when you can’t quite muster up the self-delusion that otherwise generally gets you through the day.

He can fool you, too, luring you in, all sweetness and light, until you realize you’re actually hip-deep in something awful. In Sail Away, you discover about half way through that the nice man delivering a group of immigrants to the promised land of America is a slave ship captain spinning tales to keep his human cargo duped and quiescent. In Marie, what starts out as a beautiful love song ends up being a confession of at best passive-aggressive spousal abuse. You’re the song that the trees sing when the wind blows, he tells her, a sentiment haunting and beautiful enough to grace an Elizabethan sonnet, before admitting:

Sometimes I’m crazy but I guess you know

I’m weak and I’m lazy and I hurt you so

And I don’t listen to a word you say

And when you’re in trouble I turn away

Yet you come away believing that he really does love this woman with all his heart, and deeply regrets that he can’t understand his own behaviour, or where his dark impulses come from. You can’t forgive this guy, but still he makes you sad.

So it goes in Newman world. His perspective can seem almost olympian, as he surveys the human condition from the standpoints of different generations and cultures, always conscious of the weight of the past, the events that led us down the twisty road to leave us standing here in the dog’s business. His experiences growing up in the corrupt political swamp of New Orleans loom large – he once wrote a whole song cycle, Good Old Boys, about the South of his youth and the political landscape dominated by Huey Long, which includes the epic recounting of one of the most massive floods in American history, Louisiana, 1927 – but over the years he’s trained his jaundiced eye on everything from the fatuous culture of sun-drenched L.A., to the cruelty of European imperialism in the age of empires and colonization, to the mind-set of the white minority governing Apartheid era South Africa. He criticizes, yes, he even makes fun, but you’re as likely to find him full of sympathy as contempt. Newman understands. He gets it, which isn’t the same thing as agreeing, or approving (though casual listeners have sometimes thought so), but he knows where the feelings come from, why the enraged ex-lover might dream of murdering the woman who left him in Bad News From Home, why the hard-hearted father might tell his son I Want You to Hurt Like I Do, or why the naive mind of a child could be over-awed by the sight of an essentially fascist, preening formation of motorcycle cops in Jolly Coppers on Parade. His songs can be about anybody, anywhere – who but Newman could write from the perspective of a pained and bitter angel, a dead Englishman, remembering all that was lost by his homeland during two World Wars? This is from Little Island, sung on record by Elton John:

In two long wars, my country bled

To spare the world the fearsome Hun

As through the years, the fight we’d led

Too long, we stood alone, too long alone

Little Island

And when at last, battle’s won

We asked for no reward and no reward was received

The empire gone

Two generations turned to blood and dust

Only the best were lost

Only the best…

Newman understands the ways in which history, culture and context shape the present, how attitudes are formed and patterns of behaviour come to be set by forces most of us don’t bother to think about. To him, life is mainly a series of tragedies, some we create, and some that were foisted upon us, and it’s hard to say who’s to blame, really. It all seems inevitable, and that’s the worst part.

By contrast to much of the rest of his best work, I think it’s Going to Rain Today, which was released on his very first album in 1968, is straightforward and in the moment. There isn’t a great deal to interpret, no narrative twist to figure out, no mystery to the back story. It’s merely popular music’s purest and most unblinking expression of loneliness, betrayal and depression. It begins with an almost cinematic mise en scène, broken windows, empty hallways, and a pale dead moon in a sky streaked with grey, before laying bare the lies that underpin feigned, feckless, purported human kindness, and the hopelessness of trusting anybody but yourself:

Lonely, lonely

Tin can at my feet

Think I’ll kick it down the street

That’s the way to treat a friend

It could have been written a century ago. Longer. They could have used it in a Greek tragedy.

Barely anybody noticed, at the time. Newman’s eponymous first record probably sold fewer than 5,000 copies, and of course never came close to the Billboard Hot 200. It was even out of print for about 15 years, beginning around 1980. There were some critics who praised the effort, and there might have been some solace in a congratulatory telegram that was sent, immediately upon the album’s release, by an English kid named McCartney, but other than that the thing sank without a bubble.

Oh well. In later years, Randy would earn serious coin writing soundtracks for movies, most notably for Pixar titles like Toy Story, so he wasn’t about to starve or anything. Meanwhile, if he wasn’t going to be top of the pops, he could at least stay true to himself, and such has its own rewards, right? Sure! Better to stay true to yourself and also be fabulously wealthy, though, is likely what Randy would say.

Song of the Day: Dobie Gray – Drift Away (October 17, 2018)

I carry on like a child of the Sixties, because those are the times with which I most closely identify, and I was there for some of it. I have some memories. But I was only nine in 1970, and my most crucial formative years were still before me when the Beatles broke up. The bitter truth of it is I’m actually a child of the Seventies.

Why bitter? Well, in the main, the Seventies sucked. They were years of maximum suckage. The Seventies are Watergate, the Energy Crisis, “stagflation”, the disastrous end of the Vietnam War, the Ford Pinto, platform shoes, and pop culture swirling ’round the bowl. Not all pop culture – for some reason, the movies of the Seventies were almost uniformly excellent, and often of a nature that could never be duplicated today, because they had the guts to eschew pat, happy endings – think Chinatown. It’s also true that there was great music in the Seventies, from the likes of Randy Newman, Paul Simon, Jackson Browne, and Joni Mitchell, and a trio from the pantheon of greatest rock albums ever made – Exile on Main Street, Who’s Next, and Every Picture Tells a Story – also belongs to the Seventies, albeit the early Seventies, which many think are more rightly thought of as the end of a decade that didn’t really begin in North America until February 1964.

Heck, Born to Run was the Seventies, wasn’t it? So was Walk on the Wild Side, and Night Moves. That was all great, but it wasn’t the zeitgeist. The zeitgeist was Laverne and Shirley, the Fonz going ayyyyyyyyyyy, and Charlie’s Angels. It was Disco Duck, Kung Fu Fighting, Convoy, and the Theme From the Poseidon Adventure. It was ChiPs. It was Disco. It was The Love Boat. It was harvest gold fridges, avacado green counter tops, and shag rugs in the wood-panelled rec room. It was rock as crazed Kabuki Theatre, with KISS. It was Glam, and bell-bottoms, and polyester. It was inauthentic, mass-produced crap. It sucked.

Not quite everything that made it big, though. Now and then a song managed to be both great and the consensus Top 40 radio favourite, and one of those was Dobie Gray’s Drift Away, released in 1973, though it was originally a country song written by one Mentor Williams and recorded by John Henry Kurtz, whoever that was, in 1972. It just goes to show you that music is music, and what starts out as a Country lament may yet contain the germ of Soul, because sad is sad, hurt is hurt, and we all experience our lives through a finite, universal repertoire of states of mind.

I don’t know anybody who doesn’t respond to Drift Away, which makes itself the subliminal soundtrack whenever I think back to my own wobbly adolescence as I lived through it in Grade 7, going to Gorsebrook School, in Halifax Nova Scotia. That was back in 1973. 1973. So very long ago, yet more fresh in my memory than, say, 2003. 1973 was the year on the cusp for me, when everything was changing and about to change more, the year when I bought the Blue Album and became a dyed-in-the-wool Beatles fan, the year I started to think critically, really think, the year I first realized there was a future I was running towards and had no idea what it would be like, the year I first fell in love with a girl who was too beautiful to be attainable, yet almost an honest-to-God girlfriend, for just a couple of weeks during an almost dreamlike October.

Funny how you only remember school when it was Autumn.

Anyway, that’s Drift Away to me, and I suspect it tugs on one or another heart string of just about everybody who was there when it first came out. It seems to have been designed for just that purpose, to freeze a time and a place in your mind’s eye, and provide a wistful score for the elegy you’re one day sure to write.

Song of the Day: Jackson Browne – The Load Out (October 17, 2018)

Writing about Dobie Gray and the Seventies just now sent me back to the time my brother Mark brought home what may be the greatest road album ever made, Jackson Browne’s Running on Empty. The record was part live stadium performances, part impromptu demos made on the tour bus, and ends with the most perfect song imaginable to close out a concert: The Load Out, a thoughtful, wistful, highly melodic take on the conflicted emotions a performer experiences once the show’s over. It’s almost a sober version of the Velvet Underground’s Sunday Morning, which was about coming down from the drug-induced high of Saturday night; here, Browne sings about coming down from the high of a successful concert, having basked for a moment in that massive burst of approving energy that comes from an arena full of fans, only to be left there feeling, after it’s over, like the way Sissy Spacek’s character described it in Badlands, as if you’re sitting in a bathtub and all the water’s run out. These lines always leave me blubbering like a baby:

Tonight the people were so fine

They waited there in line

And when they got up on their feet they made the show

And that was sweet…

But now I hear the sound

Of slamming doors and folding chairs

And that’s a sound they’ll never know

The bangs and squeaks of slamming doors and folding chairs echoing through the empty arena as the roadies pack it all away, as lonely as the sound of a train in the distance at three in the morning. Then there’s these:

But the band’s on the bus

And they’re waiting to go

We’ve got to drive all night and do a show in Chicago

or Detroit, I don’t know

We do so many shows in a row

And these towns all look the same

Yeah, there’s romance to being on tour on the open road, but there’s also heartache, let-down, and the realization that every moment of exaltation is fleeting – though oh, how magical when it all comes together, and the energy of the fans lifts the band higher. Those are the memories that keep you going during the endless hours on the road between gigs, waiting to arrive at the next nondescript motel, missing home, and maybe thinking about a time to come when there will be no more tours, no more crowds eager to shell out just to hear you in person.

These words could surely serve as the plea of every band that ever toured:

People you’ve got the power over what we do

You can sit there and wait

Or you can pull us through

Come along, sing the song

You know you can’t go wrong

‘Cause when that morning sun comes beating down

You’re going to wake up in your town

But we’ll be scheduled to appear

A thousand miles away from here