Song of the Day: The Beatles – Penny Lane (December 6, 2018)

This is the text of an e-mail I fired back to a co-worker on a day when the papers reported the death of David Mason, the baroque trumpeter of the London Philharmonic, who famously lent his piccolo trumpet to Penny Lane. She attached a link and asked if I’d seen the item.

I decided I rather liked my missive, and kept it. So this is my response, written in 2012.

Yes – this article is actually nicer than the one that appeared in the print version this morning, which was headlined “The Guy Who Played Trumpet on Penny Lane has Died”, and went on to dismissively equate Mason with various oddball celebrities who were famous for only one silly little thing, trifles like the “peppy little riff” of trumpet that “launches” Penny Lane (the trumpet of course appears first in the middle, and doesn’t launch the song at all).

Made me quite angry, actually! “The Guy” indeed. Sets me off on one of my rants.

Penny Lane has always had an extra special place in my heart – it was the first song I ever loved, as a six year old, listening to its graceful melody wafting out of innumerable open windows and car radios along the streets where I lived, which in memory are always bathed in sunshine (a phenomenon that happens to be the theme of the song). It remains my favourite, 45 years on, and I’m always dismayed when people underrate it. It’s usually described as cheerful and upbeat, which it is on the surface, but as with so many McCartney compositions of the period (like the gorgeous Mother Nature’s Son off the White Album), it contains nuance that hints at layers of yearning and sadness underneath, and also a doubting self-awareness, exemplified by the chord changes that occur in the middle of every verse (on the last word – “know” – before “and all the people that come and go”, on the word “back” just before “and the banker never wears a Mac”, and so on.) It has a quizzical feel to it, a hint that the singer suspects something isn’t quite right about this mental image of the Penny Lane of his youth, even though the song immediately snaps back into the dominant chord of the verse, and that nagging feeling is quickly set aside. Watch this:

And indeed, something is amiss. Author Ian Macdonald sensed a part of this in commenting that the song is “as sly and knowing as a group of mischievous and observant kids straggling home from school”, and there is that element of bemused mockery, but in the service of a much bigger idea – for Penny Lane is about the frailty of memory, and the sad awareness that the way one remembers things, all blue skies and happy goings-on, is not really the way things were. Thus the pretty nurse, dressed up and selling poppies for Remembrance Day, not only has a self-conscious feeling that she’s in a play – she is anyway, just another archetypal character in the pleasant fiction. The Penny Lane that today fills his ears and eyes never really existed, and the narrator knows it. That’s just the way nostalgia works, and even if it wasn’t quite like this, wouldn’t it have been wonderful if it was? Who says you can’t miss something that never was? Penny Lane implies that all of us probably do.

Musically, the song is deceptively and dazzlingly complex, beginning not with trumpet, but a flourish of bass guitar, which sets up a marvellous contrapuntal “walking” bass line, loping along in almost jaunty fashion. Like nearly all McCartney bass lines, this one is tuneful and ingenious, crucial to the song’s harmonic structure. In Paul’s hands, the bass sings a song all its own, and much of the joy to be had in repeated listens of Penny Lane is in the way it intertwines the separate melodies of the bass and vocal lines. Also magical is that the chorus is in a different key to the verse, the song hopping from B to A, with A representing the current reality, and B the distant memory, until the very end, when a modulation brings the chorus into B.

This is expert songwriting.

Apart from the piccolo trumpet, the arrangement boasts a conventional horn section, flutes, a fire bell, and a droning upright double bass that highlights the banker settling in to the barber’s chair for his trim. Of greatest note is the uncanny staccato piano sound that anchors the verses, the product of an arduous recording process that made the most of the four track tape technology then available. No single piano produced the timbre that Paul heard in his head, so he kept layering piano on top of piano on the master tape, until it ‘s not a single instrument, but four playing in unison, some at accelerated pitch, with added hints of percussion (bells, or some sort of xylophone perhaps?) to supply finishing touches. Both Lennon and George Martin contributed overdubs to this uber-piano, creating an effect that is at once indefinable yet perfectly natural; the listener doesn’t know why, but it just sounds right. This is perhaps best heard after the exclamation about the nurse, that “she is anyway” – Ian MacDonald again supplies the apt turn of phrase, referring to this moment as a “shivering ecstasy of grace notes”. There is nothing quite like it in any other recording.

All the elements come together in the final verse, the piccolo trumpet, the flutes, the horns, the super-piano – here we turn to author Jonathan Gould for the evocative image of the “toy trumpet and penny whistles snapping like pennants in the wind” as the final modulation leads to an abrupt and almost disconcerting conclusion. The song just ends. There is a sudden shimmering flourish of close-miked cymbal, leading the listener to experience a sort of aural representation of the reverie ending, almost literally the sound of an illusion dissolving, and as the narrator exclaims one last longing “Penny Lane!” the moment simply passes. It’s almost like somebody has yelled “Snap out of it!” at the day-dreaming singer. Someone once commented that Penny Lane doesn’t so much conclude as hit a wall and ricochet, which I’ve always thought is a good way to put it, yet this doesn’t quite capture the underlying melancholy, the sense of loss. Those who decry McCartney’s shallow good cheer seem never to sense the tears that so often lie just beneath the laughter.

In the initial mix, Mason plays one last plaintive trumpet riff over the cymbals, but this was gilding the lily, and it was removed after a first pressing of singles was sent out for airplay. You can hear the original on one of the Anthology discs, and the decision to remove the trumpet coda can be heard to make perfect sense. While pleasing, it’s an ornament that dilutes the finality.

To top it all off is a vocal performance of piercing clarity, typically free of even a hint of tremor or strain. That high-pitched flute-like sound that provides counterpoint to the piccolo trumpet solo in mid-song is McCartney’s own voice. Bob Dylan has said that there never was singer better than McCartney is, or Lennon was, and this is an aspect of their work that is often overlooked, as if it’s just too much that they should have been gifted that way too.

All that subtlety and complexity, yet you can sing it in the shower – the mark of a truly great song. To me, there never has been one better. Yet when Rolling Stone set out to rank the 500 greatest songs of all time, they placed Penny Lane at #449. Four hundred and forty-ninth. Rolling Stone thinks that there are four hundred and forty-eight songs that are better than Penny Lane!! It’s depressing to be reminded how few can really appreciate music; even in rankings of Beatle songs, Penny Lane often arrives somewhere in the middle of the pack, characterized as the acme of good cheer and a typically McCartneyesque counterpoint to the inappropriately more highly rated Strawberry Fields Forever, the flip-side to Penny Lane on what George Martin calls the greatest single ever made. It’s a pretty good litmus test, actually. If you think Penny Lane is a simple and relentlessly cheerful little ditty, you have a tin ear, limited imagination, and quite possibly no soul.

Penny Lane resides on a rarefied plateau alongside the best of Gershwin, Porter and Rogers. It is surely one of the greatest popular songs ever written. So for me it’s really quite sad that “the guy who played trumpet” is no longer with us. David Mason’s contribution is the final touch that elevated Penny Lane into supernatural territory, and I hope it seemed to him that the fame he earned from his afternoon’s work at Abbey Road studios was well deserved. To think he might never have been recruited had McCartney not happened upon Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 on the television one evening, seen Mason play, and realized that’s the sound I need.

Song of the Day: The Tragically Hip – Nautical Disaster (December 8, 2018)

A powerful, hard-rocking recounting of a nightmare, or perhaps a vision, performed by a band that knows far more about history than any group of (then) young rockers should. I think it’s the best of this quintessentially Canadian group’s output, and it still seems quite recent to me, though horrifyingly, it’s now well over 20 years old. It’s about something that happened in 1940, and there’s no reason for you to have ever heard of the event, nor any way that researching the inspiration for this song will help you to find out, since if you look it up you’ll find people (including, amazingly, beloved and sadly departed band member Gord Downie himself) saying it’s about the sinking of the German battleship Bismarck. Yet it simply can’t be, the historical facts don’t even remotely fit the narrative, and more than that, the narrative does fit perfectly a disaster that indeed happened just off the coast of France within sight of a rocky shore (Bismarck was well out to sea when sunk), and the lighthouse at St. Nazaire.

In 1940, the Germans overran France with a speed and facility that was, at the time, stunning. The Germans called it “lightning war”, Blitzkreig – we call it “maneuver warfare” today, and it’s now the manner in which all highly mobile armoured forces, accompanied by mechanized infantry and supported by air power, go about their grim business. As the vice tightened, Allied forces scrambled to abandon the Continent, and while many are familiar with the events at Dunkirk, especially following Chris Nolan’s epic movie, lost to the public consciousness is the sinking of RMS Lancastria, a singular tragedy amidst the general withdrawal of British forces from France in the teeth of the Nazi onslaught.

The Lancastria (reclassified in military service as “HMT” for “Hired Military Transport”) was part of an ongoing effort to evacuate British personnel and civilians under Operation Ariel, which continued for weeks after the Dunkirk sealift. Her ordinary capacity was about 1,300 passengers, but in the emergency she was loaded up with many thousands more, providing a fat target for the merciless German warplanes that sank her. It’s a common estimate that about 4,000 men drowned at a stroke (twice the crew of any battleship, including Bismarck, which had a complement of 2,065). Some sources claim over 5,000, even 6,000 – a huge mass of people going into the water off the coast of France, metaphorically in the pocket of a lighthouse sitting amid jagged rocks on the shoreline. It was the largest nautical disaster in British maritime history.

You can read about it here:

:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RMS_Lancastria

Really, what else could these lyrics be about?

I had this dream

where I relished the fray

and the screaming

filled my head all day.

It was as though

I’d been spit here,

settled in, into the pocket

of a lighthouse

on some rocky socket,

off the coast of France, dear.

One afternoon, four thousand men

died in the water here

and five hundred more were

thrashing madly

as parasites might

in your blood

This group has other songs similarly evocative of World War II, like Scared, with its imagery of damaged destroyers limping into the bay, and 50 Mission Cap, ostensibly about the last time the Leafs won the Stanley Cup, which repeats a phrase that evokes a cherished rite of passage for U.S. combat pilots – when their cap became so grizzled, stained and crumpled that it was said to have a “50 mission crush” to it, the mark of a wily veteran.

I’ve always been struck by the extent to which Nautical Disaster bears an unlikely, and I suspect quite deliberate, structural resemblance to Coleridge’s famous Kubla Khan. The poem was composed while the author was in the midst of what was probably an opium-induced reverie, experiencing visions that he was busily committing to paper, when his trance was interrupted by a sudden knock on the door (described as a “person on business from Porlock”), whose arrival hauled Coleridge back down to earth. By the time the fellow from Porlock had been dealt with, the visions had vanished – probably, the poet was sobering up – and to Coleridge’s great regret he couldn’t get them back. Thus the abrupt change of voice for the poem’s concluding stanza, which begins “A damsel with a dulcimer in a vision once I saw”. Sadly, what he’d seen in his mind’s eye was now nothing more than a fading memory. Nautical Disaster follows the same pattern: a feverish vision within a dream state, and then the sudden interruption – not a knock on the door this time, but the phone ringing – which brings the reverie to an abrupt end, leaving only the faint but lingering memory of the dream behind after the mundane, “hi, how you doin’” conversation is over. As far as I’m aware, nobody else has ever perceived it, but to me the parallel seems too exact for mere coincidence.

Since the very first time I heard this song, thoughts of lifeboats designed for 10 men, and 10 only, and paddling away from drowning comrades to the sound of fingernails scratching on the hull, have never lost their capacity to haunt.

Song of the Day: Randy Newman – Louisiana, 1927 (December 13, 2008)

In 1927 a horrible flood of the Mississippi, the product of almost Biblical sustained rainfall, drove over 700,000 people out of their homes in Louisiana. Newman commemorated the event as part of a song cycle of the South called Good Old Boys, which was released in 1974. I discovered it around 1980 or so, and it quickly became, and has remained, my favourite of all of his songs – and he’s written some incredible songs.

The tragedy is narrated in a dry, fatalistic fashion that only adds to the poignancy: Some people got lost in the flood. Some people got away all right. That’s just how luck breaks, you know? Its mournful refrain, “They’re tryin’ to wash us away”, evokes that very human intuition that a calamity of this size can’t just be the product of dumb luck, no, it must be part of some deliberate plan to wipe you off the face of the earth; this just has to be somebody’s doing, there just has to be someone to blame. And indeed, to a certain extent for some, yes, because some of the flooding was the result of dynamiting levees, in order to relieve the pressure and spare New Orleans, deliberately sacrificing smaller communities upstream. It didn’t help.

In the wake of Hurricane Katrina, this song seemed almost prophetic. When George Bush flew over to observe the devastation from the comfort of Air Force One, you can bet the lines about the President’s visit in 1927 leapt to mind.*

This was, almost inevitably, the first song performed at the 2005 benefit concert for the victims of Katrina, and it’s since become a sort of anthem to memorialize that eerily similar fiasco. It was a powerful thing even before the levees broke and the Lower Ninth all but vanished underwater. These days, I’ve read, it brings crowds down there to tears.

I recently discovered this chorale, which gives more overt expression to the song’s underlying emotions:

Song of the Day: Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas – Trains and Boats and Planes (December 19, 2018)

The first time I heard this song I was a kid in the mid-1960s, I’m not sure what year, maybe 1967 or so, which would have made me six or seven years old. It’s one of those snippets of memory that jumps out of the general haze; you can’t remember what year it was, how old you were, or much of anything else that might have happened that whole year, but this one moment is frozen with complete clarity in your mind’s eye.

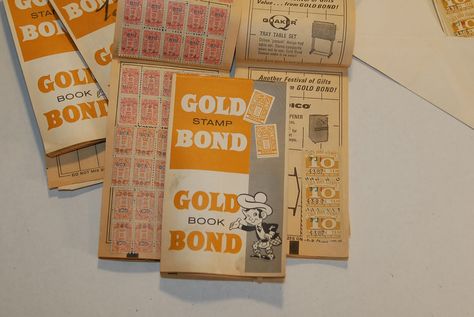

It was a dark winter evening, and I was sitting next to my Mom in the front seat of the car, waiting for a grocery store employee to load our purchases into the trunk. That was the norm back then, the cashier handed you a numbered chit, and you drove around to collect the brown paper bags, which came out of the store in plastic crates on a roller system. Why do it yourself, when the kid can do it? The bins were made of red plastic. I had to push myself up in the seat to see them out the side window. My main perspective from my low perch on the big bench seat in the car was almost straight up through the windshield, looking at some fluorescent lights, and I’m pretty sure we were at one of the IGA chain of stores, because I remember my favourite part of going with Mom to get groceries was getting the little stamps that IGA handed you with each purchase, about the same size as postage stamps, which you licked and stuck into a booklet in a sort of Stone Age version of collecting Air Miles. They called them “Gold Bond Stamps”. It would have been a Thursday – Thursday was grocery day. I even remember the car, or think I do, a dark green Ford Custom, (maybe Custom 500?), which was a classic mid-60s sedan, and might have been one from the 1967 model year. In the dash, glowing a sort of yellow-orange, was one of those AM radios that had the big analog silver buttons under the dial, which you pushed in with a “clunk” to arrive at one of the four or five available pre-set channels. As you pushed one of them in, the one last selected would pop back out. I liked that feature especially. The radio itself sounded awful, I now know, but it was just fine back then. I can still hear the chirpy musical station identifier: “92 C-J-C-H!”

Billy J Kramer’s lovely version of Bacharach’s Trains and Boats and Planes, attached above, was playing on the radio. That’s why I remember the whole tableaux. It was one of the first times I found myself fully enthralled with a melody, which was one of Bacharach’s finest, and the idea of trains, boats, and planes appealed to my young mind – I thought it was a sort of ode to transportation, not a pining love song. Little boys think a lot about machines, especially the bigger ones that move. The song is unconventional for its era, in that it has a bridge, but no chorus, just verses. I think. The farther I go with this Songs of the Day series, the more it seems to me that it’d be better if I knew even the first thing about music theory.

Hal David’s lyrics are typically crisp and emotive:

We were so in love

and high above

we had a star to wish upon

wish, and dreams come true

but not for me

the trains and the boats and planes

took you away, away from me

It’s as if the deflated, lovesick narrator ascribes the motive to the vehicles, not the girl who left him, and thinks maybe some day they’ll decide to bring her back, if only his prayer can cross the sea for them to hear.

In the popular consciousness, Bacharach is not usually put in the pantheon with Lennon, McCartney, and Dylan, but I doubt that professional musicians and songwriters rate him as any less accomplished. His melodies are too sharp, the chords and time signatures too clever and unconventional, for him to be anything but one of the greatest songwriters of the 20th Century. He wasn’t topical, and sure wasn’t about to write Blowin’ in the Wind, or A Day in the Life, but sometimes you aren’t really up for contemplating modern alienation and media-saturated apathy, or railing against the depredations of The Man. Sometimes you just need to hear a sad, beautiful love song.

Song of the Day: Songs For a Christmas Eve (December 22, 2018)

Having re-posted my screed against that miserable, misanthropic saga of the egregiously abused reindeer Rudolf, and against Christmas jingles generally, for that matter, I thought it appropriate to balance the books here with some songs that Kathy and I always play on Christmas Eve. We usually cue these up to listen to while munching the best hors d’oeuvres ever conceived, water chestnuts soaked in a soy/brown sugar mix and then baked, wrapped in bacon. Oh, yum.

Our Christmas Eve playlist:

Vince Guaraldi Trio: Skating; Linus & Lucy

Surely the best thing about A Charlie Brown Christmas, which those of us of a certain age have probably seen at least fifty or sixty times, was the marvellous soundtrack supplied by the Vince Guaraldi Trio. Just the first few piano notes of Skating make me almost melt with nostalgia for the time when I was a kid on Christmas Eve. This cool, sophisticated Jazz was no mere cartoon accompaniment. You could keep hearing it, year after year, and still always love it, no matter how widely and wildly your tastes in music had expanded. It’s simply perfect, and the way it manages to be instantly appealing to almost everyone who hears it, however young, almost amounts to a public service. Probably nothing ever did more to educate the average North American child’s ear to the nuances of sophisticated musical construction, save perhaps the marvellous, often classically-inspired, background scores that the great Carl Stalling supplied for the legendary Looney Tunes of the 1940s and 50s. Which, now I think of it, may rate a blog post too, sometime.

Robert Downey Jr.: River

Yes, this is that Robert Downey Jr., and no, amazingly, it’s not a joke. Turns out the boy can sing. This was recorded for an album after first being played by Downey in an episode of the 90s yuppie quirk-fest Ally McBeal, one of those David Kelly TV shows that you either loved or despised. I didn’t watch it much after its first season, but was vaguely aware of the buzz surrounding the risky decision to hire Downey as a regular, a move meant to boost flagging ratings near the end of the show’s run. Risky, because at that point, the future Iron Man mega-star was a drug-addled wreck, unreliable, constantly in and out of rehab, always up on charges, and thoroughly on the outs in Hollywood. The closest recent equivalent would be Charlie Sheen, but there was one huge difference, and you can hear it in this performance. At the peak of his dysfunction, Charlie was an angry, arrogant, self-satisfied A-hole, mean and hurtful to everyone he touched. Downey wasn’t mean. He was just terribly, terribly sad. I think that’s why everyone was always willing to give him another shot.

The song, of course, is by Joni Mitchell, and appears on her landmark 1971 album Blue. A true Canadian, she found herself a young woman alone, disoriented and depressed, in L.A. one Christmas, which didn’t feel much like Christmas at all in the endless California summer, despite all the cardboard cut-out reindeer. Somehow, she was able to re-imagine the witlessly cheerful Jingle Bells, with which the song opens and closes, as a mournful refrain expressive of loss, guilt, and homesick longing. No snow and sleigh bells around here, no frozen river to skate away on.

I especially like River because it’s a break-up song that’s too self-aware to be about feeling hard done-by and wondering what went wrong. No, by her own account she brought this on herself, she was selfish, difficult, and threw away her chance at love. I doubt there’s ever been a more authentic expression of heartsick regret than her delivery of the simple lyric I made my baby cry.

Here’s Joni, if you prefer:

The Pretenders: 2000 Miles

Just about everybody responds to this lilting tale of Christmas homecoming, given voice by someone authentic enough to pull off raw sentiment, strings and all, without sounding sappy. This is a very nice live performance, which I find superior to the studio version.

Pogues: Fairy Tale of New York

I’ve often heard this sad, not at all syrupy lament described as the best Christmas song ever recorded. I suspect, perhaps, that not everyone would feel that way about this reminiscence of the Irish immigrant experience in America, as sung from the floor of the drunk tank, which provides an unflinching look back at all the crushed hopes born of the arrival in the New World, all of them amounting in the end to nothing but bitterness, recrimination, and bickering. The young lovers who hit New York back in the day, so full of anticipation, are now pretty much at each other’s throats.

You could argue this isn’t a Christmas song at all. It sure as shit ain’t Jingle Bells, let’s put it that way. This is a story of failure. I could have been someone, he pleads, and her answer is as cutting as it is true: Well, so could anyone. There’s something about the chorus that rings so true as a memory of years gone by, it’s somehow such an authentic little detail, that I almost feel like I was there myself, walking the streets of Manhattan in the era of Sinatra, when the whole world might have seemed to a newcomer to be there for the taking:

The boys of the NYPD choir

Were singing “Galway Bay”

And the bells were ringing out

For Christmas day

Gets me every time.

Sufjan Stevens: Only at Christmastime

A pretty little thing that grows on you. Superficially about the unique joys of Christmas, goodwill toward all, peace, love, and all that, I discern in this one a Randy Newman-like level of irony, an undercurrent of yeah, right that speaks to the empty promise and false gaity of a time of year that drives so many to suicide. Maybe that’s just me.

Gordon Lightfoot: Song for a Winter’s Night

Not really about Christmas, and actually, I heard Gordon recount one time how he wrote it on a rainy summer afternoon in a motel room in Detroit. Still, was anything ever more evocative of a quiet Christmas Eve, snuggling in front of the fire, as a thick blanket of snow accumulates on the dimly-lit streets outside?

Skydiggers: Good King Wenceslas

Christmas Eve just wouldn’t be the same without the Skydiggers’ rendition of this beautiful song.

In my youth, I always imagined this piece to have been written at some time nearly contemporaneous with the reign of the actual King Wenceslas. Not so. It was composed relatively recently, in 1853, by John Mason Neale and Thomas Helmore.

The real Wenceslas wasn’t even a King, technically, but a Bohemian Duke who reigned in the 10th Century, around whose life a myth of just and merciful rule was fostered by those promoting the concept of a righteous King, a rex iustus, whose divine right to authority was a function of his piety and his heartfelt adherence to Christian values – in other words, his worthiness to govern. This was not such a long way removed from the idea of governance that much later gained currency among the philosophers of the Enlightenment, that a Sovereign derived the right to rule from the consent of the people, which had to be earned, and could thus be revoked. There’s an almost straight line to be drawn from the ideal of Wenceslas to the ideas that much later gave impetus to the American Revolution.

In this interpretation of the classic Yuletide song, the Skydiggers manage to remain true to the original while effecting an extraordinary musical rejuvenation. If you want to get into the spirit of the Christian ideals that so often seem forgotten in the organized practice of Christianity, this is the thing. You may find yourself, as I did, really listening to the words for the first time, and finding hope in its sorely needed message of decency and kindness.

The arrangement is both moving and understated. The trumpet accompaniment in particular is sublime, and a little mournful, perhaps bringing to mind all those who still, in our own supposedly more enlightened time, never benefit from the sort of charity offered to this poor peasant by his humane and caring monarch, that stormy night of the second day of Christmas, over a thousand years past.