From 1924 to 1961, a wise and decent man, idiosyncratically and rather charmingly named Learned Hand, served as a federal appellate judge on New York’s Second Circuit. He never made it to the Supreme Court (a pity), so few in the lay public will have heard of him these days, but those of us who’ve been through law school, even Canadian law school, will have learned at least a little bit about him. He was one of those judges, like Cardozo, or Holmes, who was as much a philosopher as a lawyer, and dedicated his life to the pursuit not merely of sound legal outcomes, but of natural Justice, as best as he could comprehend, from circumstance to circumstance, which rulings came closest to achieving it. He wasn’t always sure. That was, I’ve read, his signal character trait; his was that rarest of minds which understood that any person, himself included, could be absolutely certain, yet absolutely wrong. His approach to wielding power over other peoples’ lives was imbued with self-questioning humility.

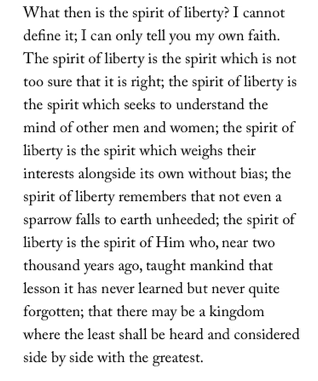

He was also a brilliant writer and orator, as I was reminded today, while surfing the web, when whatever I was searching for led me, somehow, to an article in the New Yorker. It discussed a speech given by Hand in 1944, just a couple of weeks before D-Day, after leading a huge assembly in New York’s Central Park, a crowd of fully 150,000 newly naturalized citizens, in the Pledge of Allegiance. In welcoming them to the enjoyment of the privileges of American citizenship, he sought to explain to them what it meant to be free, and how true freedom in civil society implied more than just the exercise of one’s own rights. There also needed to be some sense of responsibility for the preservation of those same rights for everybody else. There needed to be mutual respect, and a mutual grant of leeway. He spoke about the “spirit of liberty”:

This, I’d argue, is eloquence on a par with the Gettysburg Address, and it’s also the most humane articulation I’ve yet encountered of the intellectual and behavioural underpinnings of free and peaceful coexistence in an open society. His evocation of the teachings of Christ (despite being, himself, an agnostic), and his reminder that people should govern themselves in light of the belief that we might all, one day, find ourselves judged on an equal footing with those we might now consider our inferiors, reminds me of the philosopher John Rawls, whose Theory of Justice was part of my curriculum in university. Rawls believed that those with the power to make law should do so as if they were blinded to their present circumstances by a “veil of ignorance” that prevented them from knowing their own station in life. They should imagine that having imposed the rules, they might then emerge through that veil to find themselves wealthy or poor, clever or dim, free or imprisoned, male or female, the happy descendants of plutocrats or the miserable children of the downtrodden; in that case, would the policies they just buttressed with the coercive power of the state still seem fair and just to them, no matter who they turned out to be? Twenty-seven years earlier, Hand was saying something spiritually similar that led to the same results: that one day, any power and privilege we now enjoy may weigh nothing in the balance, and that it was best, in that case, to pursue justice over raw advantage.

Even more moving and relevant in today’s context, to these ears anyway, is the statement that “the spirit of liberty is the spirit which is not too sure it is right”. How little we see of that spirit today, and how much better off we’d be if this was a notion that most people adopted as a guiding principle. Absolute certainty is an essential element of systemic cruelty and tyranny, and a hallmark of the beliefs of those who would, today, deport immigrants, put all manner of criminals to death, deny women reproductive autonomy, prevent certain segments of the population from having any say in their own governance, deprive the poor, the weak, and the sick of the support of greater society, and put all political power in the self-selected hands of a very few. In this fraught moment, with democracy teetering on the brink in America, and populist extremism gaining adherents throughout the Western, liberal democratic world, we’re continuously assailed by the shrill, shouting voices of those who’ve never once doubted their own world view. Some of them believe they understand the mind of God. Some of them are sure that only certain people, those, not coincidentally, exactly like themselves, should have anything to do with ruling over the masses. Some of them are convinced that empathy, compassion, and charity are vices that unfairly penalize the successful to the benefit of those who deserved to lose. All are absolutely convinced of the merits of their own beliefs, and willing to inflict almost any amount of pain and punishment upon those who don’t agree. Only they, after all, know the truth.

I’ve grown to believe, over the years, as I edge towards my inevitable decrepitude, that the main thing I’ve learned from my many years of experience and ongoing inquiry is that I haven’t learned enough. The only thing I really know is that I don’t really know. Oh, I still have my fixed ideas, and certain more or less fixed principles, but in these latter years there aren’t so many, and they tend towards vague and perhaps soft-headed, sappy, vaguely utilitarian notions, such as “anything that increases the sum total of human misery is probably a bad thing”. Fine, but how do you calculate human misery? Whose misery matters more, or does no-one’s? How can you be sure, when you get down to the brass tacks of governing, which policy prescriptions make people less rather than more miserable? Does the ecstatic joy of the many outweigh the abject despair of the few? What if the right thing seems to make everybody miserable, at least in the short run? Is public policy purely the art of making everybody as happy as possible, or is it also, sometimes, properly akin to making a child eat his vegetables? Is paternalism always arrogance? Who decides?

I don’t know. Overarching principles are all well and good, but God is in the details. So we try, we see, we change tack as necessary, we listen to the aggrieved and the dissenters, and we muddle through, trying to hew to our core beliefs while straining to keep our minds open at the same time – right? Don’t we? Or, at least, shouldn’t we?

The spirit of liberty is the one which is not too sure it is right. Now it seems like a dangerous and growing coalition of very angry people doesn’t hardly see it that way. Maybe that’s why my side is losing. We feel doubt and they don’t. We hesitate when they act without thinking. Yet still, I don’t want to win it their way. I’m not saying that circumstances aren’t becoming dire enough to push me into fighting fire with fire, but what I really want, which I grant may be impossible if too many others don’t, is to live by the beautiful words of the great Learned Hand.

This is a beautiful piece of writing. “Maybe that’s why my side is losing. We feel doubt and they don’t. We hesitate when they act without thinking”: You (and Hand) have both somehow articulated exactly what wakes me up in the middle of the night.

LikeLike

Jillian, this comment means so much to me. Your opinion means so much to me. Thank you, from the bottom of my heart.

LikeLike

Oh, and also, don’t abandon all hope. I’m not going to. Neither should you. Promise. This pendulum swings both ways.

LikeLike

excellent-wholly agree! thank you. Best regards, Holly Anderson

>

LikeLike